Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Dozens of rogue planets found in a nearby cosmic nursery

Starless planets wander the galaxy in the dark.

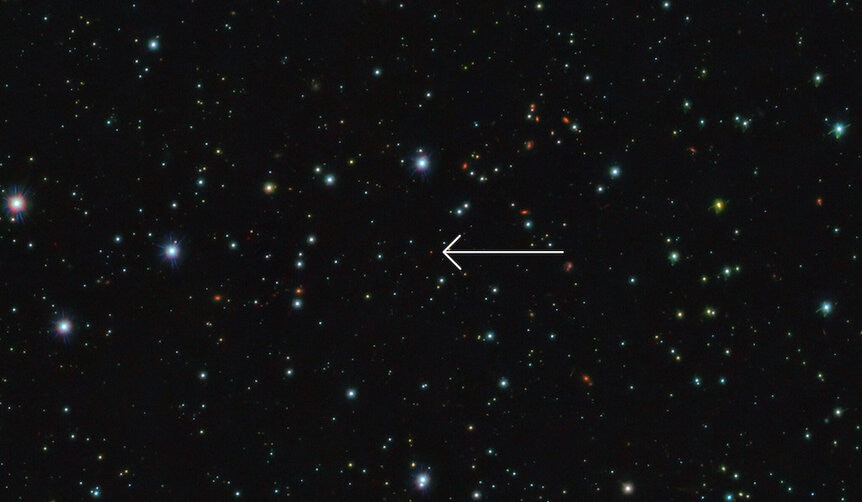

Complementing archived observations over two decades with new observations of the sky, astronomers have found a clutch of free-floating rogue planets — planets not orbiting stars, just out there in space on their own — in a nearby star-forming region. And it's not just a few: They tagged from 70–170 of them!

Free-floating planets are pretty much as their name advertises: Starless planets, doomed to wander interstellar space. We actually don't know much about them. The first were discovered in the 1990s, and while quite a few have been found since (and one under some pretty unusual circumstances), they tend to be discovered one by one, so it's difficult to get a census of them.

