Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Saturn's moon Enceladus shows fresh ice: More geysers on the tiny iceworld?

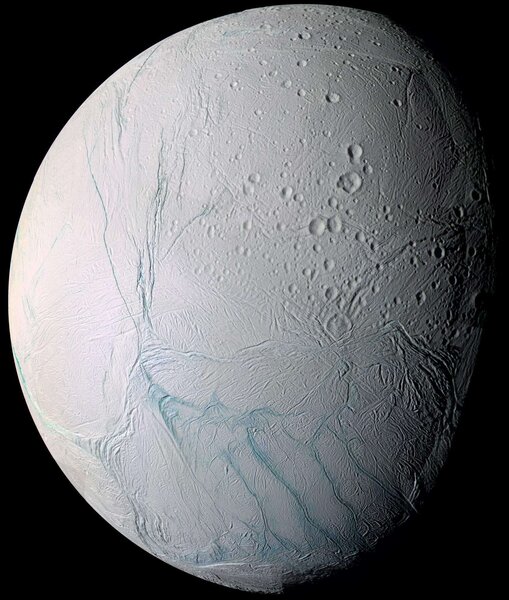

Saturn's icy moon Enceladus has one of the most amazing features in all the solar system: a series of huge geysers erupting from cracks near its south pole, water ice blasting into space due to huge pressures under the surface. There's a subsurface ocean there under a thick ice shell, and possibly a rocky core that makes the water salty. Conditions under the surface are actually quite hospitable for the presence of life.

Unsurprisingly, this makes planetary scientists extremely interested in the tiny 500 km wide moon (about the same size as my home state of Colorado). New results from old observations made by the Cassini spacecraft mission, which orbited Saturn for 13 years and made close flybys of Enceladus 22 times, now show that some ice in the northern hemisphere also shows signs of being fresh (on geological timescales, at least). This may be due to weak geysers, or it could be from water forced up through cracks in the moon's outer ice shell.

