Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Mmmmm, donut illusion

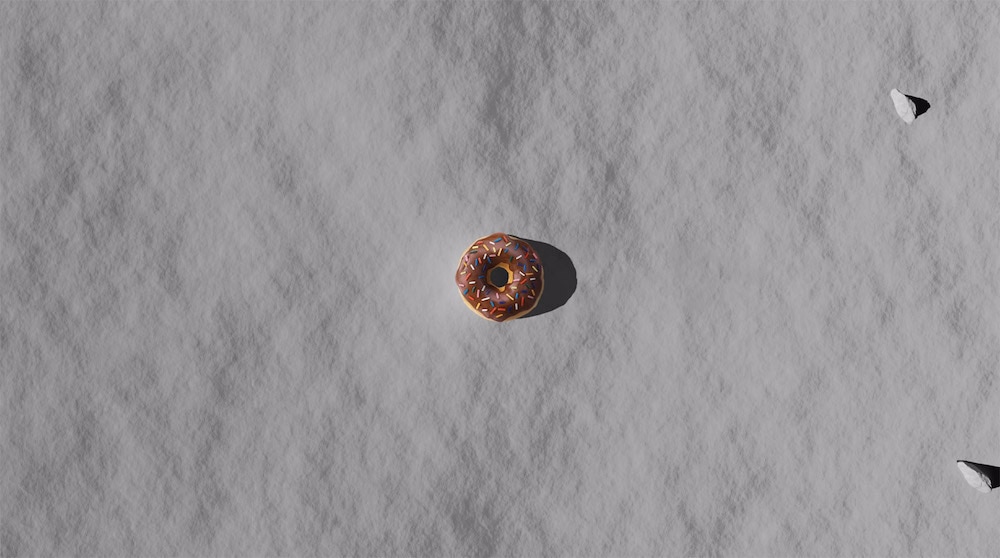

A donut on the Moon leads to a brain-bending optical illusion.

I was spending a slow Sunday morning drinking my coffee and procrastinating on Twitter — shocking, I know — when I came across a lovely video created by the European Southern Observatory. It demonstrates just how amazing the observations of the Milky Way’s central supermassive black hole are: The size of the ring of material around it on the sky is about the same as a donut would be sitting on the surface of the Moon.

The video itself is great, giving you a sense of just how small that would be by zooming in and in and in on the Moon, until you can see the donut sitting on the surface. I want you watch it all the way through — it’s less than 30 seconds long — and to pay particular attention to the surface of the Moon when the video stops zooming in. Why? You’ll see. Literally.

Did you see it? When the video stops zooming and the scene is stationary, the ground around the donut appears to move, looking like it’s receding from you, or sinking into the Moon! If you didn’t see it, watch the video again and don’t focus on the donut so much and relax your vision so you’re just taking in the whole scene at once.

The effect only lasts a few seconds, but when I first watched it was overwhelming; I couldn’t stop it from happening even if I tried. I literally laughed out loud — I love optical illusions — and had a pretty good idea of why it happened. I did a little poking around and sure enough, I was right.

First, this effect is colloquially known as the waterfall illusion, after it was described in the early 1800s by scientist Robert Addams, who noticed that after staring at a waterfall’s downward motion for some time, when he looked at the rocks around it they appeared to be moving upward. He was by no means the first person to observe this — Aristotle wrote about it — but he did popularize it.

The more scientific term for it is motion aftereffect, and like many illusions the cause of it is actually quite complicated. To simplify it, though, your eyes see a scene and send signals to the brain about things like overall brightness, contrast, and the like. They do this rapidly, over and again, and the brain then tries to make sense of those signals.

If something moves over time, its position will change relative to other objects in the scene, and your brain has neurons that can detect that motion. Some are sensitive to motion to the left, others to the right, some up, some down, and so on. Your brain is constantly comparing these signals it gets, contrasting them to get a sense of motion.

If you watch something that continuously moves in one direction, say downward, then the neurons that sense that motion are being activated, while the ones that detect upward motion are not. After a while the downward-sensing neurons get tired, fatigued, and don’t get activated as strongly. The upward sensing neurons are still sending the same signal they always have been, though, so when the downward signal weakens it thinks the upward signal is getting stronger. So when you look at the rocks at the side of the waterfall they appear to move up, even though they’re actually stationary.

Same thing with inward and outward motion! When the lunar zoom-in stops, the neurons that detect it are tired, but ones that detect zoom-out are not, so the surface of the Moon around the donut appears to move away from you. To me it looks like it’s subsiding, sinking into the Moon. Cool, and more than a little weird.

This is more than just a trick of the eye and brain, though. Studying these effects help us understand how our organs work, and that can lead to some interesting and important science.

For example, when I was a kid there was this popular trick where you stand in a narrow doorway and raise your arms to your sides as if trying to widen the doorframe. You’d do this for a few seconds, then relax your arms. When you do, there’s a strong sense that your arms are starting to float up again! This is called the Kohnstamm phenomenon, and is similar to the waterfall illusion except it deals with involuntary muscles. Scientists have looked into seeing what happens if the person does this trick and then tries to suppress it by holding their arms down at their sides. They found that the brain suppresses the involuntary lift signal before it reaches your arms — this could have implications for people who suffer from involuntary movements, like with Parkinson’s disease or Tourette’s syndrome.

I love illusions because they’re fun and trippy, but also because they give us a lot of insight into how we perceive the world, and how our brains and sensory organs work. That, in turn, can help scientists mitigate diseases that affect our perceptions.

And another underrated aspect is that they tell us that how we do perceive the world is not how the world really is. Despite what so many people think, seeing is not believing.

I've written about illusions dozens of time; like this one on how we perceive colors, or the perception of contrast, or color and contrast, or of illusory motion, and this absolutely maddening one on how we see shapes. Enjoy!