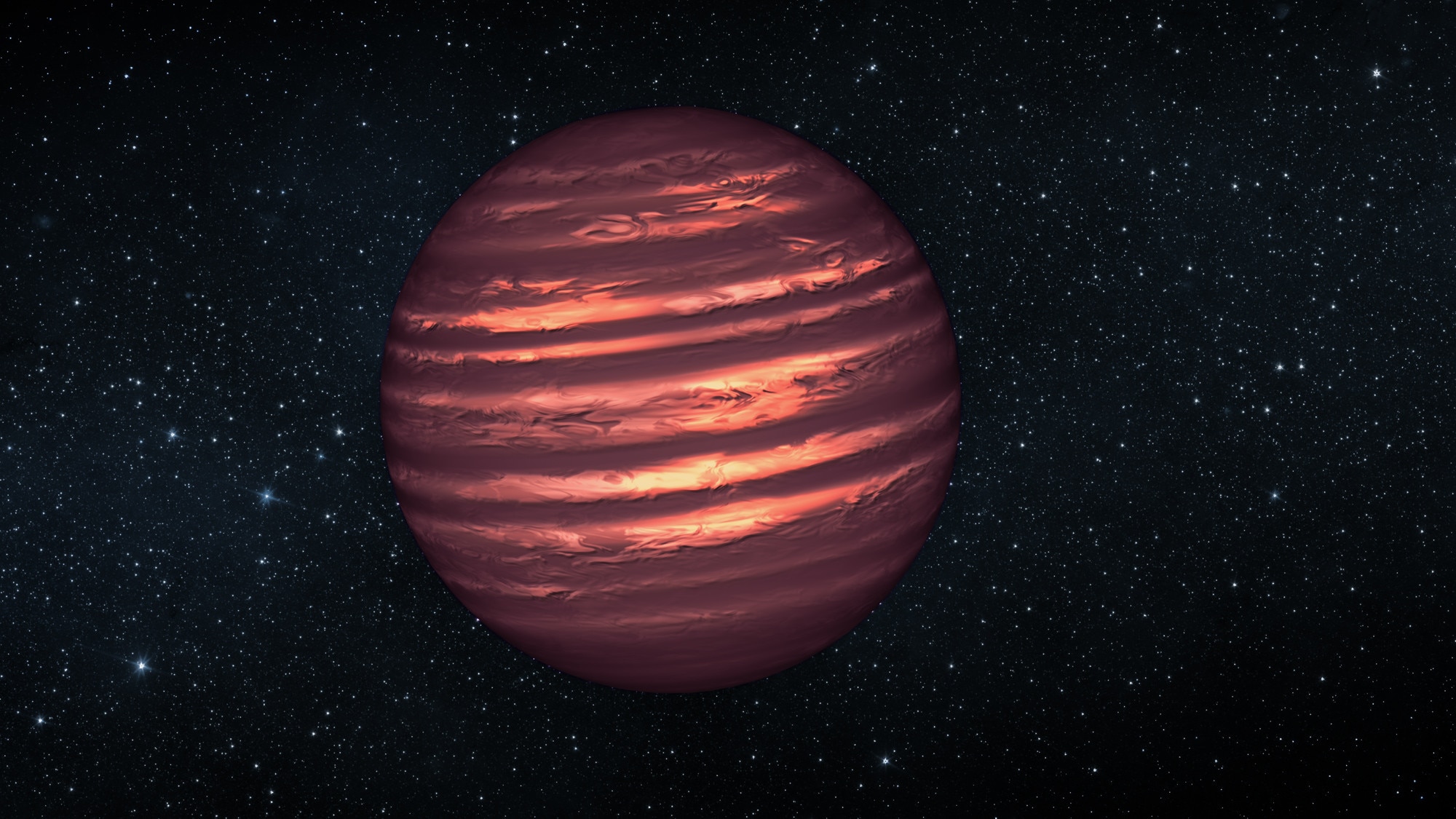

The ones found tend to be very young, so recently born that they're still very hot from the process of formation. That means they glow in infrared, making them observable in telescopes and cameras tuned to that wavelength of light that the human eye can't see. They cool as they age, eventually getting harder and harder to detect, which is why most of the ones known are young.

They can be identified in a variety of ways. A key point is knowing a planet's age: Because they cool as they grow older, they shine at different wavelengths (colors) of infrared light depending on their mass — a more massive planet will take longer to cool, so will be hotter and therefore brighter at a given age. We have pretty good models of how bright an object should be given its age, so that can be used to estimate its mass.

To look for rogue worlds, a team of astronomers looked toward Scorpius and Ophiuchus, a pair of constellations where a huge star-forming cloud lies, one of the closest to Earth. Why there? We don't know how all free-floating planets form, but we're pretty sure they either come from gas and dust clouds that collapse on their own, similar to the way stars are born, or they form around stars and get ejected — and the latter is the far more likely cause for lower mass planets. Orbits of planets around young stars can change rapidly, and if a planet gets too close to another more massive one it can get ejected, tossed out of their planetary systems entirely.

Apropos of nothing, I'll note that this region is one of my favorite areas of the sky, noted for the staggeringly beautiful Rho Ophiuchus cloud complex, and if mentioned I will always take the opportunity to show off a photo of it taken by astrophotographer Rogelio Bernal Andreo:

Would I lie to you? Wow. And besides its beauty it holds much scientific value.

The observations in this new research are pretty serious: The astronomers looked at 171 square degrees of sky (about 850 times the area of the full Moon) using observations from 18 different cameras over 20 years, processing nearly 81,000 images in total, and finding over 26 million objects. This then became their catalog to search in, for a project they call the Dynamical Analysis of Nearby ClustErs (or DANCe).

They then turned to Gaia, a European Space Agency mission that has mapped the positions, motions, distances, and colors of well over a billion stars. They used that to get the distances to the objects in their catalog, looking for ones that could be in the Sco-Oph cloud. They found a bit fewer than 3,500 candidate objects (including stars), about 20% of which had not previously been identified as being part of the star-forming region.

Picking out the objects with planetary mass isn't easy. It depends on the object's age, and the objects forming in the Sco-Oph cloud have a range of ages, from 1 to about 10 million years. So what they did is take a handful of specific values for age and calculated masses based on each. What they then found is that at least 70 and as many as 170 of their objects have the mass of a planet, depending on the age assumed.

This is significant. A planet has a mass up to about 13 times that of Jupiter. Around that mass, an object can generate enough pressure in its core to fuse deuterium, an isotope of hydrogen. We call such objects brown dwarfs, and they run from 13 up to roughly 75 times Jupiter's mass — at the upper limit they can fuse hydrogen proper into helium, the definition of a true star.

At the high mass end brown dwarfs form like stars, collapsing directly from gas and dust. At the low end they can form like planets, aggregating material from a disk of debris around a newly forming star. It's also possible high-end planets might form that way as well, so the more we know about these free-floating planets the better we can understand how they — and star-bound planets — form.

Part of this is knowing how many are born from a given cloud. We know, for example, that low-mass red dwarfs are the most common kind of star, with stars like the Sun making up less than 10% of all stars. Truly massive stars make up a much smaller fraction. This dependence of number on mass is called the initial mass function (or IMF), and is the basis of a lot of our understanding of how stars and galaxies behave.

It's not well known down at the very low mass end because objects like that are faint (the first brown dwarf wasn't discovered until the 1990s). A lot are known now, but it helps to have a complete census of a single star-forming region, so we know what the IMF is from soup to nuts. Getting a better handle on the IMF is really the purpose of this search for free-floating planets.

They found that of the 3,500 objects found, about 4.5% are rogues, with a somewhat large uncertainty due to the age of the objects not being known well. Still, that's very helpful. And pretty amazing, that we can find such things at ll.

… and whenever I write about these rogue planets I smile to myself. When I was a kid and spending every waking minute watching science fiction shows on TV, sometimes the plot would revolve around a rogue planet (Star Trek and Space:1999 both featured them). I clearly remembering thinking that was silly. How could such a thing exist?

But nature is more clever, more imaginative than I was. It makes lots of rogue planets, and just the fact that they exist tells us something about the history of planetary systems, even ours. How many planets did the Sun once have, back when it was young, and how many of them were thrown out into the cosmos, orbiting the galaxy on their own in interstellar space for all those billions of years since?