Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

New study: Climate change is making hurricanes more destructive

Global warming is a global emergency. It's not just that the world is getting hotter; our climate is a very complex system with a lot of interacting parts, so as carbon dioxide traps ever more heat from the Sun, it's throwing everything off kilter. Some of the ways our climate is changing are obvious (ocean acidification, extreme weather, oceans warming, sea level rise) but others are more subtle.

Take, for example, hurricanes.

Climate change doesn't increase the number of hurricanes overall (the reason hurricanes form is complex and climate change plays into that — for example, warmer water feeds hurricanes more energy, but atmospheric wind shear tends to cut them off at the top, making it hard for convection to really get going — but it doesn't appear to change the total number that form), but climate models have shown that there should be a moderate intensification of hurricanes overall in the North Atlantic, and also that the most powerful hurricanes should become more frequent and even more powerful.

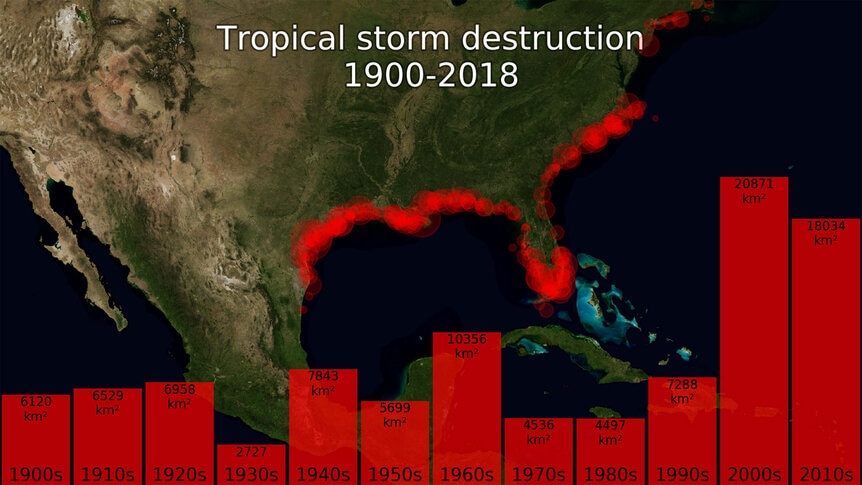

That second bit has been shown pretty clearly in recent years; when you look at the most powerful hurricanes they are clearly growing in number and power themselves. But are hurricanes in general doing more damage? That's been harder to pin down.

A new study, though, shows that the models are correct: Hurricanes are indeed doing more damage to coastal populations in the United States. Moreover, scientists can put a number on it: The frequency of the most damaging hurricanes more than tripled per century.

Holy yikes.

This has been a point of contention for a while now. It's hard to measure how much damage is being done. For one thing, hurricanes don't happen terribly often, so the numbers for your statistics are a bit small. For another, how much damage they do depends on where they hit. And third, wealth has increased over the years, so you have to figure that into the calculations as well; if coastline property gets more developed and expensive, then hurricanes can do more expensive damage and take more lives even without getting stronger.

This is why the researchers did something clever: They normalized the data using something they called the "equivalent area of total destruction." To explain that, I need to break it down a little.

First, normalization is a technique used by scientists to try to get different datasets on the same footing so they can be compared. For example, you could ask how much money is spent state by state on, say, soda. You would probably find that California and New York spend way more on it than Montana. But of course, those states have a lot more people! So you divide your numbers by the number of people in each state to normalize them (in this case, giving the per capita spending on soda), and then you can analyze the data better, since they can now be directly compared.

Normalizing data taken in different ways or across a long time baseline is a very well understood way to be able to compare lots of different data. What's important is how you do it, and to make sure it isn't introducing even more biases to your data instead of removing them.

In the past, hurricane researchers have tried to normalize things by accounting for inflation, per capita wealth, population density, and more. Another group of researchers added wealth concentration to that, accounting for differences between urban and rural impacts — this is called the actual-to-potential-loss ratio (ALPR), which means how much damage there was compared to how much there could have been, and that depends on wealth in a given region.

So the way this new research normalizes this data is to take that ALPR and add another factor: the area over which that wealth is distributed. They call this the area-of-total-destruction, or ATD. In a way, this is asking, "Given the financial loss from a hurricane, how large an area would have to be totally destroyed to account for it?" In this way, they take out of the equations factors like wealth distribution so that comparing a hit to, say, Miami can be more directly compared to one that hits up the coast where there may not be as high a density of people and property.

When the scientists did this, some interesting things happened. For one thing, damage correlates better statistically with hurricane wind strength, which makes sense. The trends they measure are also less noisy than previous ones, making it easier to see any trends that exist.

What they found is what I reported above: Hurricane damage is rapidly increasing over time, and this correlates strongly with climate change, as predicted by models.

Mind you, this work is incredibly important due to the scale of hurricane damage. The very first couple of lines of the paper state "Hurricanes are the costliest natural disasters in the US. The damage costs from Hurricane Katrina have been estimated to be $125 billon, which was 1% of GDP for the entire US in 2005." Wow.

I'll note that they have not included the fact that buildings are getting stronger now than they were in the past. Think about that: Adding that in would make this trend stronger, because all things being equal, stronger buildings means less damage. So if you're seeing even more damage, it must be due to the hurricanes themselves.

This is bad news, obviously, since it means things are getting worse. But it's also extremely useful news, because it means we have another tool to assess what global warming is doing to our planet.

I don't think this will have an impact on climate science denial, at least not right away. Over the years, denial has changed. At first it was a simple denial of the facts: That we're dumping more carbon dioxide into the air, that the Earth is warming, that this is affecting weather patterns, hurricanes and so on. These arguments are still used by troglodytic deniers, but it's not as common as it once was.

Craftier deniers have changed their argument, though, saying that more CO2 is good for plants, or using subtle arguments like hurricanes haven't been doing more damage over time. That's a favorite of the oft-quoted Roger Pielke Jr, for example. Even before these new results his analyses have been shown by climatologists to be wrong, as well as his conclusions that climate change doesn't play a role in hurricane damage.

Now, though we have yet another way to show this argument is false. These new results show, if you'll excuse the metaphor, which way the winds are blowing. It's clear that hurricanes are affected by climate change. The stronger ones are getting stronger, the stronger ones are getting more frequent and now we can state more confidently that, in the North Atlantic at least, they are doing more damage because the climate is changing.

And while this work won't shut up climate science deniers — nothing ever will, even if they all lived on an island submerged by rising sea levels — it gives science communicators and policy makers another tool to use to make sure people understand what we're doing to our environment.

Information is power, if it's wielded correctly. And it's important to note that this new study directly affects wealthier people. I expect many if not the majority of these folks would be politically conservative, so this new study may help in influencing them. That would be an important step in changing what's really driving this: Politics. Were it not for that — and, of course the billions of dollars funneled into politics by the fossil fuel industry — we could have started working on actual solutions to this global climate emergency years ago. Decades.

Keep that in mind when elections roll around next year. Does someone on the ballot deny the science of climate change? Maybe their opponent would do a better job on truly fixing this crisis.

[My thanks to climatologist Michael E. Mann for his gracious help answering my questions about this paper.]