Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Mars InSight finds no ice to a depth of 300 meters below the surface

Where did all the Martian water go? Not Elysium Planitia, apparently.

We talk a lot about Mars being dry, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t have water: It means there’s no liquid water to be found. Instead, it’s in the form of ice.

There are millions of cubic kilometers of water ice frozen at the Martian poles. Small asteroid impacts have revealed water ice just below the surface at mid-latitudes, too; the impact excavates material from below, exposing the ice.

The equatorial regions have been more of a mystery. It’s cold enough in most spots there, especially below the surface, to support long-term water ice. But is it there?

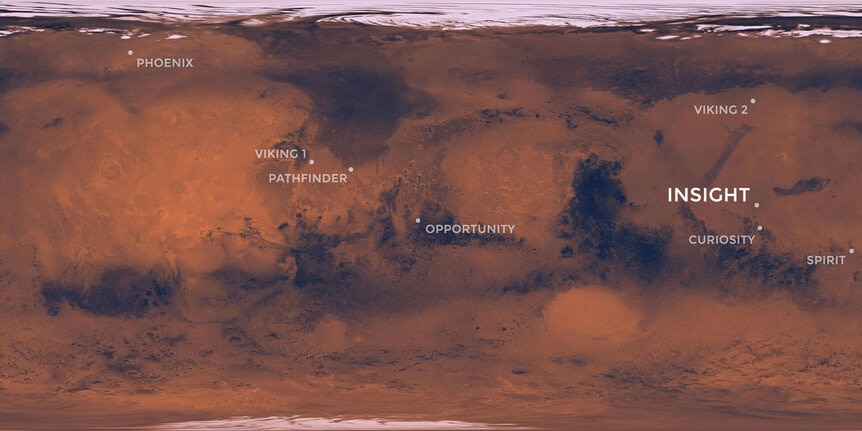

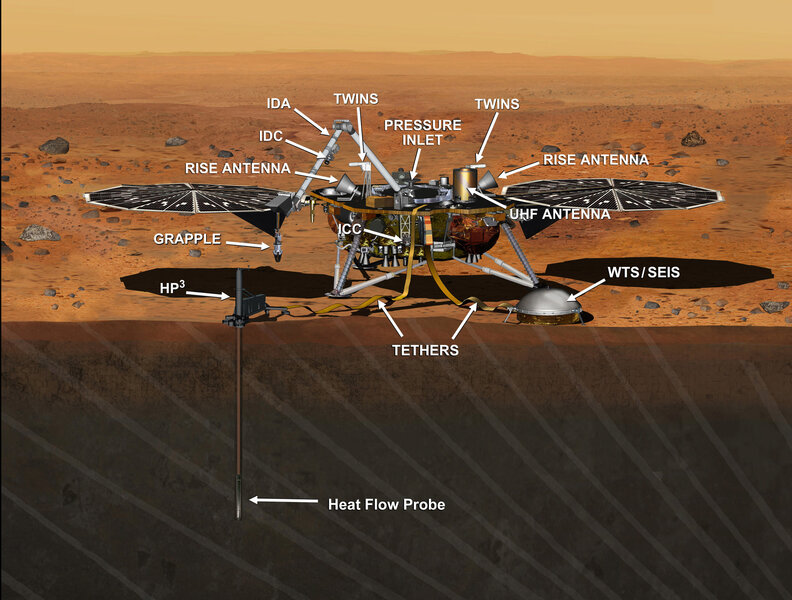

The answer is no, at least not in one spot in western Elysium Planitia. That’s a large flat region on the equator where NASA’s Mars InSight lander touched down. InSight’s mission is to probe the interior of Mars using various devices, including a seismometer called SEIS — the Seismic Experiment for Interior Structure — a heat probe to sense how heat flows through the surface from below, and more.

SEIS has detected well over a thousand marsquakes since it landed in 2018, including several large ones. These can be used to probe the interior of the planet — in fact, much of what we know about the interior of Earth is due to measuring the seismic waves from earthquakes as they pass through various layers below. Some waves move through solid material but don’t pass through liquid, the waves can get bent or reflected off of layer boundaries, and the speed of the waves changes through different materials. Geologists use all of these to map the interior of Earth.

The same is true for Mars. Using SEIS data, a team of scientists has mapped the change in the velocities of waves passing through the surface under InSight. They used models of the physics of rocks to determine the most likely composition of the material there.

Their conclusions are surprising [link to paper]. For one, they find little to no evidence of any water, ice or liquid, to a depth of 300 meters below InSight.

We know Mars had copious liquid water on its surface billions of years ago. It’s not completely clear what happened to it, though a leading idea is that the core of Mars lost its ability to generate a magnetic field, and when that collapsed the solar wind stripped Mars of most of its air and water. But it’s possible that much of the water seeped down into the surface and still exists as frozen aquifers, though how widespread they’d be is anyone’s guess.

These new results preclude the existence of any frozen lakes under InSight.

And there’s more. Or less, I suppose. The best fit using the models to the structure under InSight also indicate that it is made of sediments and fractured basalt, but this material is not cemented. Cementation is when material has flowed in between grains and solidified, hardening them into place. But the InSight results imply the material there has no cementation, so it’s not solid. It’s fractured.

The rocks in this area of Elysium are basaltic, lava outflows from nearby volcanoes. Over time this kind of rock can fracture and form small rocks or grains; there’s also evidence for sediment under the surface.

This material isn’t solidly packed, so it’s possible in theory that water can seep into the space between grains. However, the models indicate that at most water can only comprise about 20% of those seams. That’s a small fraction of the material there. Rocks exposed to water can also absorb it, creating new minerals, but again there’s no sign of that in the InSight data.

This result stands in opposition to the idea that large quantities of water could have seeped into the ground. At least, not at that location. It’s still possible that it could have happened elsewhere, and that Elysium in this area was dry. As an example, the Galileo mission to Jupiter dropped an atmospheric probe into the planet and found much less water than anticipated. But it turns out it fell into an unusually dry spot in the Jovian atmosphere; there was water found in adjoining regions of Jupiter. Imagine aliens sending a probe to Earth and landing in the Sahara; extrapolating from that to the whole planet is fraught with issues.

So maybe that’s what’s being seen by InSight in Elysium Planitia. There is evidence for water flow about 1,600 km away from InSight in Cereberus Fossae, which may have carved a valley into the surface. That’s a ways away, but shows that it’s possible that Mars may have dry spots as well as regions where water ice exists under the surface.

The lack of water is disappointing, if you’re hoping to find evidence of life. First, the presence of water at all would be beneficial; it’s an excellent medium in which chemicals can mix up and create complex molecular precursors for life. As far as we can tell, without it life is not possible. Also, cementation by water or minerals created by water would help preserve any signs of life from long ago. Without that, those signs may be gone.

Mars is a difficult place to understand. It may have started off similar enough to Earth, but our paths strongly diverged three or four billion years ago. Water still plays a huge role on Earth, but much less of one on Mars now. But it does still exist there, if only frozen, and our best chance of understanding what happened to Mars eons ago, and whether life ever got a pseudopodhold there, is understanding where that water is.