Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Watch a rare transit of Mercury across the Sun on Monday

On Monday (11 November, 2019) a rare and delightful event will occur: a transit of Mercury across the face of the Sun.

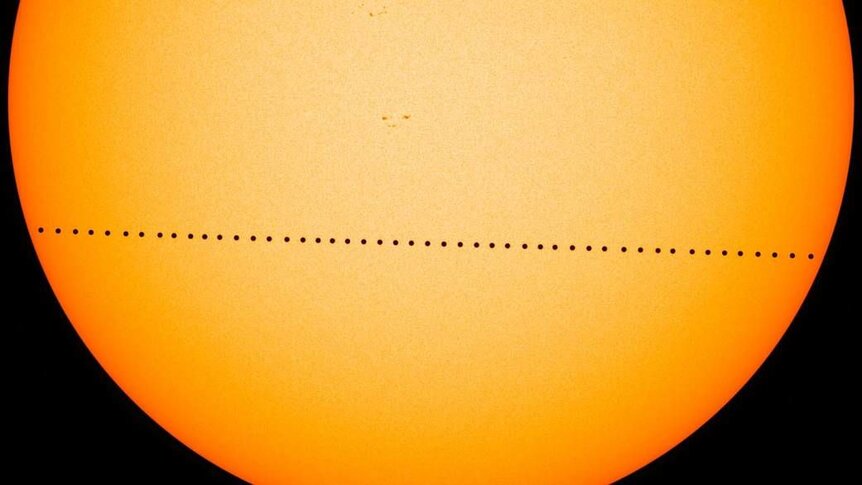

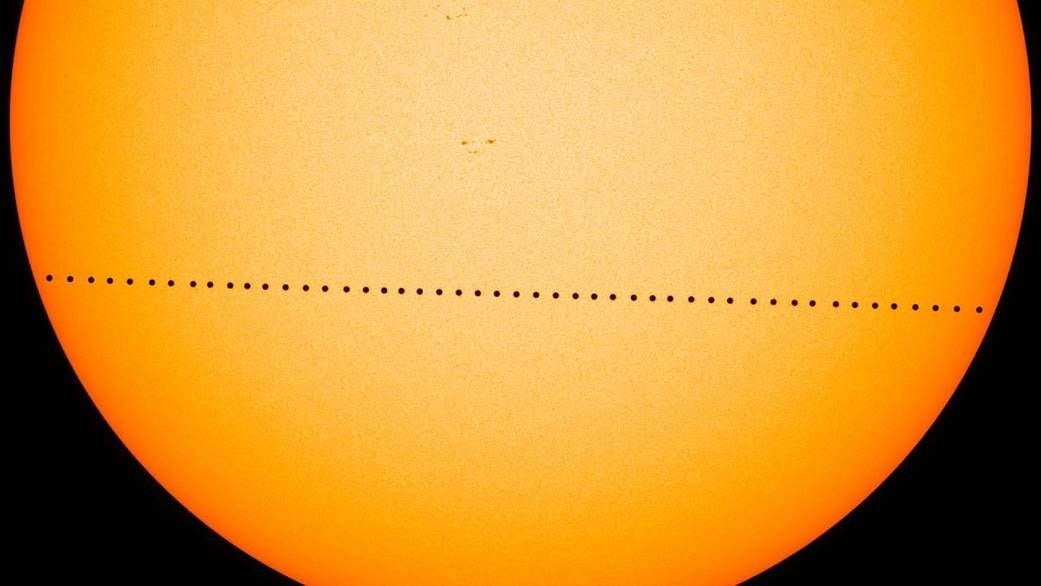

During the transit, Mercury will appear as a tiny black dot slowly making its way across the Sun's disk, taking about five and a half hours to make the journey. This happens only about 13 times per century, so it's relatively uncommon thing to be able to see.

Two quick notes before getting into the meat of this. First, Mercury is pretty small, especially compared to the Sun. You'd need a specially equipped telescope to see this event (or maybe filtered binoculars), and it's slow, so your best bet is to watch it online. I have links to live streams below.

Second, DON'T EVER EVER EVER LOOK AT THE SUN UNLESS YOU KNOW WHAT YOU'RE DOING. ESPECIALLY using astronomical equipment. They amplify the light coming from an object, and we're talking about the Sun here. I'll have details on that below, too.

So what’s the deal?

[Note: I wrote an extensive description of this phenomenon for the 6 May 2016 transit, so that might help to read as well, but remember the timings are all different for this one!]

