Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

The Haunting of Bly Manor's Mike Flanagan breaks down the series' ghost myths and 'hellacious' hauntings

When Netflix announced the acclaimed Haunting series would become an anthology with the arrival of its second season, it meant a lot of things. It meant the creative team had to shift focus to a different haunted house, moving from Shirley Jackson's Hill House to Henry James' Bly Manor. It meant that creator Mike Flanagan had to assemble a lineup of both new and familiar faces in front and behind the camera to tell The Haunting of Bly Manor's story as effectively as possible while still hopefully pleasing The Haunting of Hill House fans. And of course, it also meant that Flanagan and his new writers' room had to devise an all-new ghost mythology that would both satisfy new viewers and not repeat what came before.

"It's one of my favorite things about it," Flanagan told press, including SYFY WIRE, at an event the week before Bly Manor's launch. "The thing about hauntings are that they defy explanation because the more you try to explain them, the more ridiculous they can sound. And, they also create rules for themselves that become problematic.

"Like, if the ghost is there because they're murdered before their time and they wanted revenge and now they're killing other people, why don't they get to be ghosts?" he continues. "Why don't all the campers at Crystal Lake also get to come back and kill everybody? Who gets to make the haunted videotape [in The Ring], and who isn't allowed to make the haunted videotape? Those are the crazy rules that drive me a little nuts, as a fan. So, coming up with some kind of explanation for why Bly Manor is the way that it is, but another house that's just as old up the street presumably isn't crawling with ghosts, that's really fun."

The Haunting of Hill House certainly had its fair share of ghosts, but for Flanagan and his team, Bly Manor presented an opportunity to dig even deeper not just into the history of the ghosts at the house — something he'd hoped to do with Hill House before running into time constraints — but into the reason the ghosts are there in the first place.

**Spoiler Warning: There are spoilers for The Haunting of Bly Manor ahead.**

Though we have to wait until nearly the end of the series to see it, The Haunting of Bly Manor's title event actually begins centuries before the main story, with Lady Viola (Kate Siegel) and the "gravity well" of pure, almost superhuman will that surrounds her life and death, as she's determined to retain control of the manor house she loves so much. The eighth episode of the series, a black-and-white period piece that owes a great deal to both James' story "The Romance of Certain Old Clothes" and Jack Clayton's classic film The Innocents, provides an origin story for the featureless, smoothed-over faces we see on ghosts throughout the series, as well as the muddy footprints that show up in the halls of Bly in the mornings. It all ties back to Lady Viola, who continues to walk out of the lake each night and roam the grounds, desperate to reclaim what's hers and, frequently, dragging the living back down with her.

