Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

The Milky Way stole a lot of its satellite galaxies from another small galaxy

Big fleas have little fleas upon their backs to bite 'em,

And little fleas have lesser fleas, and so, ad infinitum.

From "Siphonaptera," Augustus de Morgan

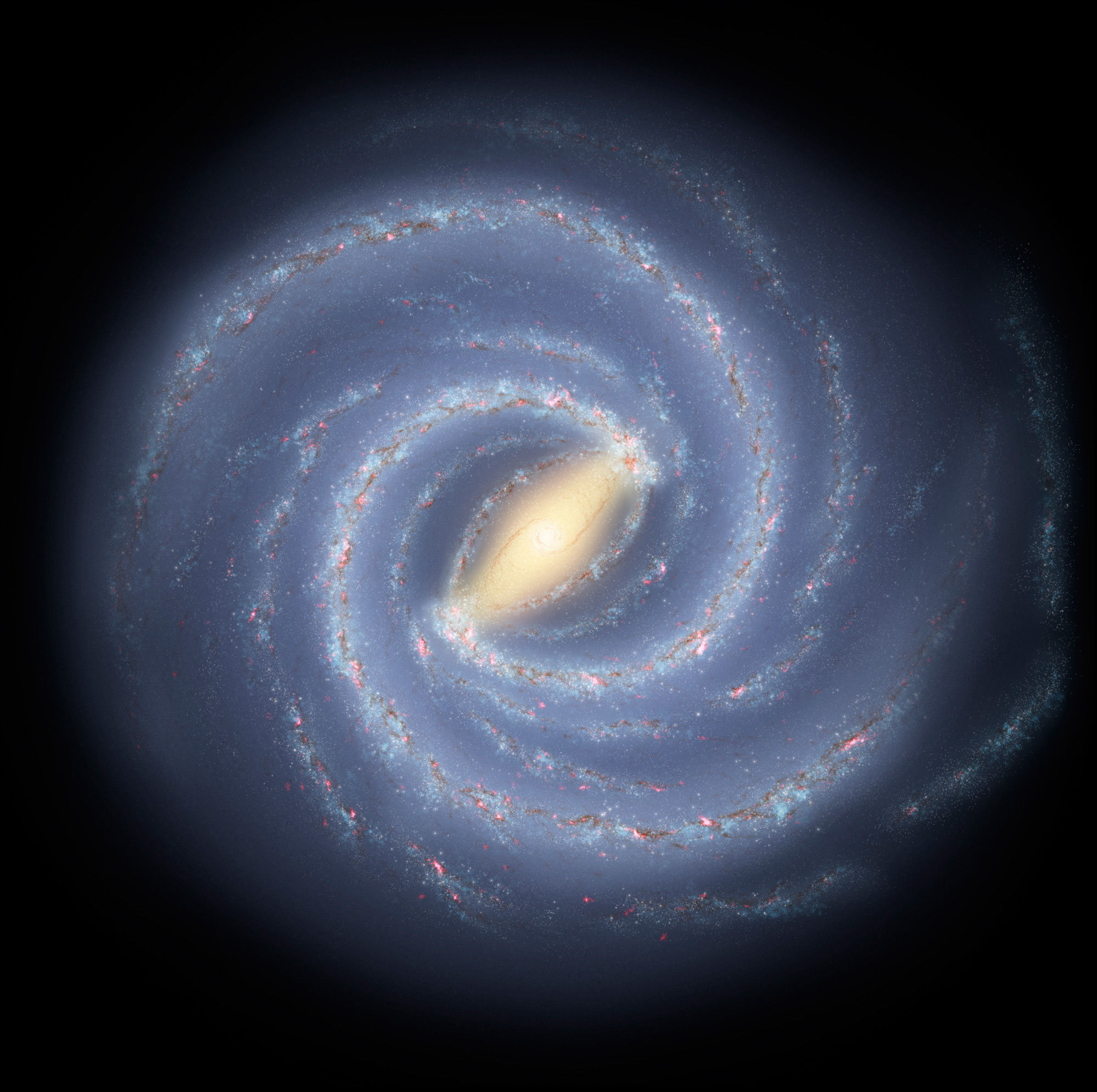

When you look at a big galaxy like the Milky Way, you see it has a lot of components. There's a central bulge of old stars, a flat disk of stars (usually sporting spiral arms) around it, a halo of old stars surrounding that, a dark matter halo which we can't see directly but which has profound gravitational effects due to its huge mass, and a coterie of smaller dwarf galaxies and clusters of stars orbiting it.

