Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Searching for extraterrestrial intelligence: The science behind 'Contact'

Contact is more based in science than most movies involving aliens. Here's the truth about SETI.

Over a quarter-century ago, famed astrophysicist and science communicator Carl Sagan and his wife Ann Druyan, Creative Director of NASA’s Voyager Interstellar Message Project, wrote a story about the search for intelligent life. That story, which began as a film treatment, became a novel, and then ultimately a film directed by Robert Zemeckis and starring Jodie Foster, came out 25 years ago this week.

In Contact, Foster’s character, Ellie Arroway, discovers an alien signal from another star and embarks upon a species-changing journey to meet them face to face. At least that’s her experience of events. The movie leaves its ending open to interpretation.

Having Sagan and Druyan, the minds behind Cosmos, at the helm of a science fiction story means that it leans a little closer to the truth than some of its silver screen peers and serves as an interesting opportunity to examine our ongoing search for life elsewhere in the universe.

SEARCH FOR EXTRATERRESTRIAL INTELLIGENCE (SETI)

In 1960, as interest in space was ramping up, a group of scientists got to thinking about all of the radio noise we were pumping out into space and wondered if we might be able to detect similar signals not from Earth, but from an extraterrestrial civilization. They figured, at the very least, it was worth looking into so they pointed a radio telescope located in Green Bank, West Virginia, toward the stars and started listening. They looked at two stars, Epsilon Eridani and Tau Ceti, both of which are about 11 light-years away. That search didn't turn up any alien signals, but it did launch the larger SETI project, one of humanity's most hopeful endeavors. It also inspired the events of Contact.

As the movie begins, Foster's Ellie Arroway is working for SETI at the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico. Arecibo is a real telescope — at least it was — and was the world’s largest single-aperture telescope for more than half a century until it was dethroned by the FAST telescope in 2016. In 2020, the telescope, which was built into a natural sinkhole, partially collapsed and it is no longer in use.

Prior to its tragic death, however, it was a part of the SETI program in addition to searching for near-Earth objects for NASA. That said, it wasn’t used in quite the same way as we see it depicted in the film. As is the case when adapting anything to film, even if what you’re adapting is reality, some concessions were made in favor of drama or visual appeal.

Shortly after the movie’s opening scenes, Arroway and colleagues lose funding and turn to a private donor to continue their work at the Very Large Array, a collection of 28 radio telescopes located in New Mexico. Like Arecibo, the VLA is also a real location that is indeed used, at least in part, in the search for extraterrestrial intelligence. Private funding is also true to life, much of SETI’s activities have been funded partly or entirely by private donations.

In the film, we see Arroway using the VLA to scan the heavens for alien signals which she, ostensibly, finds. In SETI’s own review of the movie, they noted that the VLA is actually not the ideal tool for this sort of work. They further stated that if you wanted to search for alien radio signals then Arroway and company had the right idea the first time around. Arecibo was four times larger and more sensitive than the telescopes at the VLA. That said, they also admitted that the image of radio telescopes stretching off into the distance offered a more visually interesting setting for the film. Sometimes, in Hollywood, that’s what counts.

The method of searching depicted on screen also mirrors activity carried out by SETI in real life, under the umbrella of Project Phoenix. Between 1995 and 2015, SETI utilized several telescopes around the world including the Parkes telescope in New South Wales, the National Radio Astronomy Observatory in Green Bank, and notably the Arecibo Observatory. It’s worth mentioning that the Very Large Array was not a part of the project.

Rather than scan the entirety of the sky for stray signals, Phoenix strategically pointed itself at approximately 800 Sun-like stars within a roughly 200 light-year distance. As far as we know, they never received construction diagrams for a complex interstellar spacecraft.

THE DRAKE EQUATION

Despite decades of dedicated searching, we have so far failed to find any confirmed evidence of extraterrestrial intelligence. Depending on your point of view, the lack of any clear signs of life is either entirely expected or shockingly unlikely. One way of quantifying which end of that spectrum you belong on is by considering the values you’d plug into the Drake Equation.

Appropriately, the Drake Equation was first proposed at the inaugural SETI meeting in Green Bank, West Virginia in 1961. That first meeting was a veritable who’s who of scientists interested in the search for extraterrestrial life. Frank Drake was there, of course. So was Melvin Calvin, a biochemist who received a phone call alerting him he had won the Nobel Prize during the meeting. Carl Sagan was also there, along with several others. Their aim was to determine whether or not the search for extraterrestrial intelligence was a worthwhile endeavor and Drake proposed his equation as a possible way to narrow in on an answer.

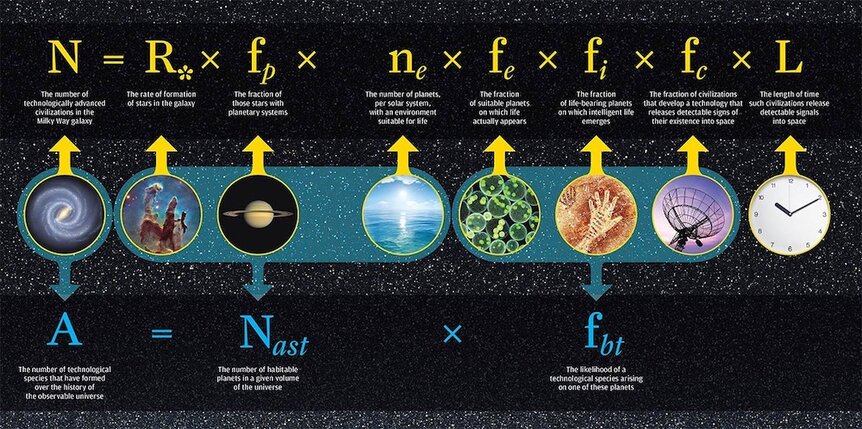

The equation looks at seven factors, all of which solve for N, the number of technologically intelligent civilizations in our galaxy. Those factors are as follows: The rate of formation of stars suitable for the development of intelligent life, the fraction of those stars with planets, the number of planets per system with a suitable environment, the fraction of those on which life appears, the fraction of those on which intelligence evolves, the fraction of those which develop technology we could detect, and finally the average length of time such a civilization persists and creates those signals.

We’ve got a pretty good idea of the number of suitable stars out there, at least as defined by the sort of life we might recognize. In recent years, with the increased discovery of exoplanets, we’ve developed a better idea of the second criteria and to a certain degree the third. The remaining four criteria are almost entirely a matter of speculation and, depending on the numbers you plug in, either suggest that the galaxy is brimming with intelligent life or that it’s tragically empty.

That we haven’t found even a whisper yet could suggest that the latter conclusion is likely to be true. Alternatively, it might be that we’ve only been looking for a short time on cosmic scales and the universe, even the galaxy, is a very large place.

In any event, if there’s even a chance that there’s someone else out there waiting to be found, the answer to the meeting’s initial question of whether it was a worthwhile endeavor is a resounding yes. No math required.