Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

We're probably safe from an impact by the asteroid Bennu for another 300 years

Well, some much-needed good news: A new paper has just been published showing that we're pretty safe from an impact by the near-Earth asteroid Bennu until at least the year 2300.

Cool.

Mind you, there's a slight chance of an impact on September 24, 2182, but a) it's only about 0.04%, and 2) that's a long time from now.

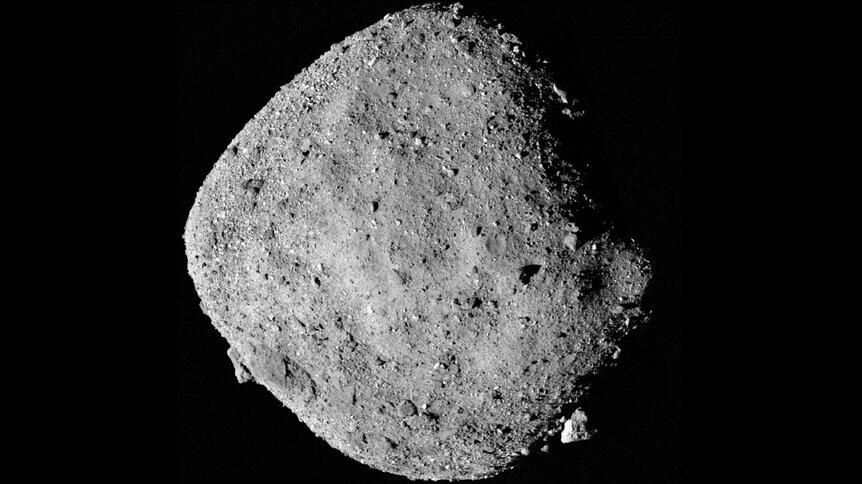

Bennu is a half-kilometer wide asteroid on an orbit that takes it from about 130 to 200 million kilometers from the Sun, one which also crosses very close to the orbit of our own planet. This makes it not only a near-Earth asteroid but also a Potentially Hazardous Asteroid (or PHA), one big enough that should it hit it can do widespread and serious damage.

Because of this, NASA launched the OSIRIS_REx spacecraft to Bennu in 2016 to orbit the tiny rock and take its measure. It mapped the surface, examined its environment, and even nabbed some samples of the asteroid to bring back to Earth, which is expected coincidentally on September 24, 2023.

But it did more than that: It was able to precisely measure the trajectory of Bennu simply by being there, allowing astronomers to get a far better orbital calculation for it than ever before — we can get the spacecraft's exact location over time via telemetry, and use that to determine its orbit. Observing asteroids from Earth means there is some uncertainty in the asteroid's position and velocity, so trying to extrapolate that into the future means its predicted location gets fuzzier with time, and more difficult to determine if it will impact us or not. Getting more precise measurements means a more precise prediction.

An asteroid's orbit is determined by much more than just the gravity of the Sun. The gravity of the planets can affect it, for example, and other asteroids, too. There's a subtle force called the YORP effect as well; sunlight has a very small amount of momentum that pushes on the asteroid in ways difficult to predict. Not only that, but Bennu is spitting rocks in to space (for reasons that are still not clear) and that acts like a very low rocket thrust, changing its orbit. The scientists who looked into the OSIRIS-REx data on Bennu's orbit even looked into whether jamming the spacecraft into the asteroid's surface to get a sample may have changed its trajectory (but, confirming earlier results, they found the effect negligible).

With all these data in hand from the in situ measurements, the scientists extrapolated Bennu's orbit into the future. They found it will pass pretty close to Earth in 2182, and — due to there still being very small uncertainties in the orbit — while they cannot rule out an impact at that date at the 100% level, the odds of it hitting us are a mere 1 in 2,700, which are quite long. I'm happy with that.

Overall, the odds of an impact between now and the year 2300 are about 1 in 1,750 (~0.06%), so again this is a good thing. That's a very small chance, and one I'm not worried over.

It gets better: Even though the chance of an impact is extremely low, it's considered the most dangerous rock out there, tied with (29075) 1950 DA, a 1.1-km-wide asteroid that also poses a pretty small impact risk. So again, this is good; the two most likely impactors we know of out there are still a pretty remote threat.

… that we know of. We still need to keep watching the skies, map out the locations of any PHAs out there, and make sure we understand their orbits and behavior. There may come a day we'll need to do something about them.

For example: Bennu is what we call a rubble pile, a collection of rocks held together by their own gravity. You might think of an asteroid as a single monolithic object, but it has become clear that many smaller ones are in fact bags of rocks. They are extremely porous, and that changes what we might have to do to move them should we find one on an impact trajectory. Hitting it with a space probe, for example, won't work well because instead of moving the asteroid onto a different path, the energy of impact is absorbed by the rocks themselves, moving them around and jostling them together.

Another option — detonating a nuclear weapon near an asteroid — might be a better solution. Not to blow it up; that's a bad idea (now instead of one rock to deal with you may have thousands of somewhat radioactive smaller ones). The purpose of the nuke is to flash heat the surface, which vaporizes the rock there. That hot gas expands rapidly, pushing on the remaining asteroid like a rocket engine, moving into a (hopefully!) safer orbit.

See? We must learn more about asteroids if want to have the ability to prevent them from hitting us. That was a major goal of the OSIRIS-REx mission. And, in fact, Bennu will have a safe close approach of Earth in 2037, near enough that we can ping it with radar and update its orbit as well to make sure we continue to have a decent understanding of it.

I've said this before, and no doubt I'll say it again: Science can literally save humanity, if not the world. Not just with asteroids, but in a whole passel of other areas as well. Just look around; I'm sure you can think of other ways, too.

So we'll keep an eye on Bennu, and 1950 DA, and thousands of other space rocks out there as well. That's Step 1. If we need to take Step 2 to prevent us from going the way of the dinosaurs, then I hope by then we'll have the knowledge we'll need to do so.