Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Did the Galileo spacecraft pass through a geyser plume over Europa? Maaaaaybe.

The astronomy scicomm community is buzzing over a paper just published by planetary scientists claiming they’ve found evidence that the Galileo spacecraft passed through a plume of water high above the surface of Jupiter’s moon Europa, ejected in a geyser.

Let me be clear: This evidence is pretty good, but it’s circumstantial. A lot of pieces do fit together here, but the puzzle is by no means complete.

Still. Hmmmm.

OK, so what’s what?

The Galileo spacecraft was an ambitious mission to the planet Jupiter that launched in 1989 and arrived at the massive planet in late 1995. It was an amazing mission, taking close-up images of asteroids during its journey, dropping an atmospheric probe into Jupiter, and taking incredible data and images. A problem with the main antenna (it didn’t unfurl properly, likely due to the mission being stored for years after the Challenger Space Shuttle disaster, and spending too much time in trucks getting shipped across the country during its testing) marred an otherwise fantastic mission, slowing the reception of data to a trickle. Still, we learned a huge amount about the gas giant from Galileo.

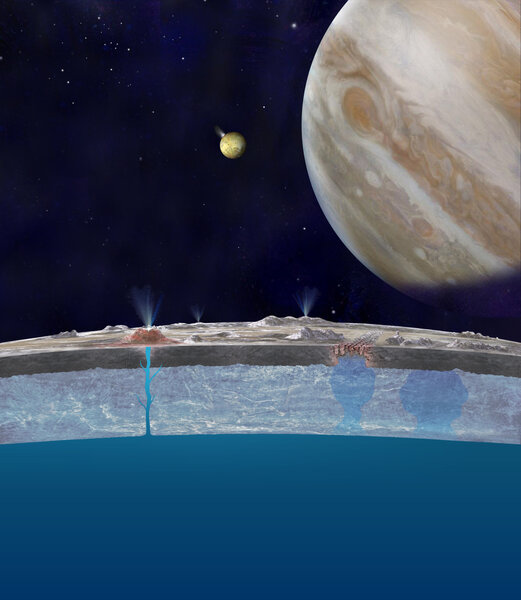

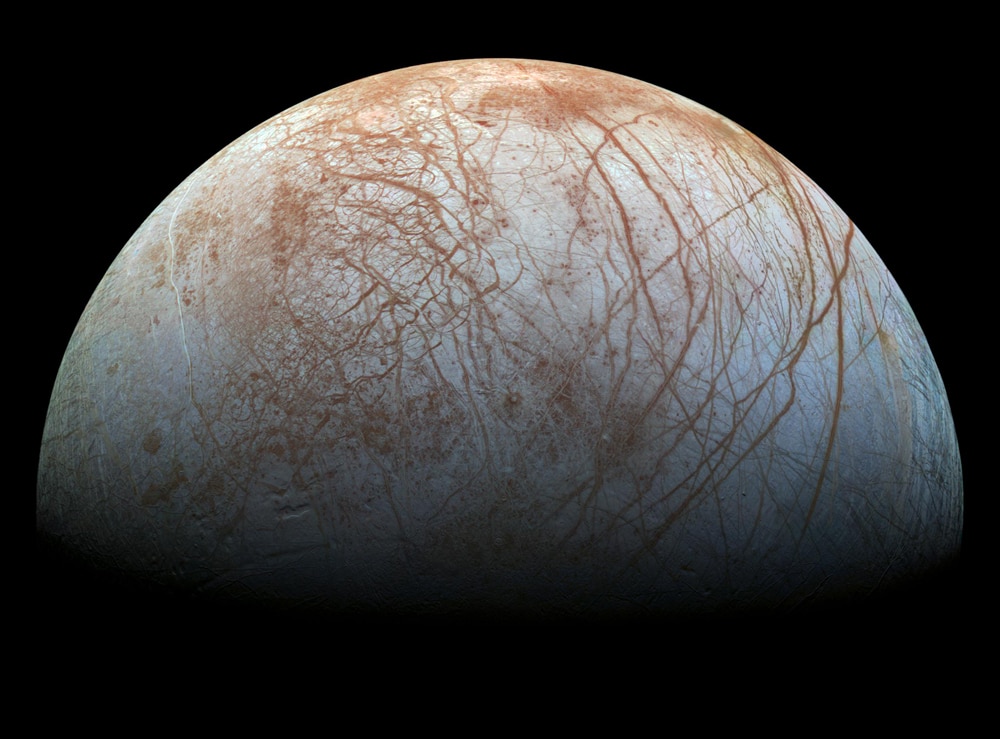

And its moons. Europa is one of Jupiter’s big four moons (called the Galilean moons, since they were discovered by (the human) Galileo), and at 3,120 km across is just smaller than our own Moon. It has a rocky core and has been known for some time now to have liquid water under its surface; it’s likely an ocean (as opposed to isolated pockets) as much as 100 kilometers thick and just a few kilometers below the frozen icy surface.

