Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Scientists encounter odd ecosystem living under 2,500 feet of solid Antarctic ice

Proving that there's still a mysterious segment of Earth's biosphere we haven't yet encountered, scientists with the British Antarctic Survey recently engaged in polar ice core drilling for sediment samples on Antarctica's Filchner-Ronne Ice Shelf and accidentally found an entire ecosystem living on a seafloor boulder.

What's remarkable about this amazing find is that these sea creatures, which included unknown species of sponges and stalked marine animals, should not have been able to survive at nearly a mile below the ice shelf surface in total darkness with no discernable food supply... yet there they were!

According to Wired, to conduct the planned experiments studying the history of the half-mile-thick ice shelf, geologist James Smith of the British Antarctic Survey spent three months in sub-zero weather camped in a tent while subsisting on an uninspiring menu of freeze-dried food.

After repeated attempts to collect sediments down through the 3,000-foot drilled hole in the ice using a sampling device attached to a GoPro camera, Smith and his colleagues were unsuccessful. After regrouping and scanning the footage, though, they realized that their equipment was smacking against a giant rock sitting an additional 1,300 feet below, instead of on the actual seafloor.

“It’s like, bloody hell!” Smith says. “It's just one big boulder in the middle of a relatively flat seafloor. It’s not as if the seafloor is littered with these things.”

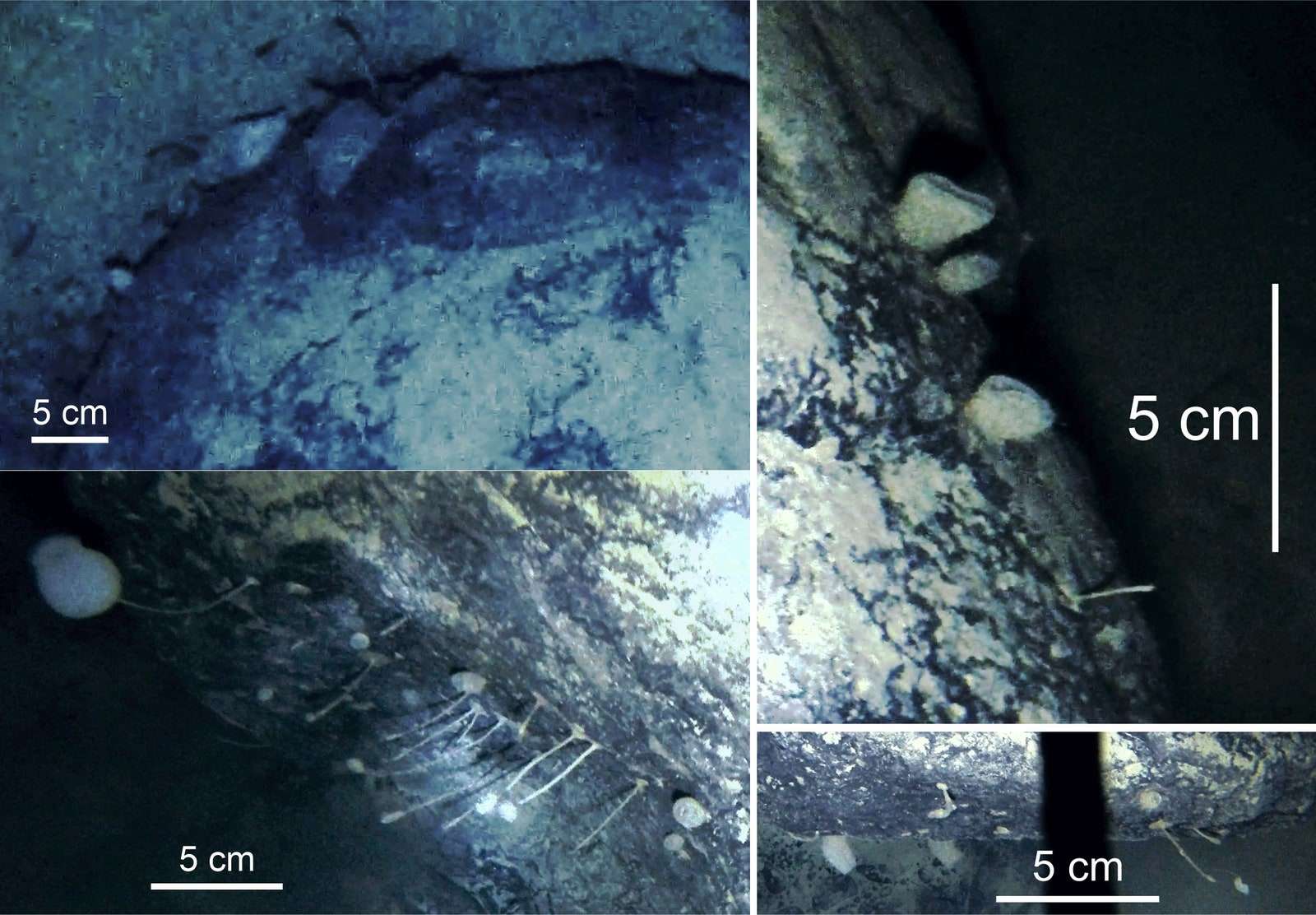

British Antarctic Survey biologist Huw Griffiths inspected the recovered video images later and was stunned at what he observed on this huge hunk of stone. A layer of bacteria known as a microbial mat covered the humongous boulder, which was home to alien-looking sponges, an assortment of strange stalked animals, cylindrical sponges, and wispy filaments believed to be a type of animal called a hydroid.

This unexpected haven lies 160 miles from sunlight, which is the place where the ice shelf ends and open ocean starts. This is literally hundreds of miles from the closest reliable food source, where daylight would normally nourish an actual healthy ecosystem.

“It's not the most exciting-looking rock—if you don't know where it is,” says Griffiths, lead author of a new paper published in the online journal Frontiers in Marine Science. "Since you now do know, then it means your jaw may be somewhere near the floor right about now."

Animals that live "sessile" (stuck in one spot) on the deep sea floor, either in partial or zero daylight, must rely on a steady supply of food in the form of “marine snow.” All living entities calling aquatic environments their home eventually perish and sink to the bottom where they decompose into tidbits and particles which become a floating buffet that eventually accumulates on even the most remote of seaflooors.

“The worst thing in a place where there's not much food, and it's very sporadic, is to be something that's glued to the spot,” adds Griffiths.

To answer a portion of the mystery, Grffiths and Smith theorize that this little dark world might exist due to an anomaly in the normal type of "marine snow" nutritional currents. Here in this alien environment, it appears that the seaborne smorgasbord operates in a horizontal manner rather than the traditional vertical.

By studying current charts surrounding the official drill site, the British researchers concluded that there are abundant food sources between 390 and 930 miles away. A stream of organic material drifting amid these currents might be enough to feed these hungry creatures, even though it seems almost inconceivable when considering the vast distance.

More theories will be further explored by the British Antarctic Survey, but Rich Mooi, an expert on Antarctic sea life at the California Academy of Sciences, insists it might not be that farfetched when understanding how complex Antarctic waters are the engine that runs Earth's oceanic currents.

“It sinks to the sea bottom and pushes water outward, radiating outward from the Antarctic,” says Mooi. “And these currents are actually the germ of many — if not almost all of — the current systems on the planet.”