Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

So, um, does anyone remember where we put that supermassive black hole?

You'd think a black hole with the mass of a decent-sized galaxy would be easy to find. But then, you're not looking for the one in the center of a galaxy in Abell 2261.

Abell 2261 is a ridiculously huge cluster of galaxies about 2.7 billion light years away from us. It has thousands of galaxies in it, and astronomers measure its total stellar content to equal the mass of a quadrillion (1015) Suns.

So yeah, it's a beefy cluster.

Like most big clusters, it has a big galaxy sitting in its center. It doesn't have an official name, but astronomers call it Abell 2261 BCG, for Brightest Cluster Galaxy. In general, galaxies in the centers of clusters are the biggest and brightest; they're literally at the bottom of the cluster's gravity well, and everything falls into them. Mergers with smaller galaxies are common, so the central galaxy usually grows huge. In this case, the central galaxy is over a million light years across, hugely dwarfing our own Milky Way (which is about 120,000 light years wide).

We also know that every big galaxy has a supermassive black hole in its core. The ones in the centers of central galaxies tend to be really huge as well, for the same reason their host galaxies are: They're gourmands, feasting on gas and stars and everything else that falls into the cluster center.

Looking at various parameters of Abell 2261 BCG, astronomers estimate it should have a central black hole weighing in at a soul-crushing 10 billion times the mass of the Sun. That's a big black hole; compare it to the one in the center of our Milky Way galaxy, called Sgr A*: It has a mass of about 4 million times the Sun, making the one in Abell 2261 about 2,500 times bigger. Yikes.

Except… there's no evidence that black is, um, there.

Embarrassing. How do you miss a monster like that? Usually, again because the center of a cluster is like the drain in a particularly large sink, so much stuff should be falling in that it piles up into a disk around the black hole. That disk is enormous and incredibly hot. The material in it glows so fiercely it can outshine entire galaxies and be visible clear across the Universe.

Hiding something like that is hard.

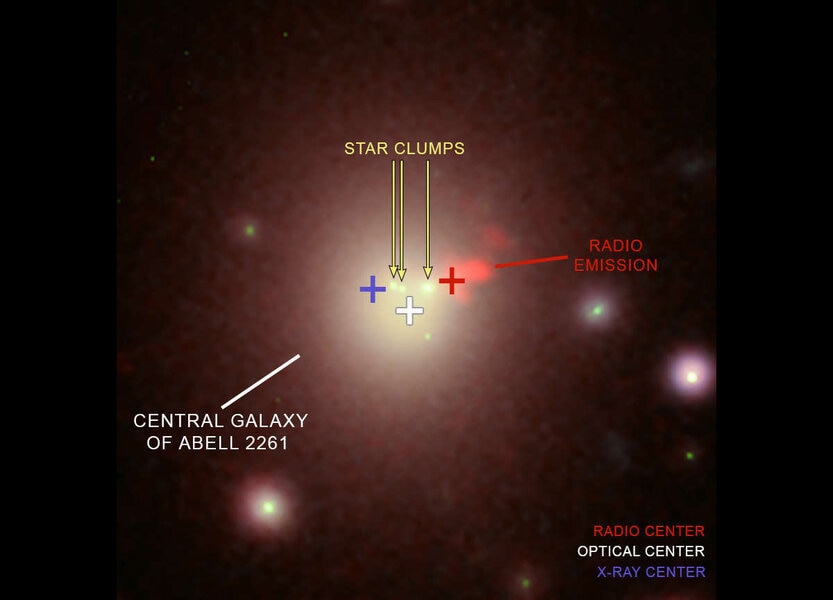

But, Abell 2261 BCG is an odd galaxy. The images of it in visible light show that the core of the galaxy is unusually large and has some other unusual features. Plus, it's not centered in the galaxy itself! That's really weird. The off-center nature is seen in both the distribution of stars and hot gas in the galaxy.

That happens sometimes after a merger; when a big galaxy eats a smaller one things can get off-kilter. That leads to an interesting idea: Maybe the black hole ate too big a meal and got tossed out of the galaxy's center.

If the central galaxy merged with another galaxy that also had a supermassive black hole, that second one would fall toward the center, toward the bigger black hole. Over a few billion years the two could get so close they orbited each other, and then they would eventually merge, eating each other, forming a single bigger black hole and releasing a truly vast amount of energy in gravitational waves.

That blast of energy can sometimes be off-center. We're talking staggering energies here, like converting thousands of times the mass of the Sun into pure energy. If that explosion is even a little bit off-center, a little bit asymmetric, it can give a huge kick to the resulting black hole, flinging it away from the galactic core.

Wondering if that's what happened in Abell 2261 BCG, astronomers looked at the core carefully. Intriguingly, there are four very bright clusters of stars there, as well as a spot that's bright in radio waves. Could one of those five objects be the site of the missing black hole? Maybe it dragged those stars with it, or hit some gas and caused it to emit radio waves.

If true, the black hole should be a pretty strong source of X-rays. So astronomers used the Chandra X-ray Observatory to look at Abell 2261 BCG for a long time — 100,000 seconds, nearly 28 hours — and added that observation to an older one of 35,000 seconds (nearly 10 hours) to get a very deep image of the core of the galaxy.

And what they found was… Nothing. No hint of a black hole in any of those five spots, and not in the center of the galaxy itself self either. They were able to eliminate several other possible locations, too.

That's bizarre. Either the black hole doesn't exist — which is so unlikely it can be dismissed — or it's just not eating enough material to glow in X-rays. That's pretty unlikely as well. Now, our local supermassive black hole, Sgr A*, isn't glowing much in X-rays because its not feeding right now, so in principle a quiescent black hole like that is possible.

But this one would be a huge black hole in the center of a huge galaxy in the center of a huge cluster, and has that enormous mass of ten billion Suns! A black hole like that being quiet is really, really peculiar.

So either way, this is a bona fide grade-A astronomical mystery. The Case of the Missing 20 Undecillion-ton Elephant in the Room.

If the black hole is there (and I think it is), it's not at all clear how to find it. Maybe we need to look at other wavelengths, or make deeper observations, or both. Maybe it really is quiescent, and can't be found. But if that's true, then why?

Sometimes, if you want questions answered, science is frustrating. And even when you do get answers, it just leads to more and more puzzling questions. But the Universe is a pretty strange place. We need to keep asking those questions if we ever want to figure it out.