Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

The origin of teeth: How body scales may have migrated into the mouth

We learned to bite, quite literally by the skin of our teeth.

It is often said that nature is red in tooth and claw — that’s readily apparent from a viewing of Ocean Predators — but that hasn’t always been the case. Life has existed on our planet, in one form or another, for roughly 3.7 billion years, but teeth didn’t arrive on the evolutionary scene until about 500 million years go. That means that for the first 86% of life’s history, nature had to be red in… well, something else.

The origin of teeth has been something of a debate among the paleontological community for some time, the subject of an evidential tug of war between two opposing beginnings. On one side of the debate is the inside-out origin: the idea that teeth evolved independently of external features from inside the mouth, sprouting up more or less where they are today. On the other end is the outside-in origin: the idea that teeth began as external armor which only later migrated into the mouth.

The notion that teeth might have found their beginnings on the surface of the body is both terror-inducing and at odds with our base assumptions, but that doesn’t preclude it from being true. According to a recent study published in the Journal of Anatomy that might be exactly what happened.

Scientists from Penn State Behrend didn’t intend to wade into the dental debate but found themselves trapped in its proverbial jaws while studying the chainsaw-like denticle scales of one of the oceans’ weirdest fish. Sawfish are closely related to modern sharks and rays but differ in one immediately apparent way. The are equipped with dramatically elongated snouts sprouting from their faces, lined with features known as rostral denticles. These sawtooth-like features are modified body scales which the animals use in foraging and defense.

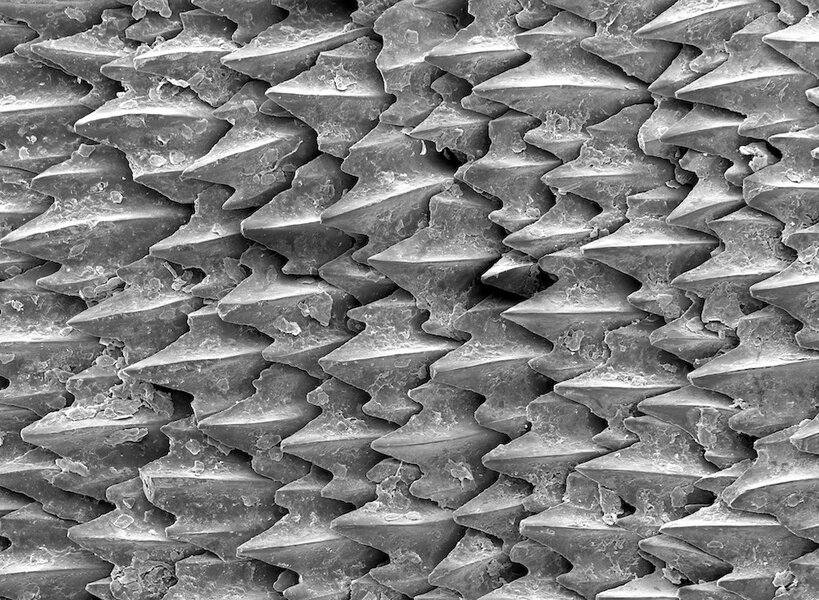

They aren’t true teeth, in fact they’re still pretty far removed from the mouth even in modern sawfish, but they share many of the same characteristics. If you’ve ever had occasion to feel the body surface of a shark or ray, you might have noticed its sandpapery feel. That’s because their bodies are covered in dermal denticles which, when observed close-up, look an awful lot like teeth and are even covered in a substance similar to tooth enamel.

The foundational idea of the outside-in origin of teeth is that these dermal denticles specialized as they migrated closer to the mouth until they eventually became the razor-sharp chomping tools we know and fear today. To date, however, there has been a gap between the external scales and the jaw that we haven’t been able to close. If teeth evolved from dermal denticles, we should expect to see them transitioning to something more tooth-like as they move toward the mouth. That makes the rostral denticles of the sawfish the perfect place to look.

Researchers were studying the fossilized rostral denticles of Ischyrhiza mira, an extinct member of the sawfish family which lived during the Cretaceous, in an effort to characterize its sawtooth scales. As previously mentioned, they weren’t really looking for an answer to the tooth debate when they started and, in fact, they expected them to have a similar structure as the rest of the body scales. But that wasn’t the case.

Measurements taken with an electron microscope revealed that the rostral denticles along the snout were substantially different from other body scales, particularly as it relates to the enameloid coating their surfaces. By comparison, they exhibited an internal structure closer to shark teeth than to other body scales.

The inner workings of the rostral denticles revealed a unique crystalline structure similar to that seen in teeth. This structure allows the denticles to more readily withstand the stresses of feeding, precisely what we’d expect to find if they were on their way to becoming teeth.

It provides a path by which body scales could, over time, evolve into the sorts of structures which might have existed in early teeth. Given the structural similarities between the sawfish’s snout denticles and the teeth of its closest relatives, we’re left to consider two possibilities. Either these scales adapted over time and became teeth, or teeth evolved independently to have very similar features. Convergent evolution among features with similar roles certainly isn’t unheard of, but given the proximity on the body, it seems reasonable that the teeth of fish — and eventually the teeth of humans — got their start as rough body scales which eventually found their way into the mouth.

Sharks, rays, and sawfish were weird and frightening enough before we knew they were basically pure muscle coated in teeth, or that our own teeth are basically holdovers of the ancient scales we have long since lost.