Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Robin Hood of the river! How archerfish evolved to shoot insects out of the air

The ultimate in biological Super Soaker technology.

The oldest surviving written account of Robin Hood is preserved at Cambridge University and dates to sometime in the 15th century. The character, and the story surrounding him, has remained one of the most enduring stories in the Western canon, inspiring ongoing adaptations to stage and screen, including the 2010 adaptation starring Russell Crowe. Despite the legend’s endurance, there’s a lot we don’t know about Robin of Locksley. Varying accounts describe him as being of noble birth while others describe him as a servant or farmer. Moreover, it’s unclear if Hood was a real person or a fictional invention. What is clear, is that he was a master of the bow, able to fire an arrow at a target with pinpoint accuracy, even in less-than-ideal conditions.

We may never know the truth about Robin Hood, but the mysteries surrounding his sharpshooting animal counterpart, the archerfish, are finally being uncovered, thanks to a recent study published in the journal Integrative Organismal Biology. Matthew Girard, from the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and Biodiversity Institute at the University of Kansas, and colleagues, looked at the anatomy and genetics of various archerfishes to uncover how they became the crack shots they are today.

“We know a lot about their behavior, they’re often studied for their intelligence, but very little was known about who they are related to and how this mechanism evolved,” Girard told SYFY WIRE.

In the popular parlance, all archerfish are referred to under a single banner, not unlike Robin’s merry men, but that doesn’t do justice to the significant genetic and anatomical variation present in these animals. When the study began, researchers weren’t even sure if all so-called archerfish were even capable of firing water shots like their most well-known compatriots.

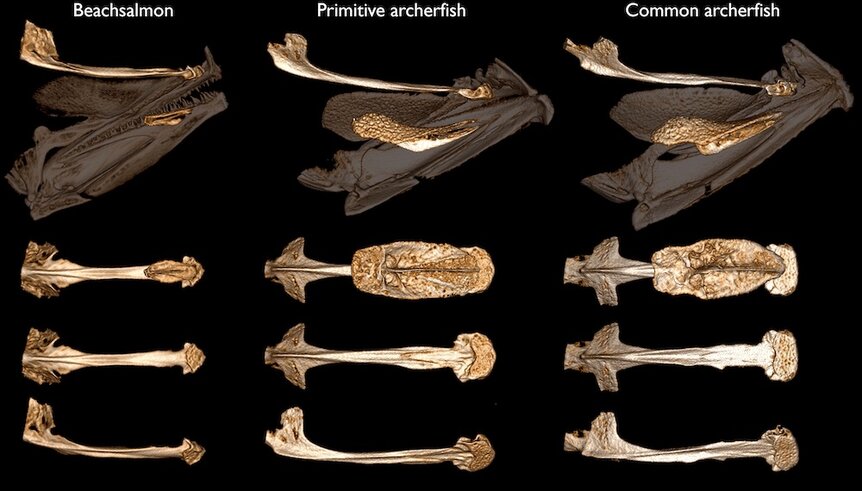

Solving that mystery required an analysis of how archerfish manage to be such impressive marksmen in the first place. Historically, there have been two prevailing hypotheses about the physiological processes enabling them to knock flying insects out of the air and into their waiting maws. The first, known as the blow-pipe hypothesis, suggests that specially structured bones allow them to rapidly push water through a groove between the bones, like water through a straw. The second, known as the pressure tank hypothesis, suggests that the fish build up pressure inside their bodies before firing water out of valves behind the lips. According to the study, the anatomy of all known archerfish supports the blow-pipe method.

“They have this tongue bone with an unusual shape. It has a keel on the bottom and a big mound on top. It lies underneath the roof of the mouth which has this groove in it. They move the tongue bone up and it makes this little hole between the two bones. By doing this rapidly, water comes out the front of the mouth,” Girard said.

That’s a complex set of structures which would need to be present in order for archerfish to adapt this hunting behavior. Looking at related species revealed they might have an ancestor of their nearest relative to thank for doing the foundational evolutionary construction for their mouth-mounted crossbows.

“We know that the ancestor to archerfishes was eating hard bodied things. Their called beachsalmon, they’re this Australian and New Guinean intertidal marine animal. They can’t spit, their tongues are really small, but there are a lot of structures that are really similar between them and archerfishes,” Girard said.

Tracing the evolution backward, somewhere between the beachsalmon and what researchers call primitive archerfish, their mouth parts were slightly modified, allowing the shooting behavior to emerge. Precisely when that happened in the evolutionary record isn’t known, but it likely happened tens of millions of years ago. Physical adaptations are one thing, but they don’t necessarily amount to much without the cognitive software to identify, target, and knock a meal out of the air.

“They’re very smart. They’ve been shown to be able to count and they can adjust the shot based on distance. They have these bowling ball eyes that are able to look through the air-water interface and they have the brain power to correct for refraction. They’re really remarkable,” Girard said.

Robin Hood might have been able to redistribute wealth and take down a corrupt police force in medieval England, but we’re not sure even he could fire an arrow from underwater and hit a bird on the wing. No one is that good, save for the archerfish.