Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Keep cool with real stillsuits made of nylon and silver, no electronics needed

It won't protect you from Shai-Hulud but it will keep you cool on a hike.

Whether you’re working on Arrakis or in an office building, regulating your body temperature is crucial for remaining comfortable, productive, and alive. At least a couple of those things are probably on your to-do list for today.

A significant portion of global energy demand and greenhouse gas emissions are spent on temperature regulation, and that portion is expected to increase as average global temperatures continue to rise. With that in mind, scientists have set to work developing novel fabrics capable of assisting in temperature regulation without the use of electronics.

A recent paper by Po-Chun Hsu from the Thomas Lord Department of Mechanical Engineering and Material Science at Duke University, and colleagues, describes a newly developed textile for venting body heat automatically and on demand. Their findings were published in the journal Science Advances.

By combining layers of nylon and silver, they were able to craft a material which bends in the presence of water vapor. Importantly, the bending action occurs naturally through physics, requiring no additional energy expense. Using this material, the team can create garments with vents which open automatically when a wearer sweats and close again once they cool off.

“It needs to be able to absorb water vapor and expand to create the length asymmetry for bending,” Hsu told SYFY WIRE. “Many water-absorbing materials can do this, but nylon is perhaps the most cost-effective one that is already widely used.”

The nylon was paired with silver for its ability to reflect mid-infrared radiation, though researchers noted that other metals do this as well. Aluminum worked just as well and would be more cost-effective in the event these fabrics become commercially available.

In order to coat the nylon, silver was bombarded with an electron beam which converted it to a gaseous state. The gaseous silver was then allowed to condense on the nylon, leaving a uniform coating on the fabric. The process is known as electron beam evaporation.

“On the side facing the skin, nylon absorbs more water vapor and wants to expand more than the other side facing the environment,” Hsu said. “This creates mechanical strain inside the nylon, and it has to curve to accommodate the strain. When they body stops sweating, the water escapes from the nylon and it flattens again.”

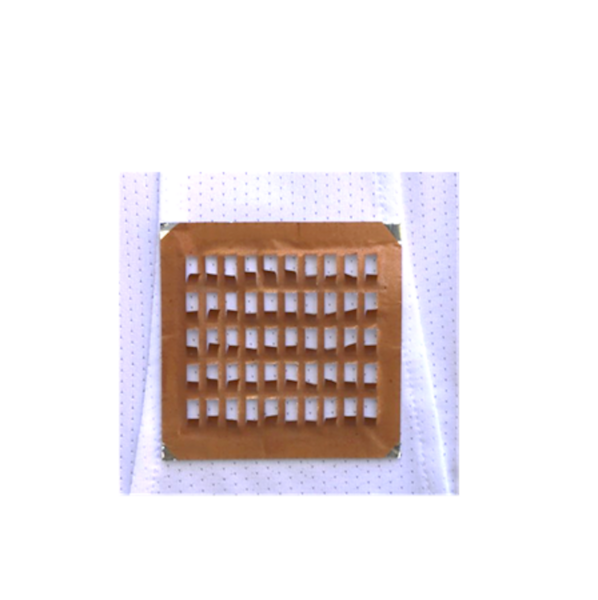

Because nylon isn’t very thick it isn’t suitable for crafting entire garments for a range of environmental conditions. Instead, researchers believe their material would be useful as patches added to pre-existing garments constructed of other materials.

For instance, say you’re out on a winter hike in a heavy coat and the strain of the exercise causes you to overheat. Today you might need to take your coat off to let yourself cool. Before long, the sweat on your body and in your underlayers cools, and suddenly you’re freezing. You find yourself stuck in a cycle, putting your coat on and taking it off.

With these metalized nylon patches deployed at strategic locations along your coat, that venting and cooling action would happen automatically as the temperature inside your coat changes. In essence, instead of taking off your whole coat, the vents would take off tiny parts of the garment as needed without you ever having to think about it. You’d keep the heat in when you need it and let it out when it becomes too much. Moreover, this material should work in a wide range of temperatures.

“Nylon should be able to maintain its hygroscopic expansion behavior as long as it can maintain its shape at high temperature and there is enough water vapor at low temperature,” Hsu said. “Human perspiration always exists, so water vapor source is not a concern even at low temperatures. At very high temperatures, say 100 degrees Celsius, nylon can start to soften and is no longer responsive to water vapor, but those temperatures are way beyond common scenarios.”

Even Arrakis didn’t get that hot. As long as we can reclaim the lost moisture, garments patched with silver-coated nylon could be the last thing you ever need to add to your interplanetary wardrobe.