Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Astronomers are watching an exoplanet slowly fall into its star

This time, when the world ends, it's for real.

In Lorene Scafaria’s 2012 apocalyptic rom-com Seeking a Friend for the End of the World (now streaming on Peacock!), Dodge Peterson (Steve Carell) and Penelope Lockhart (Keira Knightly) spark up an unexpected friendship under the literal and looming shadow of an oncoming asteroid. After a failed attempt to destroy the asteroid called “Matilda,” humanity is left with three weeks to consider their inevitable demise and nothing to do but wait for the world to end.

The thing is, the world isn’t going to end. Not really. Even if a killer asteroid found its way to Earth for a repeat beating, the planet would survive. It’s even likely that life would continue on without us, as it has done several times before. It wouldn’t be the end of the world, just the end of us. Which can feel like the same thing.

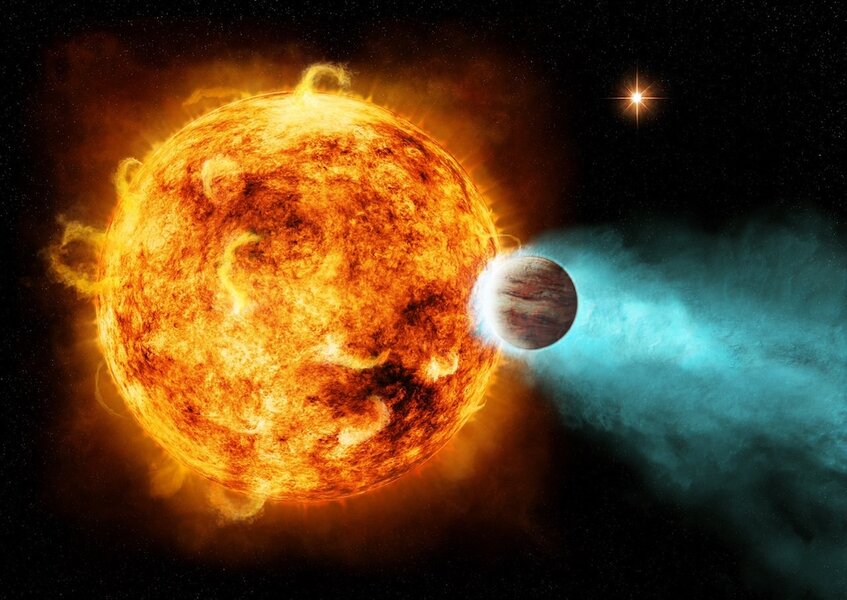

Elsewhere in the universe, however, worlds really are ending, and astronomers have a front row seat to a distant apocalypse in progress. More than 2,000 light years from here, our telescopes have set their sights on a star called Kepler-1658. It’s about one and a half times the mass of the Sun, almost three times the size, and it’s patiently waiting to swallow one of its planets whole. That’s according to a new paper published in The Astrophysical Journal.

That planet, dubbed Kepler-1658b, was first detected by the Kepler Space Telescope in 2009. In fact, it was one of the first exoplanets to be identified and it’s practically the poster child for Hot Jupiters. That’s the name for massive gas giants with orbits unusually close to their parent stars. Many are several times the mass of Jupiter with orbits so close in they’re almost kissing. The romantic and gravitational tension is fierce.

Hot Jupiters are disproportionately represented among confirmed exoplanets because they are among the easiest to find. One of the most common methods of exoplanet detection is the transit method, in which astronomers pick up on minute decreases in a star’s brightness when a planet passes in front of it. Large planets with close orbits necessarily block a comparatively large slice of light, making them easier to find. Hot Jupiters stick out.

RELATED: Astronomers find a torched super-Earth one a ONE DAY orbit around its star

In the case of Kepler-1658b, the close orbit offers astronomers an additional benefit. Planets closer to their stars tend to have shorter orbital periods than those farther out, a consequence of the way gravity tugs on objects differently depending on how far away they are. A shorter orbital period means Kepler-1658b passes in front of its star relatively often, roughly every four Earth days. Astronomers have been watching 1658b for about 13 years, giving them a considerable amount of data about the evolution of the planet’s orbit. That data recently revealed a tragic discovery: Kepler-1658b is slowly falling into its star and is doomed to be entirely consumed.

Over the last 13 years, measurements taken first by the Kepler Space Telescope and later by the Palomar Observatory’s Hale Telescope and NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Telescope have documented a steady degradation of the planet’s orbit. With every passing (Earth) year, 1658b’s orbit gets a little bit shorter and a little bit closer in. Observations have confirmed the orbital distance has diminished an average of 131 milliseconds every year.

Researchers believe the orbital decay is caused by tidal interactions between the planet and the star, similar to the relationship between the Earth and the Moon. In our case, the Moon is slowly slipping our grasp and creeping a little further into the cosmic darkness with every revolution. Kepler-1658b has the opposite problem. Every year, 131 seconds get shaved off its orbit, and it inches a little closer to its parent star. At its current rate of degradation, it should spiral into the star some time in the next two and a half million years. That’s relatively quickly, astronomically speaking.

In the meantime, astronomers plan to continue studying Kepler-1658b and hopefully find more exoplanets like it, so we can better understand the way mature stellar systems behave.

On long enough timescales, the end comes for us all, but you can up your chances of survival with Bill Nye’s The End is Nye, streaming now on Peacock!