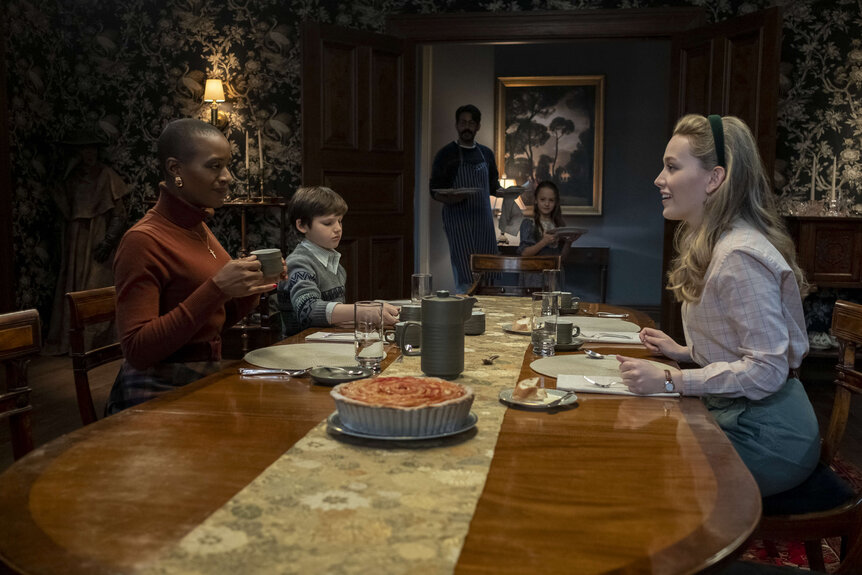

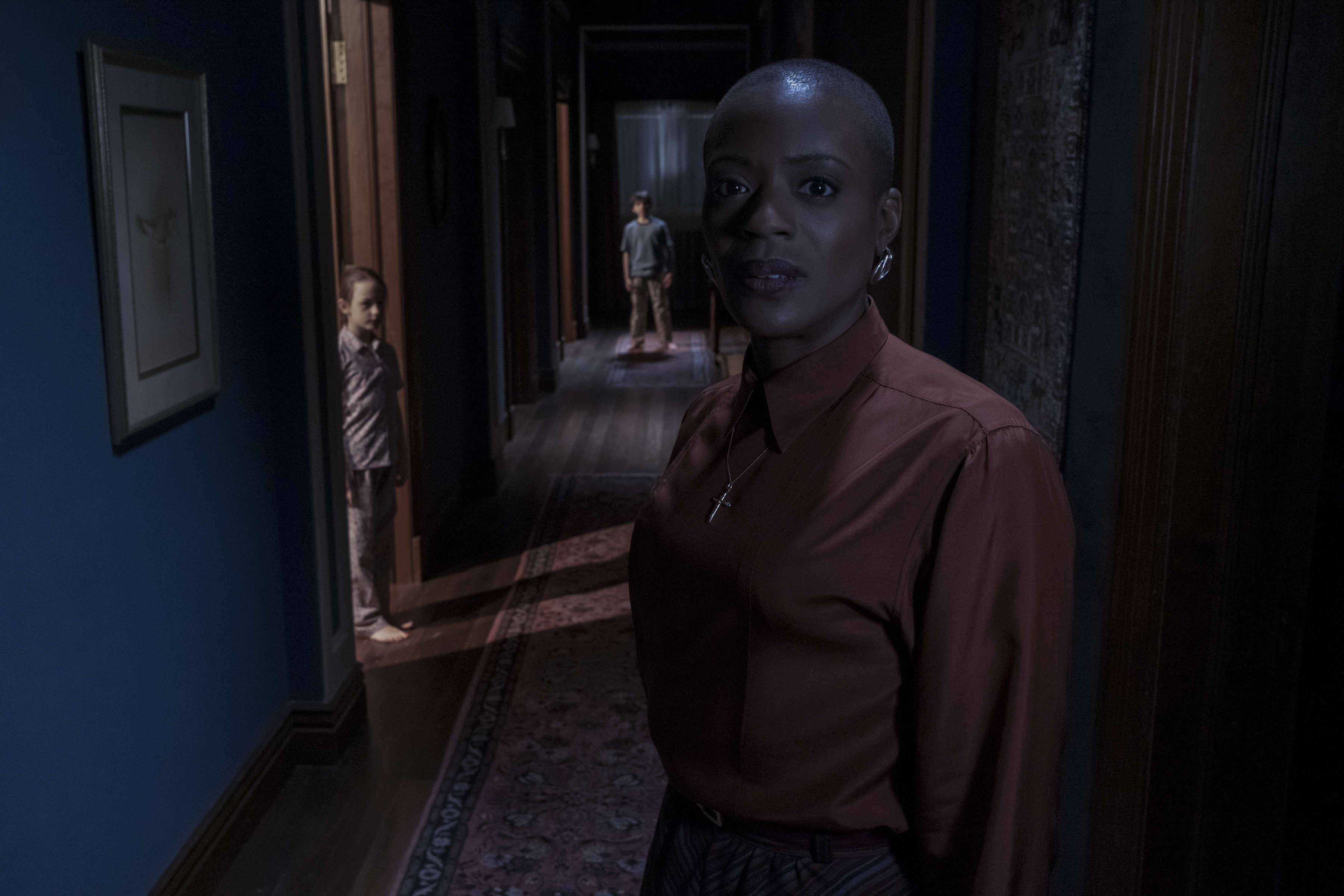

As creepy as the smooth, eyeless faces of the spirits of Bly are, though, Flanagan and his writers wanted to dig deeper into the more metaphysical effects of the haunting that begins with Viola. Discussions of how to do that ultimately led to the entire nature of Hannah Grose's (T'Nia Miller) experience as a ghost, which is revealed throughout the fifth episode of the series.

