Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

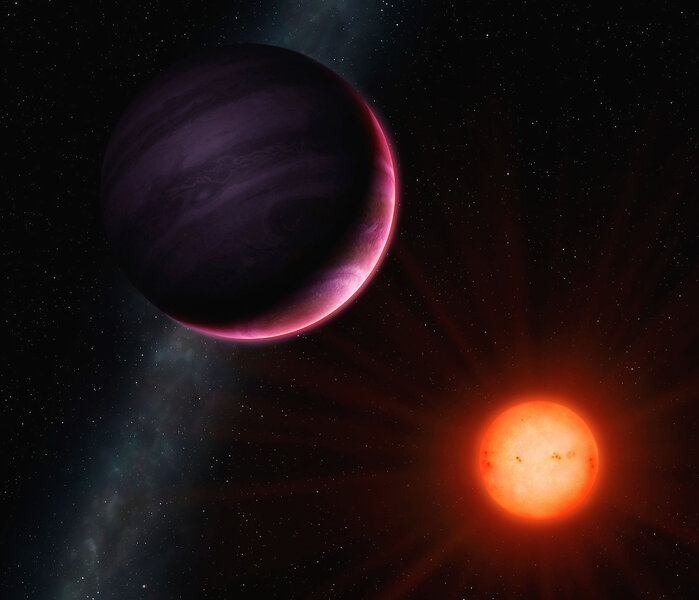

Rare beast: An eccentric Neptunish exoplanet orbits a nearby red dwarf star

Big planets around tiny stars are very uncommon.

One of my favorite aspects about the vast number of exoplanets detected so far — coming up on 5,000 of these alien worlds — is that with so many discovered, you can see trends in their characteristics, as well as find oddballs that fall far from the trends.

In our solar system, for example, the planets are well-spaced and have fairly circular orbits. But that's not always the case.

TOI-2257 is a red dwarf, a small, dim, low-mass star about 188 light years from Earth. It has about 1/3rd the mass and diameter of the Sun, looks to be about 8 billion years old — much older than the Sun — and is so faint at that distance that it blends in with the millions upon millions of stars around it.

Except in 2019 the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, or TESS, noticed the star dimming for a short time, then brightening again. This behavior repeated 175 days later as well. It only dimmed by about 0.4%, but that has the signature of a transit, when a planet orbiting the star blocks its light as seen from Earth in a mini-eclipse.

An alert was sent out to planetary astronomers, and a team jumped on it. If the planet has a 176-day orbit it would be six months before they could see another transit, but TESS didn't watch it continuously, so it's possible it might have had a shorter orbit with some simple fraction of that period, like a half or a third.

Follow-up observations ruled out the 57-day orbit — one-third of 176 — but more observed transits established the planet had a 35.2-day orbit, or one-fifth of 176 — so it's year is a little over one Earth month.

Once confirmed, the planet was given the designation TOI-2257b.

How much light from the star is blocked depends on the size of the star and the planet. To drop this small star's light by 0.4% requires a planet about 2.2 times the Earth's diameter. From what we know about how planets form, that's a bit too big to be a rocky planet like Earth, because planets that size are big enough to start drawing in lots of gas around them as they form, becoming more like mini-Neptunes: a rocky core surrounded by a thick atmosphere. Models indicate the most likely mass for TOI-2257b is 5.6 times Earth's, though that's very uncertain. Neptune, for comparison, is a little under 4 times Earth's diameter and 17 times its mass.

That's already interesting. Red dwarfs are low mass stars and given what we've seen of their systems they don't generally have giant planets orbiting them. They're really good at making Earth-sized planets — TRAPPIST-1, a nearby dim bulb of a star, has seven small planets orbiting it. Also, those planets tend to be very close to the star — TRAPPIST-1's planets could all fit inside the orbit of Mercury around the Sun. A 35-day orbit is unusual, and for a red dwarf planets makes TOI-2257b technically a long-period one.

Where this gets interesting is when they looked at the orbit itself (link to paper). Modeling the transit behavior can give hints about the shape of the orbit; for example, if you assume a circular orbit the transit should take a certain amount of time, but if the orbit is elliptical the planet moves at different speeds at different times, changing the length of the transit duration.

What they found is that the best fit to the orbit gives them a decently elongated ellipse with an eccentricity of very roughly 0.5. That's unusual as well! The most likely reason is a second giant planet orbiting even farther out. Over time, the gravity of that planet can yank and poke at TOI-2257b's orbit, making it more elongated.

This gravitational tugging can also change the timing between transits — this method to look for more unseen planets is called transit-timing variations. None was seen. As it happens, in systems where a big outer planet yanks on an inner one, in general only one inner planet is seen. That's likely due to that outer planet disturbing the other planets so much they get ejected from the system. No other planets are seen orbiting TOI-2257, so it may imply the existence of another big planet in the system.

I give a public lecture called “Strange New Worlds: Is Earth Special?” where I talk about exoplanets and how Earth and the solar system compare to them. This TOI-2257 system is so different than ours! It may only have two worlds, both big, around a dinky star. TOI-2257b's orbit is more elliptical than any major planet in our system, too. It really shows how wildly different such planetary systems can be.

… except for one thing. At its distance from its star, the temperature of TOI-2257b is likely to be around the right value to support liquid water. Now, the planet is a gas giant so it doesn't really have a surface, but it will have clouds, and could have lots of water vapor in them. And if it has a big moon, it could be a water world in miniature; many outer solar system moons are loaded with water ice. Given models of such a system, TOI-2257b is unlikely to have a moon — the odds are about 1 in 7, given that it's close enough to its star that gravitational perturbation could cause its moon to be ejected. But it's not impossible, and looking for one would be interesting.

We know that life on Earth needs water, and water makes an excellent medium for the genesis and support of living matter. There may be other ones out there, but we know water, and we know how to find it. TOI-2257b is close enough and its star bright enough that future observations, like from JWST, could show us if there's any oxygen or water in its atmosphere. That's not conclusive as far as life goes, but it would be interesting.

With nearly 5,000 exoplanets and counting discovered, we're bound to find oddballs. But when those oddballs share characteristics with Earth I find that heartening. It's an imperfect match at best, but shows us that the Universe is capable of a lot of diversity, and that in itself shows us we need to broaden our outlook on it.