Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

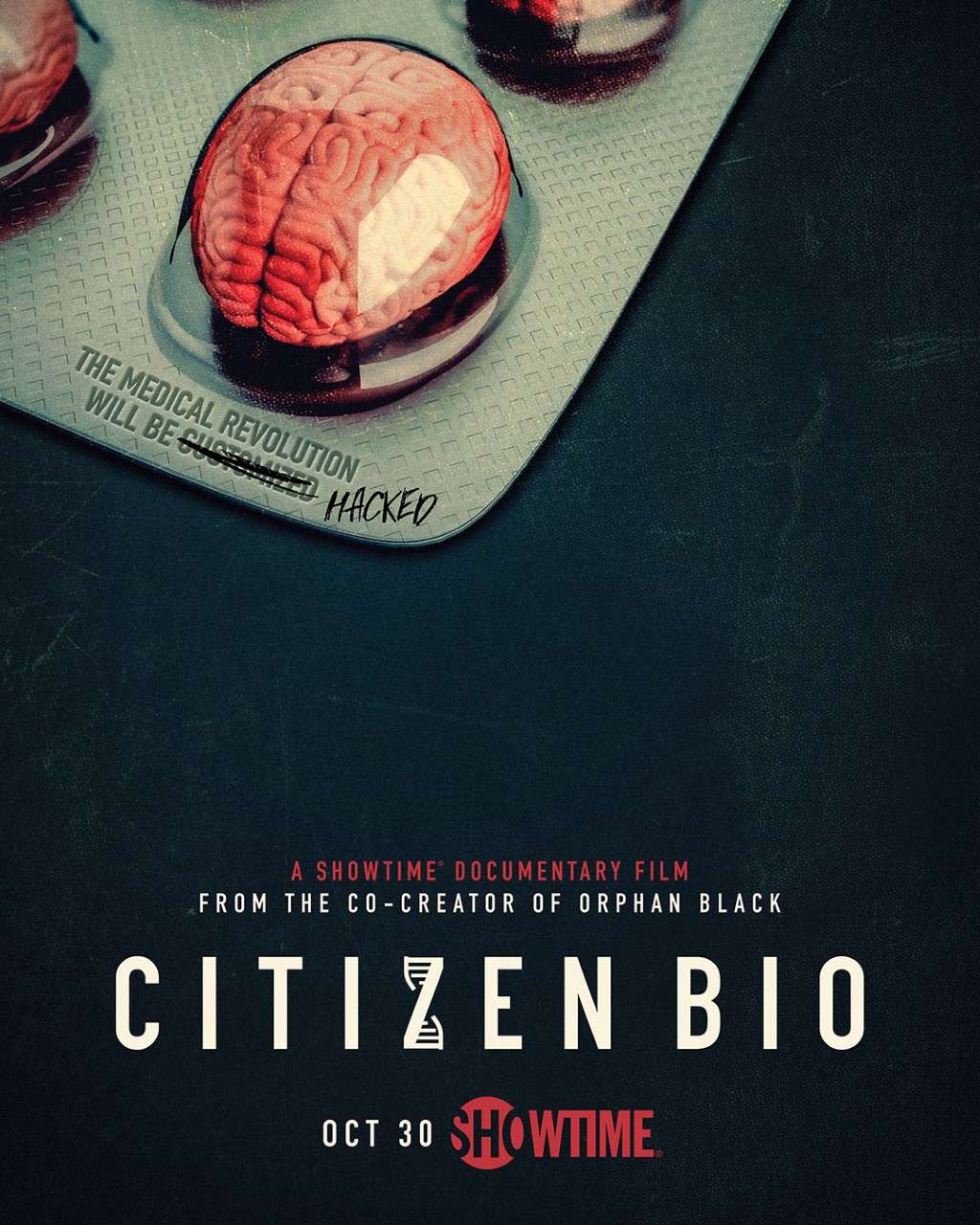

Showtime's 'Citizen Bio' takes a deep dive into the Wild West of biohackers' medical vigilantism

On the first shoot of the Showtime documentary Citizen Bio, director Trish Dolman and her longtime soundman, Brent Calkin, found themselves at a taser-knife fight in a California desert town.