It's those last two which have recently come to more attention by astronomers. We think that dark matter clumped together in the early Universe, and 'normal' matter (the stuff that makes up stars and planets and you) was drawn into it gravitationally, forming galaxies. Galaxies themselves wound up getting huge halos of dark matter, including galaxies that are very large (like ours) down to far smaller ones.

In fact, one prediction is that the dark matter halos around galaxies are 'scale invariant,' a fancy term that means that a halo surrounding a big galaxy looks very much like the halo surrounding a smaller one, the only difference being scale. Also, it's predicted that the halos aren’t smooth; instead they can have clumps of dark matter in them, which means these are regions with somewhat more gravity, and so small galaxies may have even smaller galaxies orbiting them.

It's a relatively new idea (I was surprised to read about it; I was unaware of this idea until very recently), but it means that even dwarf galaxies that orbit the Milky Way can themselves have satellite galaxies. Hence the poem at the top of this article.

The Milky Way has dozens of satellite galaxies. The two biggest are the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds (LMC and SMC). For a long time it was thought that these two dwarf galaxies simply orbited the Milky Way, but evidence has been piling up recently that they are actually a binary pair, orbiting each other, and may simply be passing through, swinging by the Milky Way.

A new study combining complex computer simulations and observations of several dwarf galaxies near the Milky Way indicate that these tiny galaxies did not form with our galaxy, as has been thought, but were in fact stolen from the LMC!

Basically, by including the effects of gravity, motion, dark matter, and more, their models showed that four extremely small galaxies (called Carina 2, Carina 3, Horologium 1, and Hydrus 1 — named after the constellations in which they are found) and two somewhat larger ones (the Carina Dwarf and the Fornax Dwarf), were once orbiting the Large Magellanic Cloud, and as it passed the Milky Way the much larger gravity of our galaxy tore the smaller ones away from the LMC, and kept them for its own.

Moreover, their simulations predict that smaller galaxies like the LMC should have more clumps (what they call substructures) in their dark matter halos than big galaxies do. If that’s the case, then there may be many more ultrafaint galaxies out there around the LMC (or stripped away by the Milky Way), given the size and mass of the dark matter halo around it. That’s an interesting prediction, and may be observable as bigger survey telescopes come online. These galaxies are faint — they can be well over 200,000 light years away, and only have a few thousand stars in them. But once discovered, over the years if their motions can be tracked it’s possible they could be more evidence this model of the dark mater halo around the LMC may be collected.

That’s a problem for the future, though; even discovering these dinky galaxies is hard enough. Many of these tiny objects are still being discovered now! In the meantime, work like this is better informing us on how galaxies like our Milky Way formed and grew over time. It's a difficult problem in physics, so these simulations go a long way in helping us figure all that out.

And I have to chuckle a bit at seeing this paper. Last week I wrote about the Andromeda Galaxy, the biggest nearby galaxy to our own, and how it appears to have had a couple of episode of eating (technically, accreting) smaller galaxies that orbited it. The lead author of the work, Dougal Mackey, emailed me and noted that I have a slight misconception about these smaller galaxies.

Globular clusters are tightly packed knots of hundreds of thousands of stars, some so big they have over a million stars. It used to be thought that these formed pretty much as we see them today along with bigger galaxies early on in the Universe, but newer work seems to indicate that some are the cores of bona fide dwarf galaxies that were stripped of their outer regions when passing by really big galaxies (it can be easy to confuse the two). Mackey noted, though, that this is not the case for all globulars, and that some were actually initially orbiting dwarf galaxies and were stolen by the bigger galaxies!

This is almost precisely what I am writing about here with the LMC and Milky Way, so it's a fun coincidence this all happened in the same week. And it makes me very much wonder… I also recently wrote about the remnants of galaxies eaten by the Milky Way in the past. All that's left of them are streams of stars orbiting around our galaxy, though some do have globular clusters associated with them. How many globular clusters around the Milky Way were actually orbiting dwarf galaxies long ago, which then got stolen by our home galaxy?

The more we learn about these objects, the richer their history seems to be compared to what we once thought. I personally find that fascinating. We tend to seek simple solutions to questions and problems, but nature tells us, over and again, that these are rare. Everything, from galaxies down to people, is more complicated then we initially assume. It's a lesson well worth internalizing.