Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

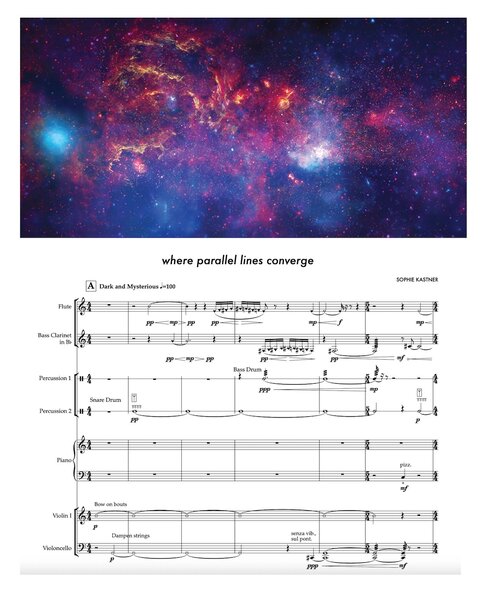

Listen to the Music at the Heart of the Milky Way

The universe has been broadcasting for billions of years and we're learning to tune in.

It’s no secret that animals make music, but they don’t usually hold singing competitions and perform popular songs. At least not outside of the animated family film Sing (streaming now on Peacock). Still, we like to imagine that they would if they only knew it was an option.

Humans will find music anywhere. We hear it in the songs of birds and whales, in the wind whistling through the trees, in the waves crashing against the rocks. We've even managed to record the sounds of a single bacterium bouncing on a graphene drum. And if we can’t find music, we’ll make it ourselves with animal skins pulled taught over wooden barrels, perfectly polished and curved brass, or the signals arriving from deep space. That last one is the result of years of hard work from a collective of scientists and artists working to translate astronomical data into music.

Exploring the Universe Through Touch and Sound

When we look out at the night sky with our naked eyes, faint visible light is all that we can see, but the universe holds so much more. Telescopes on the ground and in space capture visible light but they also pick up infrared light, X-rays, gamma rays, and light from the radio part of the electromagnetic spectrum, all of which are invisible to us. Basically, if it radiates, we’ve got a telescope for it.

RELATED: This is What a Black Hole Sounds Like

Telescopes like Hubble and the JWST deliver their observations in the form of digital data broadcast back to Earth. Once recovered, professional and amateur astronomers translate that data into visible images, converting all of those x-rays, gamma rays, infrared light, and radio waves into something we can experience. Most of the time, data is converted into visual images like the ones you’re used to seeing from Hubble and JWST. Over the last several years, however, scientists and artists at the Chandra X-Ray Center have been experimenting with other ways to experience the universe.

The Chandra X-Ray Center previously created a 3D modeling and 3D printing project. Rather than the flat 2D images we’re used to seeing, they’ve modeled astronomical images in three dimensions, allowing you to move through their layers and explore distant locales more fully. And there are 3D printing files available so that you can enjoy a tiny fledgling star or a violently exploding supernova at home.

When the world went into quarantine at the beginning of 2020, scientists and artists at the project had to shift gears toward something that was wholly digital and could be completed remotely. They needed something they didn’t have to touch, and that something turned out to be sound.

A Musical Melody Co-Written by a Human Musician and the Milky Way Galaxy

Since 2020, the Chandra X-Ray Center has been collaborating with System Sounds to build the Sonification Project, an effort to translate astronomical data into sounds. With a few years’ worth of translated data, the project has moved into its next phase, working with musical composer Sophie Kastner to convert those raw astronomical sounds into beautiful music a human musician (or musicians) could play.

RELATED: NASA’s Latest Cosmic Images Color Space with the Brightest Crayons in the Box

As a first stab, Kastner focused on a relatively small region roughly 400 light-years across at the center of our own Milky Way galaxy. However, there is so much data coming back from Chandra that the resulting music is a jumbled mess. It requires the deft ear of a talented musician to make sense of. Rather than attempting to play all of the data, Kastner chose bits and pieces, highlighting certain parts of the galactic center. The resulting song is called “Where Parallel Lines Converge.”

“I like to think of it as creating short vignettes of the data and approaching it almost as if I was writing a film score for the image,” Kastner said, in a statement. “I wanted to draw listener’s attention to smaller events in the greater data set.”

In the same way that visual artists have created painting, drawings, and other visual interpretations of astronomical data, now musicians can create sonic artworks using the same information. In addition to the artistic value of the work, scientists might be able to make new discoveries or better grapple with the complexities of the cosmos by experiencing it with as many senses – visual, aural, tactile – as possible. It seems that universes and people are similar in that way; the best way to understand someone or something is to listen.

Catch the musical misadventures of a whole bunch of cute animals in Sing, streaming now on Peacock.