The event capped a day filming body implant demonstrations and workshops at Grindfest, a grassroots gathering of “grinders,” people interested in augmenting their bodies with technology. One woman got a chip surgically inserted in her outer ear. A man whose face and head sported multiple piercings, a computer circuit tattoo, and implanted devil’s horns, had a subcutaneous RFID transponder that activated his motorcycle and home safes. To unwind, several grinders hacked tasers onto dull knives to competitively shock one another, leaving occasional souvenir burn marks on their skin. Calkin turned to Dolman: “Why do I always feel like every time I make a film with you, I'm going to get arrested?”

Welcome to the seemingly science-fiction world of biohackers, citizen scientists who experiment on themselves or conduct research outside of biomedical industry conventions to optimize and upgrade their minds and bodies, expedite cures, or synthesize faster and cheaper medicines. Grinders are a subset of this global community that applies science backgrounds and interests towards combating issues like disease, aging, and pollution — and even incorporating it into performance art. Part freak show, part medical vigilantism, biohackers have been known to inject stem cells and gene-splicing proteins, ingest microbiomes, or implant computer chips that transmit body data or activate devices. They’ve also indulged curiosities like bioengineering glowing beer with fluorescent proteins.

But often at its core is a humanitarian mission, with an eye toward making their findings open-source. “What I saw were people who really cared about society and the future of the planet,” Dolman, who also serves as the film’s co-executive producer, tells SYFY WIRE. “Their goals are quite altruistic and I didn't come across anyone with nefarious plans. I'm not saying they potentially don't exist, but it's certainly not what I observed in the community. It’s a group of people wanting to use science and genetic technology for the greater good.”

As entrée into the community, Citizen Bio focuses on the controversial biohacking company Ascendance Biomedical, whose charismatic leader, Aaron Traywick, was found dead two years ago in a Washington, D.C. meditation spa at 28. The company funded biohackers trying to prevent or cure such maladies as night blindness, HIV, and herpes. But Traywick ruffled feathers with outlandish claims of antidotes, displays like dropping his pants onstage to inject the herpes “vaccine,” and trying to wrest control of the research. Traywick didn’t die from biohacking — he was thought to have drowned in a sensory deprivation tank after police found ketamine in his pocket. However, his marketing tactics, promising cures, descent into mental illness and drugs, and misappropriation of company funds cast a pall on the movement that many bioethicists and scientists already deemed risky and delusional.

“In any movement, there are individuals who are not taking proper precautions,” Anna Wexler, assistant professor of Medical Ethics and Health Policy at the University of Pennsylvania, tells SYFY WIRE. “But from my work studying these communities, I’ve found most of them to be intelligent and concerned about safety.”

The 90-minute film profiles several of the Ascendance-supported biohackers, most of whom have some sort of scientific training. Josiah Zaynor, a former NASA researcher with a Ph.D. in biophysics from the University of Chicago, became the first person to genetically modify himself with CRISPR gene-editing technology. Gabriel Licina, who has an undergraduate biology degree, developed night-vision eye drops and is now engineering a plastic-eating fungus. Machiavelli Davis, who holds a bachelor’s in science, worked on gene therapy to mitigate HIV, which Tristan Roberts, a former computer programmer, injected in himself live online. Andreas Stuermer, who has a master’s in science, investigated a herpes prophylactic. Kennel operator David Ishee sought cures for canine genetic diseases. The Ascendance funding was a godsend for citizen scientists accustomed to relying on individual contributions or other revenue streams, such as Zaynor, who runs biohacking classes and an online supply store, The Odin.

