Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Bummer update: HD 131399Ab is not an exoplanet. It’s a star.

Well, nuts. It looks like we can scratch one recently discovered exoplanet off the list: HD 131399Ab is almost certainly a star, not a planet.

That's really too bad, because it would've made for a really cool planet.

HD 131399 is a star system about 300 light-years away from us. It's what's called a hierarchical triple, a pair of low-mass stars orbiting each other (called a binary), themselves orbiting a more massive star. It's part of a young cluster of stars, and using various techniques astronomers estimate their age at about 16 million years. That's young; the Sun is 4.5 billion years old.

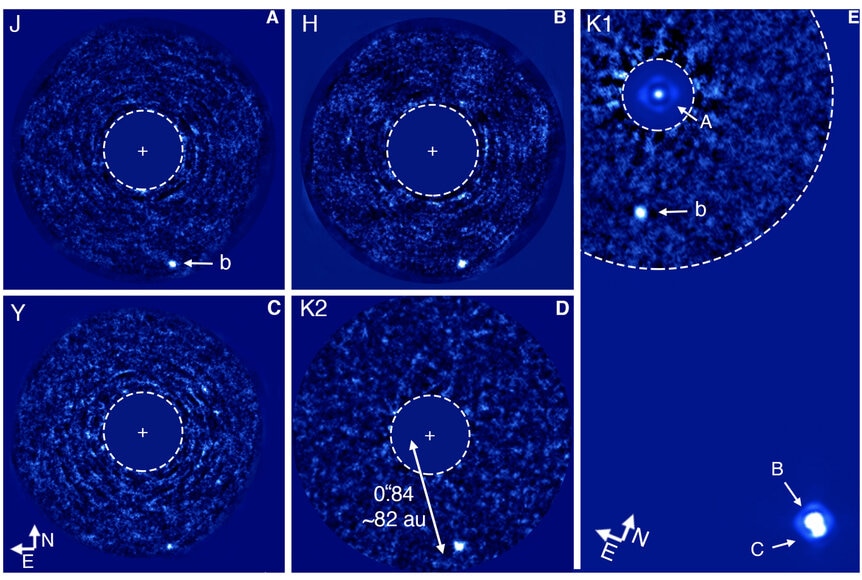

These kind of triple stars are relatively common, but what makes this one interesting is the presence of another object spotted in high-resolution images taken using the Very Large Telescope in Chile in 2015. This object appears close to the primary star in the system (called HD 131399A) and has the right colors and brightness to be a young planet, still glowing from the heat of its formation.

Just being in the picture doesn't mean it's physically associated with the system, though. This area of the sky has been observed for many years, though, so the astronomers who took the VLT images went back into the archives to find older observations. They did this to check the object's proper motion: Its physical motion in the sky over time. All stars orbit the center of the galaxy, so over time their relative positions in the sky change slowly. If the object is a background star you'd expect it to have a very different proper motion, but if it's a planet it should move along with HD 131399.

What they found was very interesting indeed: Over time, the object does appear to move along with the stars in the HD 131399 system! It wasn't a perfect match, but that was likely due (so they reasoned) to the object's orbital motion around the star itself. So they wrote up their results and published a paper in a scientific journal.

But, well. Not so much.

A planet like that generates a lot of interest, because the question of how it would form in a triple star system isn't clear, and knowing its orbit would be very helpful. Another team of astronomers decided to aim what telescopes they could at the system, and took observations with the VLT again as well as with the monster Gemini and Keck observatories. They very carefully measured the color and movement of the object to find out as much as they could about it.

And what they found was that it's far more likely to be a background star than an orbiting planet.

Like I said: Nuts.

The colors of a glowing object depend on its temperature (hotter objects are bluer, cooler ones redder), and for stars or young planetary objects the temperature depends on the mass. More massive objects are hotter and bluer. The colors of the object indicate it can't be any cooler than what's called a L0 type object, making it at least the mass of a brown dwarf, more massive than a planet. In fact the colors are most consistent with a K or M class star, cooler and redder than the Sun, but real stars nonetheless.

That doesn't necessarily exclude it from being a massive planet; when they're young they glow very hot and can shine like stars. But the problem there is that the object isn't bright enough to be a planet orbiting HD 131399A and still have the colors of a low-mass star. It's too dim, which implies it really is an M or K star, but much farther away from us than HD 131399.

Its proper motion seals the deal. Using very careful measurements of its motion in the images over time, the new research shows it's moving too rapidly to be in orbit around HD 131399A; at the speed implied it would leave the system rapidly. So unless we just happen to be catching it right after some event flung it away — and there's no obvious way this could happen given what we see in this system — it seems far likelier it's just a background star. It's farther away than HD 131399, but happens to have a similar proper motion, mimicking a planet bound to the star.

Reading over their work, this new research looks solid. I have to admit I'm disappointed, but hey, science. It progresses sometimes by showing that something we thought we knew is wrong, whether it's a principle of some kind or just a single fact.

I wrote about this "exoplanet" when it was first announced, and that research looked pretty good too, but looking back at it now with more experienced eyes I can see that the evidence to support the object being a planet was circumstantial. Really good, and convincing to me at the time, but not direct.

Funny, too: This new research was published back in July 2017, but I missed it. It's nearly impossible to keep up with everything being published these days! I happened to be poking around looking for something else when I stumbled on the new paper. Ironically, this happened right after I got home from giving a public talk on exoplanets where I actually show the image above of this system! That was frustrating. I don't mind having to update the talk and find a different cool exoplanet to show, but it irks me a bit that I can't go back and tell all those folks at my talk I was wrong! So if you were there, here you go. Sorry.

Ah well. We still have thousands of other confirmed exoplanets cataloged (including many we've directly imaged, like HR 8799's family of planets you can actually see orbiting their star over time!), and we're still figuring out how to do all this. It's inevitable mistakes will be made. What sets science apart is the ability, the necessity, to admit them when they happen and learn from them. It's built into the system of science itself, and it's how we humans better understand the Universe we live in. Science isn't perfect — scientists are only human, after all — but it's the best way we have of achieving that understanding.