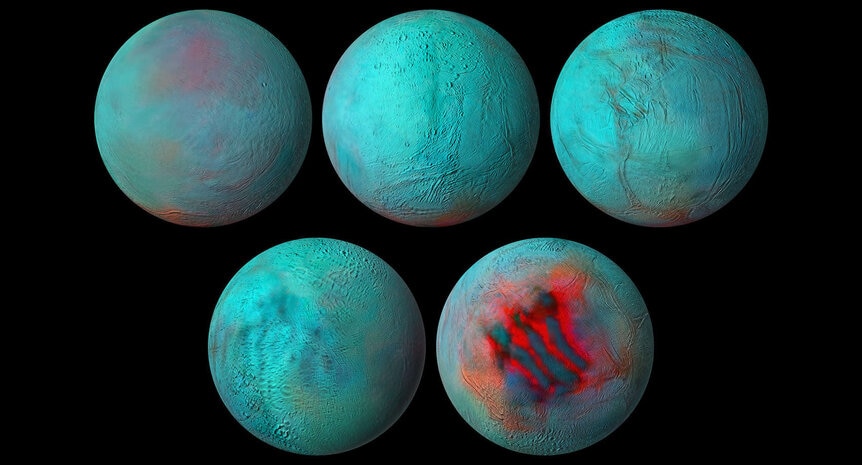

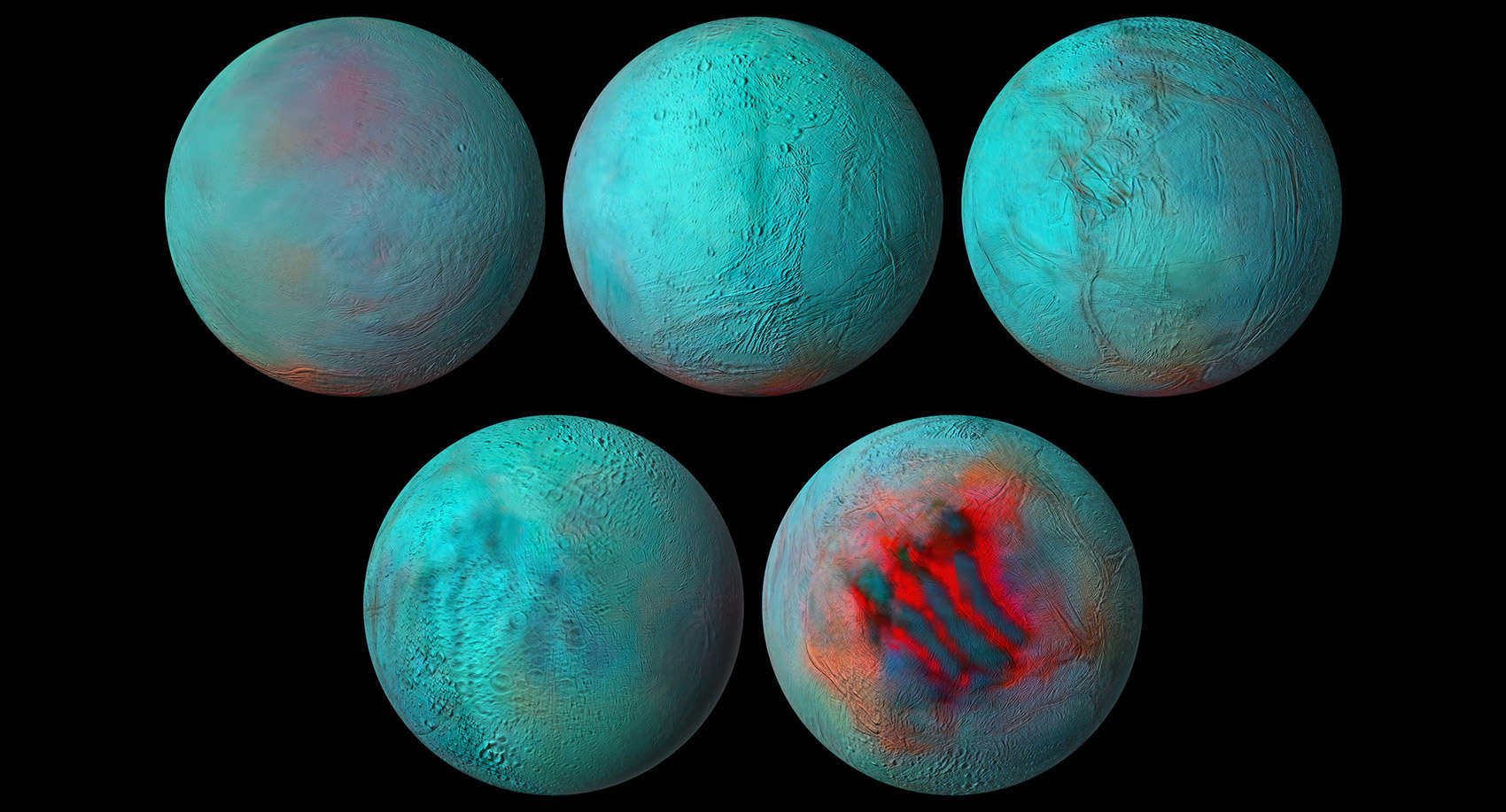

The new maps were made using Cassini's Visual and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (VIMS), which took spectra of the moon's surface in visible and infrared light. A spectrometer breaks the light up from an object into individual colors (or wavelengths). Some material, like water ice, absorbs light at very specific wavelengths, and in a spectrum will reveal itself via dips in brightness (called absorption lines) at those wavelengths.

VIMS took a lot of spectra of Enceladus over time, mapping the entire surface. However, the brightness seen by the instrument depends on the angle at which it looked at the moon, as well as the angle of the Sun in the sky. That means you can't just compare one spectrum taken at one time with a second taken at some other time; you have to correct for these changes in angles.

It's a complex task, but that's just what the planetary scientists did in the new work, creating a global map that corrects for these issues.

The maps shown here use different colors to represent different parts of the infrared spectrum. Due to the differences between fresh and old ice, fresh ice appears red in the images. The south pole is obvious: The geysers erupt from a series of deep cracks in the surface called sulci (Latin for "furrows" or "grooves"; the singular is sulcus). There are a series of them, long parallel grooves nicknamed "tiger stripes," though to me it looks more like deep gashes left by a tiger's claws.

The geysers there deposit fresh ice, so that entire area appears red in the images. But there's a large region centered at 30° north and 90° west that also sports relatively fresh ice. This was hinted at in earlier work, but shows up clearly here.

There's an interactive version you can play with, too; click and drag to move it around.

Fresh ice almost certainly means water from below the surface has made its way up. No geysers were seen from this region in any of the Cassini passes, so either there aren't any there or they're very weak. Interestingly, that area is directly over where some "hot spots" in the sea floor are predicted to be, so it's possible that the warmer water rises and slowly leaks up onto the surface there.

That would be even more exciting than geysers, in my mind, because it would be evidence that the sea floor under the subsurface ocean is active geologically. It's thought that the core of Enceladus could be warm enough top create such hot spots, with boiling hot mineral-laden materials flowing up from there, just like black smoker vents on Earth's ocean bottoms. Life thrives in these spots on Earth, so that would make the idea of life on (under!) Enceladus perhaps a bit more likely.

The Cassini mission ended in 2017 when the spacecraft was purposefully dropped into Saturn, specifically to prevent it from possibly impacting a moon and contaminating it. The incredible observations it took are all back on Earth, stored on computers, still ready to be analyzed or re-analyzed, processed by scientists who have new ideas for the old data. In this case, they may reveal a new place to look for life, or at least a place to look for interesting geological processes.

It's a great legacy for fantastic mission.