Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Bigger is better for the world's longest long-necked sauropods

Big stretch!

In 1993, audiences were introduced to eccentric entrepreneur John Hammmond and his dream of a theme park filled with cloned dinosaurs in Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park (streaming now on Peacock). After an accident at the park, prior to its grand opening, lawyers for the endeavor insist on a safety inspection (it’s shocking they didn’t want that earlier), which results in an invitation for paleontologists Alan Grant (Sam Neill) and Ellie Sattler (Laura Dern), as well as mathematician Ian Malcom (Jeff Goldblum).

The scientists are understandably skeptical, at least until they set eyes on dinosaurs for the very first time. The moment that Grant and Sattler first glimpse the sauropods, even before the audience does, and we experience the emotions behind their eyes, we know that all of us are in for something truly special. Their reaction is understandable. The sight of a sauropod herd peacefully traipsing across the landscape would be enough to silence even the most vocal critics. But we know something Hammond didn’t. We know his sauropods could have been even more impressive.

RELATED: The kids of 'Jurassic Park' and 'Jurassic World' — Where are they now?

In 1987, paleontologists from a joint Canadian and Chinese expedition uncovered a handful of sauropod bones in what is now northwestern China. The bones dated to approximately 162 million years ago, during the Jurassic, and came from an animal larger than any other of its kind. The species was first named Mamenchisaurus sinocanadorum and described in a scientific paper published in 1993, the same year Jurassic Park hit theaters. While paleontologists made every effort to accurately describe the animal, they were necessarily working with incomplete information. We, however, have the benefit of hindsight and a few decades more of paleontological data.

Andrew Moore, a paleontologist at the Department of Anatomical Sciences at Stony Brook University, and colleagues, recently took another crack at M. sinocanadorum in the hope of more accurately describing its anatomy and evolution. In the process, they revealed M. sinocanadorum as the longest known long-neck to have ever walked the Earth. The findings were published in the Journal of Systematic Palaeontology.

“Part of what my research focuses on is understanding the lineage of sauropod dinosaurs to which Mamenchisaurus sinocanadorum belongs. We’re going back to sort of re-evaluate the nature of taxonomic and anatomic diversity,” Moore told SYFY WIRE.

That re-analysis comes not from any new discoveries about M. sinocanadorum itself, but from an overall increase in knowledge about sauropods, which offers clearer comparisons than were previously available. In particular, paleontologists now have access to staggeringly complete sauropod necks from closely related species like Xinjiangtitan shanshanesis.

