Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

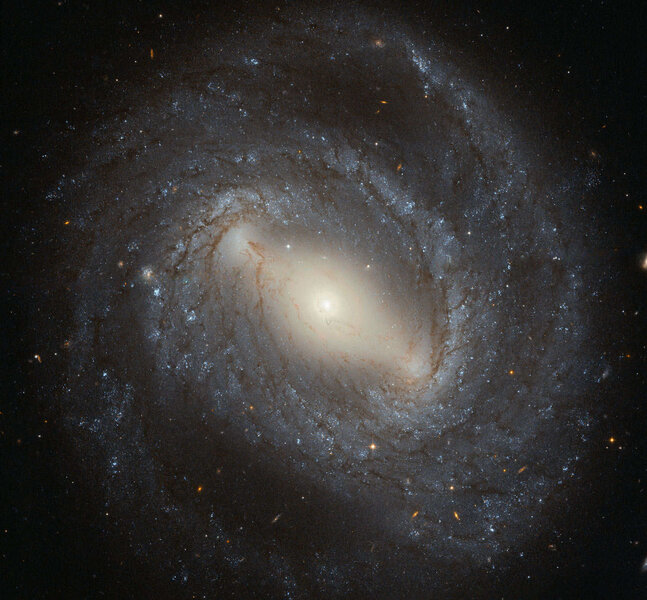

NGC 4394: A gorgeous galaxy with a built-in bar

I really, really wish that one day I could throw out a spectacular image of a sprawling spiral galaxy and just say, "Here. HERE. LOOK AT IT. LOOK AT ITTTTT!"

But I can't. I just can't.

So first, yes, here. HERE. LOOK AT ITTTT.

Oof. Wow. So what is it?

That is a Hubble Space Telescope image of NGC 4394, a galaxy about 55 million light years from Earth. It's most likely a member of the Virgo Cluster, the nearest large cluster of galaxies with very roughly 1,500 member galaxies— our own Milky Way, the galaxy we live in, belongs to a small group called the Local Group, which itself belongs to the Virgo Cluster. So we're neighbors! Kinda. More like we live in different suburbs of the same big city.

It's a gorgeous example of a nearly face-on spiral, one we see from a high angle. Galaxies like this are most generally disk galaxies, comprised of a wide circular disk of stars, gas, and dust, in this case about 60,000 light years wide, half the size of the Milky Way. The disk itself features broad spiral arms, a defining characteristic, but the origin and behavior of which is still debated.

It's also a barred spiral, referring to the huge lozenge or Tic-Tac-shaped structure going across its middle. Half of all spirals have this feature, including our own. They form due to the spread out nature of the mass in a galaxy.

In our solar system the Sun dominates the mass, and therefore the gravity. But a galaxy has its mass spread out over tens of thousands of light years, and that changes the way the stars and other objects orbit. The disk can become unstable, matter can clump up, and structures like spirals and bars can form.

The bar rotates around and its gravity affects material outside it, drawing in gas to the center of the galaxy, acting like a cosmic slide, funneling it down. In many cases this feeds star formation, since stars are born from such material. Also, all big galaxies have a supermassive black hole in their centers, and all this material can fall into it, forming a disk that gets infernally hot and glows fiercely.

In fact, NGC 4394 has evidence of ionized gas in its core, which means gas got so hot some of its elements like oxygen and nitrogen were stripped of some of their electrons. It's rather mild in this case, so we say NGC 4394 has a LINER: a low-ionization nuclear emission-line region. It's not clear if this is from its black hole nibbling on the infalling matter or if it has such prodigious star formation that massive, luminous stars are blasting ultraviolet radiation at the gas, ionizing it. LINERs are very common in barred spiral galaxies.

Bars tend to be made of older stars, and there's a big color difference between the bar and the spiral arms; the former is redder and the latter bluer. Spiral arms are where stars are actively born, and the most massive ones (which are the brightest) are blue. They also die young, leaving redder stars behind, so when we see that ruddy glow in a galaxy we know it's a place where stars haven't been born in a long time.

It's hard to tell in this image but the very center of the galaxy is quite bright in blue light. Either lots of stars are forming there, or again the black hole is feeding; either will shine blue.

I love the filigree-like dust lanes in the arms and bar. This is from grains of rocky (silicaceous) or sooty (carbonaceous) material expelled by dying stars, and is opaque to visible light if the material is dense enough. It might only have a few million molecules per cubic centimeter, but strewn over hundreds of trillions of kilometers that's enough junk in space to block the light from stars behind it. I love how it adds to the beauty.

One cool thing about this image is that it was created using images from two different Hubble cameras: The Wide Field Planetary Camera 2 and the Advanced Camera for Surveys. WFPC2 was installed on Hubble in 1993, and ACS in 2002.

I'll note that this image was assembled by my pal Judy Schmidt, aka SpaceGeck/Geckzilla, and has a variation of it on her Flickr page. ACS has a gap between its two detector chips, and she used the older WFPC2 images to fill in the gap. Clever. The images of NGC 4394 from each camera were taken in 2001 and 2006, and like every Hubble image were archived and can be used later, so older observations are still useful when later ones are taken.

So yes, it's a beautiful image, certainly. But there's science behind it, knowledge hard-won after decades of study, and puzzles as yet left to solve. And that's why it's so hard for me to just toss up an image like this and say BEHOLD.