The planets in the solar system travel around the Sun on orbits that are elliptical (though in most cases they're very close to being circles). For the most part these orbits are all aligned in the same plane, so that if seen "from the side" our solar system looks flat.

But that alignment isn't perfect. Each planet's orbit is tipped a bit relative to each, an angle called the orbital inclination. Because we're biased, we measure this relative to Earth's orbit. Mercury and Venus orbit the Sun closer than Earth does, so if their orbits had 0° inclination we'd see a transit from them roughly once every time they orbit the Sun (when they lap us in their orbit passing between us and the Sun, a point called inferior conjunction; when they pass the Sun on the other side of their orbit [when they're on the far side of the Sun from us] that's called superior conjunction).

But they don't. Venus' orbit is tilted by about 3.4°. From our distance the Sun is only 0.5° in size on the sky, so usually Venus misses the Sun. The same for Mercury, which has a tilt of 7°. What that means is that we see these planets moving back and forth relative to the Sun as they orbit, but when they pass the Sun they move in a line above or below it, so from our perspective they miss.

But sometimes the planets literally align. As I mentioned in an earlier post about orbits, if the orbit of an object is tipped relative to ours, there are two points in its orbit that intersect ours, called the nodes. If Mercury happens to be at a node at inferior conjunction, we can get a transit. This doesn't happen fairly often, only every few years. The last Mercury transit was in 2016, and the next won't be until 2032! So this is a great one to try to see before a bit of a drought.

[Note for the following: Times below are in UTC, so look up what they are in your own time zone. Also, the times may be off by as much as two minutes due to parallax, the change in angle between the Earth, Mercury, and the Sun that depends on your specific location. The TimeAndDate website has a map where you can enter your location and get the local times.]

The transit on Monday starts at about 12:35 UTC, when the edge of Mercury first makes contact with the edge of the Sun (this is called first contact), like a tiny bite taken out of the Sun's edge. It'll grow in size over the next few minutes, until 12:37, when Mercury's entire disk will be inside the Sun's disk (second contact).

Mercury is closest to the Sun's center at 15:20, and it'll be roughly two arcminutes from the center. The Sun is roughly 30 arcminutes across, so that's pretty close! Third contact, when the edge of Mercury touches the edge of the Sun again, is at 18:02, and it finally slips off the disk entirely at 18:04.

For me, in Colorado, the transit starts before sunrise, so the Sun will come up with the transit already in progress. [Correction (8 Nov. 2019): I originally wrote that the transit started two minutes after sunrise; that's what the TimeAndDate site map said, but in reality the transit starts before sunrise and the time it gave me is when Mercury itself becomes visible as it rises with the Sun! That's a confusing way to give out the info, so have a care if you use that site. My thanks to my friend Randall for pointing this out to me.] Oof. I have a telescope equipped with a solar filter, a dark sheet of material that fits over the end and prevents the vast majority of light from getting in. If I'm feeling particularly ambitious I may set that up and take a look. If I do I'll try to get pictures as well! I'll note it tends to be cold in Colorado in November, so no promises.

I have filtered binoculars, too, but Mercury is so small I don't think I can see it with them. Mercury is about 10 arcseconds across, where an arcsecond is 1/60th of an arcminute (which in turn is 1/60th of a degree). That is very wee indeed, so I wouldn't even see it as a dot*. I might try, though, just to be sure. In the meantime hopefully I can keep my 'scope set up to check in every half hour or so.

Again to be very clear, unless you have the proper equipment and some experience here, I strongly urge you not to look at this on your own! You can check to see if any local astronomical clubs or observatories are hosting an event to see it, though. Sky & Telescope has a list of clubs. You can also find a local observatory too.

If you don't have the equipment or a local observatory (or it's just cloudy, or you're on the wrong side of the planet to see it; for the U.S. west coast the Sun rises with Mercury already in transit), there are lots of telescopes that will be streaming it live. Here's a short list:

- The Virtual Telescope Project 2.0

- TimeAndDate.com

- Griffith Observatory

- NASA’s Solar Dynamic Observatory (explanation here)

A web search should provide more, too. Poke around and see what you find.

Websites with more info:

I hope you get a chance to see this, either in person or online! Remember, it'll be 19 years before our orbits align again.

*If this sounds familiar, it's also because this is one way to find exoplanets, planets orbiting other stars. The dip in starlight is small from an exoplanetary transit, and this transit exemplifies that; Mercury will block about 0.0031% of the Sun's light. A distant bird flying in front of the Sun blocks more than that.