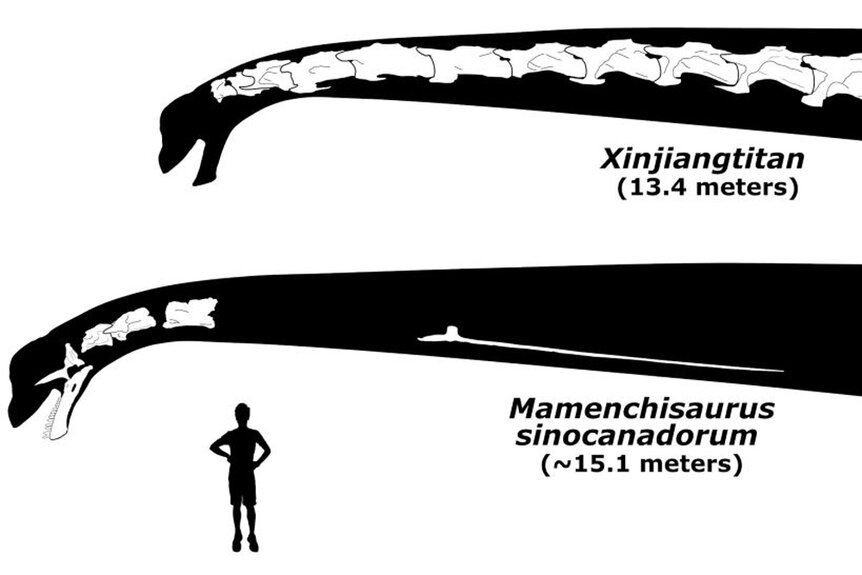

Xinjiangtitan is smaller than sinocanadorum, but barely. Its neck stretches an impressive 44 feet (13.4 meters) and we’re not missing any of the puzzle pieces. By comparison, M. sinocanadorum is known only from three cervical vertebrae, the lower jaw, and teeth, and a single rib. Importantly, the rib in question isn’t quite the sort of bone you’re probably thinking of. While sauropods did have the ordinary ribs, meant for protecting their vital organs, they also had 13-foot-long ribs running the length of the neck, providing additional support and protection.

RELATED: Sauropod dinosaur had the world’s longest and oldest sore throat

To figure out the total length of M. sinocanadorum’s neck, scientists compared the bones we have to the same bones in Xinjiangtitan. Once they crunched the numbers, they ended up with a neck 49.5 feet (15.1 meters) in length. That’s roughly six times the length of a giraffe’s neck, which is surprisingly difficult but equally hilarious to try and imagine. Let’s try a few more comparisons, just for fun.

M. sinocanadorum’s neck was about ten feet longer than a city bus. It was as long as three adult great white sharks laid tooth to tail. It’s one and a half times the distance needed to keep a football in play. It’s nearly twice as far as you’d walk in a duel before spinning around and firing your pistol. And it’s less than one ten-thousandth of a percent the length of the Great Wall of China. That last one doesn’t really work that well as a comparison, but it’s long. Especially for a neck.

“The most conservative estimate involves looking at Xinjiangtitan, comparing the bones sinocanadorum has, and scaling up from there. You get what’s called an isometric scaling relationship whereby these animals are presumed to have the same proportions, more or less. It turns out, that’s not the most accurate way to scale up sauropods,” Moore said.

That’s because sauropods are even weirder than you already knew. In mammals, relative neck length tends to diminish as an animal gets larger. For the most part, mammals need robust heads to accommodate strong chewing muscles. Just look at something like an elephant or a hippo, which has practically no neck to speak of. Sauropods took a very different evolutionary path.

“They are pretty unusual among vertebrates,” Moore said. “Their necks not only get absolutely longer as they get bigger, but they also get relatively longer.”

The upshot is that extrapolating from another species only gets you part of the way. Longer absolute size probably means they had even longer relative neck length. In short, M. sinocanadorum’s record-breaking neck was probably even longer than our intentionally conservative estimate.

RELATED: In order to survive some sauropods had the tooth fairy on speed dial

They were able to make such incredible necks at least in part, because they decided to ditch the concept of chewing, altogether. Instead, sauropods used their teeth to strip leaves and branches from treetops and swallow them whole. After a journey down their ridiculously long necks, all of that plant matter landed itself in the sauropodian belly, where it found a new definition of pain and suffering as it is slowly digested over a thousand years.

Nope. That’s the Sarlacc. Sorry. But it’s kind of the same thing. In the sauropod’s stomach, plant matter festered, broke down, and fermented until it became something the dinosaur’s body could digest and extract nutrients from. You can think of it almost like a giant walking compost-powered neck-building factory. Unlike other large animals, they were able to go all in on neck length by minimizing the head’s functionality and necessity in favor of reaching distance.

“It makes them efficient foragers, presumably. They are large animals that have to take in a ton of food every day. Having a larger feeding envelope makes your food gathering more efficient while planted in one spot. That's the going wisdom,” Moore said. And that makes intuitive sense, but it isn’t the whole picture. Sauropods have longer necks than other dinosaurs with similar trunk sizes, but mamenchisaurids like sicanodorum were building long necks even when compared with other sauropods. Why that is, isn’t wholly understood.

“Sauropods seem to be trying to build as long a thing as possible, in as fragile a way as possible, and that kind of tension is a really fascinating part of their biology,” Moore said.

InGen didn’t have any M. sinocanadorum at their island park, but you’ll be too busy running for your life to notice. Enjoy a vacation to Isla Nublar in Jurassic Park, streaming now on Peacock!