Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Our throats are simpler than a chimp's, and that might be why we can talk

Simpler voice boxes allow for more complex speech.

King Kong works as a story, not because Kong is a giant monster but because he is so human. The characters of the various films learn too late that the threat they were fighting was imagined and they’d lost, through fear, the opportunity to commune with a being other than themselves. Of course, even if things had gone differently, Kong wouldn’t have been able to communicate with anyone in the usual human way, through spoken words.

It was once thought that only humans were capable of meaningful communication. At first blush, all of the other animals are simply making noises without any higher meaning attached to them. We now know that not to be case. Some birds, like Alex the parrot, appear to have exhibited an at least rudimentary ability to understand and communicate with human handlers. Certainly, dolphins have complex languages and may even be capable of learning the languages of closely related species. And, of course, there are the other great apes. There is some debate about whether or not apes like Koko were truly capable of learning and understanding sign language, but there’s less debate about whether or not non-human apes have language. Indeed, recently, gorillas were observed creating what could be interpreted as a new word specifically for a new situation.

Even if we accept the premise that Koko and other non-human apes like her were simply mimicking their handlers, we’re left to wonder why they didn’t do so vocally as opposed to with their hands. A new study carried out by an international team of researchers and published in the journal Science may hold at least a part of the answer. An examination of primate vocal anatomy suggests the ability to produce complex vocalizations might have at least as much to do with what’s going on inside our throats as what’s going on inside our heads.

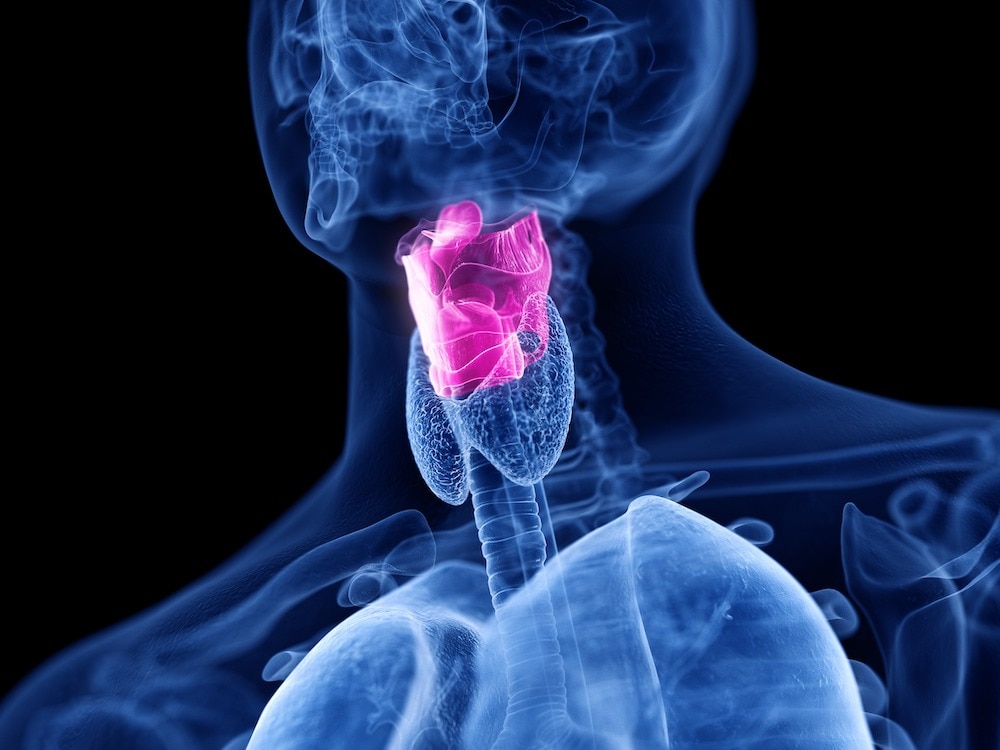

Researchers looked at the voice boxes of various primate species and compared them to what we know about our own. We might have expected to find a more complicated setup inside our own throats, allowing for the comparatively complex array of sounds we’re able to create. However, the team found precisely the opposite. Human vocal anatomy is relatively simple as compared to our closest living relatives and it’s that simplicity which appears to allow us to create the range of complex and stable sounds necessary for vocal communication.

We and other mammals produce vocalizations by pushing air through the larynges. That air then causes the vocal tissues to vibrate and make sounds. In humans, we have only two folds which we call the vocal cords. Other mammals, including chimpanzees and other primates, have more.

The team used chimpanzee cadavers donated by local zoos to get a close look at what’s going on inside the voice box. Scientists removed the vocal structures and blew air through them while filming with a high-speed camera to see what might be happening inside the body when they vocalize. They then took that data and used computer modeling to create a virtual voice box of both humans and non-human primates.

When similar levels of air were pushed through the virtual voice boxes, scientists found that the additional tissues present in non-human primates caused the vocalizations to be chaotic, whereas the simplified voice box of a human was more controllable.

Researchers believe this might be the result of an evolutionary trade-off. The voice box of a non-human primate allows them to produce sounds loudly and across a wide range of frequencies but without the stability humans enjoy. It seems that you send simple messages widely or complex ones more intimately, but not both.

As the need for more complex communication arose in our own ancestors, we might have been more willing to forego volume and range in favor of complexity in language, and our throats changed to suit those changing needs.

All told, it might be a good thing that Koko and the other signing primates never made an effort to communicate with their voices. If they had, we might have been subjected to a chaotic nightmare of a voice which would keep us up at night. It’s a welcome reminder that sometimes when communicating, less is more.