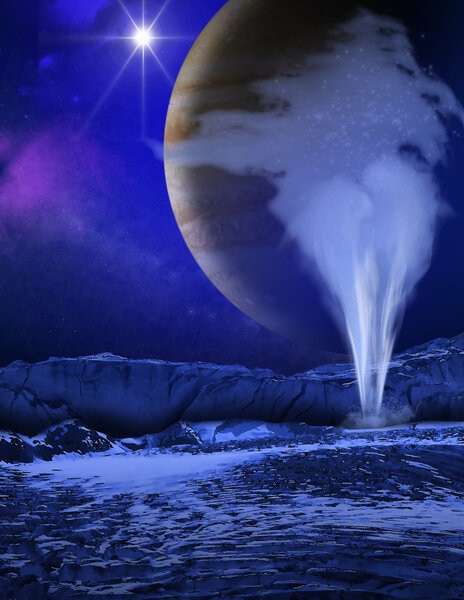

Here’s where things get interesting. In 2013, observations of Europa using Hubble Space Telescope indicated there might be an erupting geyser of water there. This was surprising but not shocking; we knew at the time that Saturn’s moon Enceladus has geysers galore erupting from its south pole, blown out from cracks there as Saturn’s mighty gravity squeezed and stretched the small icy moon.

So an ice moon erupting water wasn’t unprecedented. But, to be honest, the evidence from Hubble was good but not conclusive; other observations were needed.

Galileo made 8 flyby passes of Europa during its mission, and two of them were pretty close, under 400 km from the moon’s surface. In those two flybys, some odd data were recorded, indicating a change in the moon’s magnetic field. However, the data weren’t great, so not much was made of them.

Then a fun thing happened. During a talk by my colleague and old grad school buddy Melissa McGrath about Europa, Xianzhe Jia and his team realized that some warm spots on Europa discussed by Melissa sounded familiar. They dove back into the Galileo data and found that in one of the close passes, Galileo did indeed fly over one of those warm spots in December 1997.

At that time, computer analysis techniques weren’t as good as they are now, so using more sophisticated processes they re-analyzed the data. And they did indeed find an anomaly. Several, in fact. One is that the magnetic field measured by the magnetometer on Galileo showed a sharp change as the spacecraft passed over that spot. Not only that, but another instrument detected a rise in plasma density; that is, atoms or molecules around Europa that had one or more electrons removed.

Using 3D modeling of what a water plume from Europa would act like, they found a pretty decent fit to the data taken by Galileo. In other words, a plume of water blasted off the surface of the moon would explain much of the weird observations seen by the Galileo instruments.

Now mind you, consistency is one thing, but proof is quite another. What they found is pretty compelling, and even likely to be correct. But it’s not 100% clear. The models they used had a lot of free parameters (the location of the plume on the moon, the strength, its height and width, and even how tilted it was from vertical; many of the plumes of Enceladus are tilted quite a bit), so it’s hard to say how certain they are. Also, not every characteristic of a plume they modeled matched the data (for example, the data indicate small shock waves in the plasma which the model didn’t cover). However, the location they found is not too far from where the Hubble observations saw evidence of a plume, so that’s interesting.

But again, it’s hard to say. I’ll note that a second Europa flyby also had a magnetic anomaly seen, but Jia’s paper says it was unlikely to be due to a plume because the characteristics of the vent don’t match what you’d expect from a plume.

So yeah, this is exciting, and very cool. But if you want hard facts, well, the best bet is to go back and look*.

Happily, there are plans to do just that. NASA is looking into sending a dedicated spacecraft called the Europa Clipper sometime in the early to mid-2020s. Currently in the design stage, it will have a suite of instruments to examine the moon, including looking at the evidence for an ocean and seeing if it’s possible for it to be inhabitable. This isn’t all that far-fetched; a rocky core sitting under an ocean of salty water, plus energy injected by Jupiter’s gravity squeezing the moon, gives all the basic ingredients for life to arise. At the very least, the Clipper can be equipped with instruments that can sample the plume by flying through it, much as Cassini did when it flew through the plumes of Enceladus.

Not only that, but it’s possible a lander will be sent as a follow-up mission as well! You can’t get much closer than that. Though some scientists are dreaming of an idea where an actual submarine would be sent, or even just something that could drill down (or melt its way) into the ice to take a look at what’s down there.

What will we find?

No one knows. That’s why it’s exploration. But these observations we’re making, from Earth and in situ, are critical first steps in changing the unknown into the known.

*You may be wondering if Juno, the spacecraft currently orbiting Jupiter, can help. I don’t think so; the imager isn’t designed for that sort of thing, and it never gets close enough to Europa to get detailed data.