"If you die on the grounds of Bly Manor, the first thing that happens is you go through a period of intense denial. And that's where we have Hannah," Flanagan explains. "So, the idea was that this first stage of it was this kind of dreamed life that people could still carry on. They could dream up new clothes for themselves, which Hannah does. It's why she keeps kind of changing her outfit scene to scene. [They can] physically interact with the world, appear to people, because they're always putting out the effort, because of muscle memory and denial, basically.

"But, then once you accept the fact that you're dead... a whole bunch of the rules immediately change," Flanagan continues. "Once that realization kicks in, you're no longer able to reliably affect the world physically. And, at that point, your experience of your life, as you try to experience this new way of living, becomes very nonlinear. At that point, you're kind of involuntary bouncing back and forth between 'What is the present? What is the past? What is the future?'"

The concept of ghosts having a nonlinear existence is something Flanagan and his team carried over from The Haunting of Hill House, which featured the terrifying reveal that the ghost known as the Bent-Neck Lady was actually Nell Crain, who died in the house as an adult and then appeared as a ghost to her own childhood self. For Bly Manor, though, the concept expanded to include the idea of what Flanagan calls "dream hopping," the notion that ghosts not only perceive time in a nonlinear way, but also suffer a certain level of memory deterioration even within that nonlinear existence.

"What was really fun to play with here was that idea of the decay of memory," Flanagan says. "You know, they say we each die twice. We die when our body ceases to be, and then we die when we're forgotten, right? So, that idea that a ghost is subject to that deterioration, that as their own memories fade, and people's memories of them fade, the ghost kind of physically fades, all the stuff goes away but their memories become less and less reliable. So, that's what Hannah is going through the entire time."

While Hannah represents the upper crust of this development in the series' fifth episode, which sends her careening through various good and bad memories as she begins to realize she's dead, the characters of Peter Quint (Oliver Jackson-Cohen) and Rebecca Jessel (Tahirah Sharif) represent a somewhat deeper deterioration, as Jessel relives the highs and lows of her toxic romance with Peter, and Peter keeps revisiting a confrontation with his mother that forces him to relive his own internalized trauma over and over again.

"As a proper little atheist like I am, that to me is hell," Flanagan notes of Peter's situation. "It's not a lake of fire. It's that, when we're dead, we live in our moments of the most shame or regret, and if we're stuck there, the repetition of that, I think, is about as hellacious as anything I can imagine. So, Peter is off in that world."

All of this background building up the mythology of how ghosts at Bly Manor work — from the deterioration of memory to the dream hopping to the featureless, muscle-memory driven figures that make up the manor's oldest ghosts — is given an exclamation point in the reveal that the children of the manor, Miles (Benjamin Ainsworth) and Flora (Amelie Bea Smith), are behaving strangely specifically because Peter has found a way to use their bodies as vehicles for his and Rebecca's potential resurrection. It's why Miles curses and cracks mean jokes, why Flora seems to lose track of where she is, and by extension why Rebecca died in the first place — because Peter was determined to drive her body to death so their ghosts could be together in the ultimate act of violation and betrayal.

"More and more frequently, as Peter gets better at doing this and [Rebecca] gets better at doing this to Flora, the kids don't have that control. They're not voluntarily giving up that driver's seat, they're being pushed aside and pushed into some pleasant memory, none of which is real, and the kids know on some level isn't real, in order to keep them quiet," Flanagan explains. "The end game is to reduce these children's souls basically into a size that is so small that they'll just forever exist in these little memories. And these ghosts can just walk out in their bodies and have another chance at life. So, that's the very long version of what took us six months to figure out in the writers' room as we tried to break it."

Of course, as those of us who've seen the whole series already know, this sense of taking over control can also be used for good, which is what points the way toward Bly Manor's ultimate, bittersweet conclusion. We'll have more on that and other aspects of the series from Flanagan very soon on SYFY WIRE.