Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Now well beyond Pluto, New Horizons sees its next target

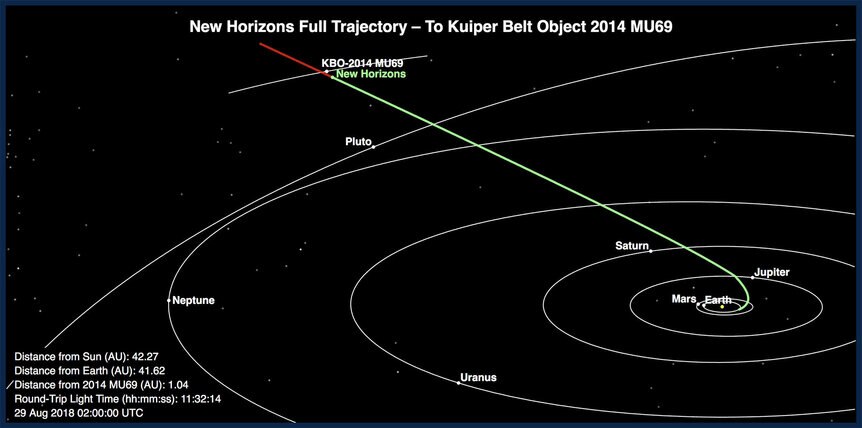

On January 1, 2019, the New Horizons spacecraft — which skimmed the surface of Pluto in July of 2015 and returned all those awesome images — will pass by its next target: the Kuiper Belt Object (or KBO) 2014 MU69.

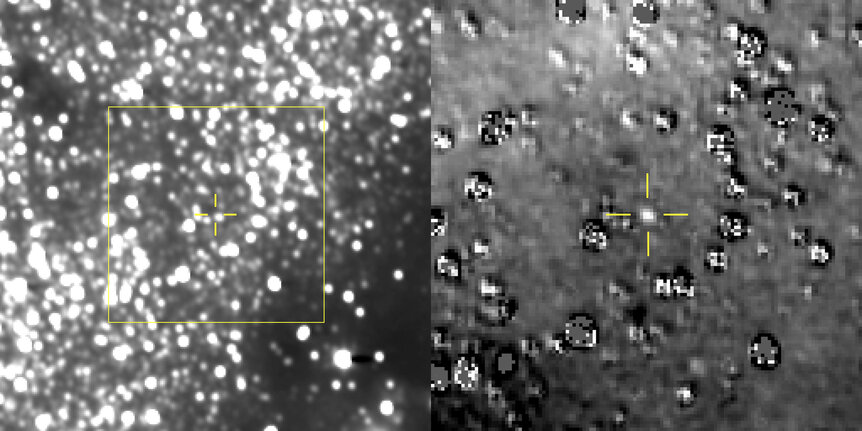

On August 16, 2018, the spacecraft aimed its wide-field camera at MU69 and took 48 half-minute exposures. When processed, the mission team was happily surprised to see the iceball pop right out in the final image!

That’s pretty cool. On the left is the stacked image created using all four dozen images. As you can see, there are a lot of stars! The crosshairs mark where they expected MU69 to be. Unfortunately, it’s just to the upper left of a much brighter star.

However, a little image processing took care of that. On the right is the final product, where the star images have been subtracted away using a template made from images New Horizons took in 2017. This removes the brighter stars, leaving behind the glow from MU69.

Even cooler, the spacecraft was over 150 million kilometers away from MU69 when it took these images; that’s about the same distance as the Earth from the Sun. It’s incredible to think that the probe will cover that distance in just four months! It’s screaming out of the solar system at about 14 kilometers per second, fast enough to cross the diameter of Earth in just 15 minutes. It’s moving.

At the time of this image, MU69 was about 6.5 billion kilometers from the Sun (and 6.37 billion km from Earth). That’s also about a 1.5 billion km farther out than Pluto. This is a substantially long way away.

We don’t know much about MU69. Nicknamed Ultima Thule in a vote held by the New Horizons team, the object was only discovered in 2014 using Hubble Space Telescope. Even before the Pluto flyby, scientists knew that once New Horizons sailed past the icy world it would be in the Kuiper Belt, the part of the solar system beyond Neptune populated by rocky iceballs, essentially huge comet nuclei, some of which are quite large (the biggest known (besides Pluto), Eris, is roughly 2,300 km across; smaller than the Moon but still decently big).

Knowing the amount of maneuvering fuel left on New Horizons, scientists could determine how big a volume of space the probe could explore, a cone that widened with distance. Hubble was aimed into that part of the sky and found MU69, which was added as a new target.

We learned a lot more in July 2017 when MU69 passed directly in front of a star as seen from Earth. By observing it from different locations on Earth, this event, called an occultation, can reveal the shape of the object. Astronomers were pleasantly surprised to find that maybe MU69 isn’t one object, but might be two! It looks like it has two fairly equally sized lobes (like the comet 67/P Chuyurmov-Gerasimenko), or might even be two objects in orbit around each other. Another occultation just occurred earlier in August 2018, too, which may help nail down the shape.

That’s important to help plan observations as New Horizons flies past. The more we know about it now, the better it’ll help when the time comes. The flyby won’t take long! At the speed the spacecraft is going, the entire close pass will last a few hours, so the mission planners will be packing in as much science as they can. The flyby will be close: The plan is for it to pass a mere 3,500 km away! That’s threading a very tiny needle given how far the spacecraft has already traveled.

After the encounter, it’ll take a while to get the data back from the probe; it’s a long way, and the transmitter isn’t powerful. The data transfer rate is about 1 kilobit per second. Yes, kilobit. Each image takes the better part of an hour to get sent back to Earth! So don’t get too impatient on New Year’s Day 2019. It’ll take time before we start to see the goods.

So stay tuned. More data will be coming as New Horizons nears its target, and for the first time in human history we’ll see a Kuiper Belt Object in situ and up close and very personal indeed.