“One of the reasons why we decided to look at the Aaron Traywick story was because it revealed the fragility and the weakness in the biohacking community,” Dolman says. “They need money to do what they do, which creates an opportunity for exploitation.”

The idea for the documentary came from Graeme Manson, the film’s executive producer (with Mackenzie Donaldson) and showrunner for TNT’s Snowpiercer. He came across the biohacking community while doing research for his hit 2013-17 BBC America series, Orphan Black, about cloned siblings. It was during this time that CRISPR was successfully demonstrated on human DNA, and subsequently disseminated through the biohacking community. Manson first contemplated a biohacking series, “but we found such a rich subject that we said, 'Let's make a documentary while we're doing our research.' Four years later, we've got our documentary,” he tells SYFY WIRE. “We were lucky to bring Trish onto the project for the right kind of punk rock filmmaking attitude for this subject.”

Based in Vancouver, Manson and Dolman have known each other for years. Manson cites Dolman’s 2011 documentary Eco-Pirate: The Story of Paul Watson as an example of her intrepid approach, which found her living at sea for months to chronicle the marine activist taking on illegal whale poachers and fishermen. Adds Dolman, “I am just fascinated by what some people perceive to be the fringe or subcultures, because they're the people who really push the boundaries of society and create social change.”

Citizen Bio filmed in more than half a dozen American cities, Vancouver, and China. “We discovered almost every city in North America has a community lab,” Dolman says. “It’s kind of combined with the maker movement — if there's a maker space in your city, there's probably a community lab in it. In California, they have incredible equipment because the universities give away all this scientific equipment when they get new stuff in. Information is spread by teaching each other. I met tons of people in these community bio labs who were completely self-taught working alongside someone who might have a Ph.D., or a startup doing their experimentation out of a community lab because it was way cheaper.”

Despite its renegade reputation, biohacking has an entrenched place in history, as scientists have often used themselves as test subjects — occasionally at their own peril. But sometimes it’s led to significant breakthroughs. Virologist Jonas Salk first tested his polio vaccine on himself and his children in 1952 before widespread trials. Chinese chemist Tu Youyou and Australian internist Barry Marshall earned Nobel Prizes for discoveries involving self-experimentation: Youyou for an antimalarial therapy she first tested on herself, and Marshall for proving Helicobacter pylori-caused stomach ulcers by drinking a batch of broth with the bacteria. And before grinders were a thing, British cybernetics professor and author Kevin Warwick dubbed himself the world’s first cyborg after implanting a silicon chip transponder in his forearm in 1998.

The Citizen Bio subjects, though, seem more intent on treatments for diseases that are incurable or too rare for corporate investment, or cheaper and less addictive alternatives to Big Pharma offerings.

“It’s generally a response to a gap in society, in particular American society, where you don't have equal access to healthcare,” Dolman says. “Biohackers are just taking it into their own hands.”

It’s also a reaction to socio-economic divisions that exist in science education, Manson adds. “Not everybody can take on a huge debt to go and get a science degree. But there are many smart people who shouldn't be denied this kind of education or the ability to practice," he says.

The pandemic has the movement undergoing a shift in perception as numerous biohackers tackle treatments for SARS-COV-2. “In the context of COVID, we’re seeing a number of biohacking endeavors try to fill gaps in treatment and diagnostics,” Wexler says. But now academics are supporting their efforts. “What’s different with COVID is that we’re seeing individuals with institutional connections get involved with DIY science endeavors — most famously with [Harvard University geneticist] George Church and his connection to the RaDVaC group.”

“A number of Citizen Bio subjects have joined those ranks as well. “You can go online right now and take a course from Josiah and David and learn how to make your own COVID-19 vaccines,” Dolman says. “Gabriel told me he had self-administered a COVID-19 vaccine that he developed with some other confidential doctors and researchers. Mac is selling one. Whether that’s legal or illegal, I have no idea...”

The practices, views, and opinions expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of SYFY WIRE, SYFY, or NBCUniversal.