Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

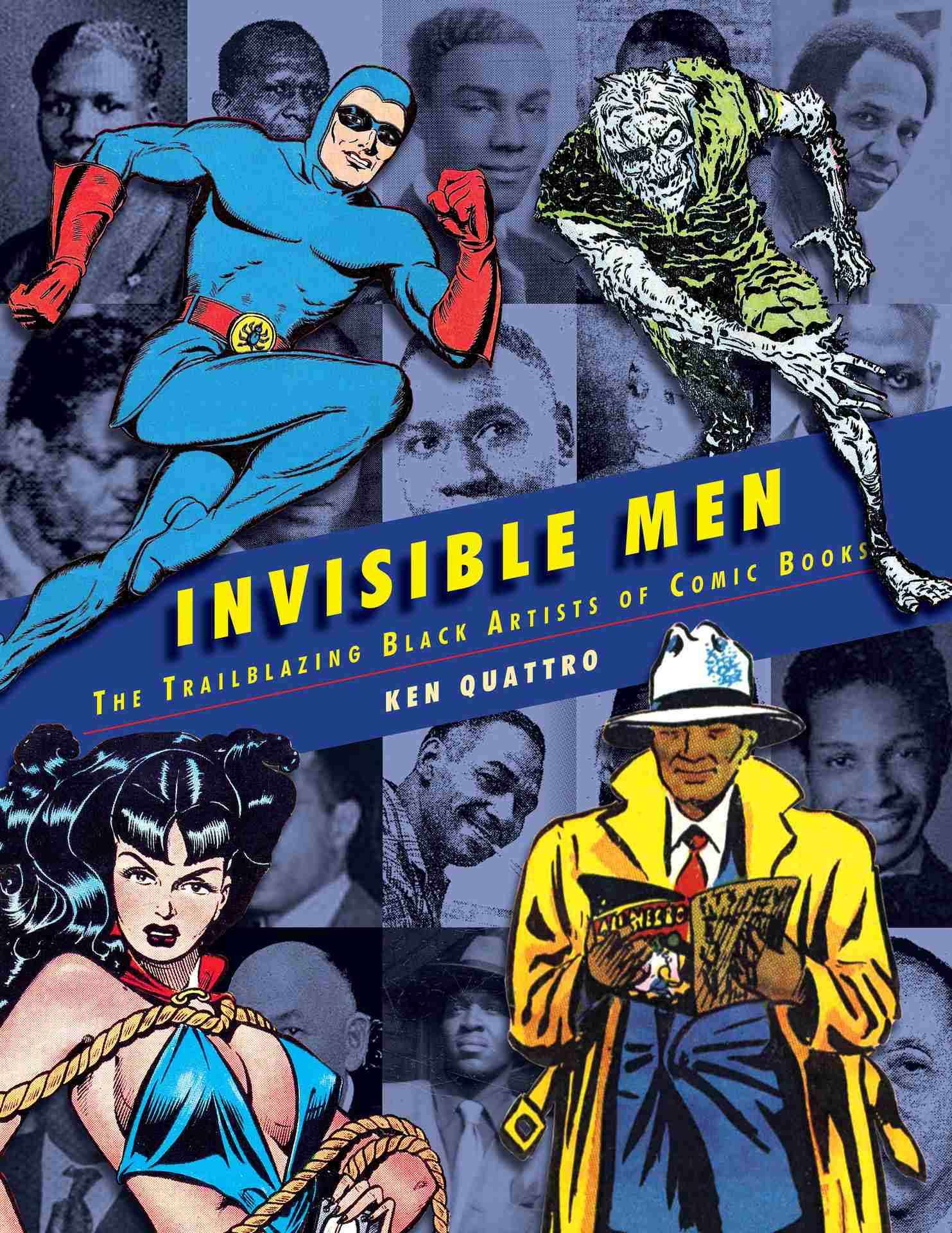

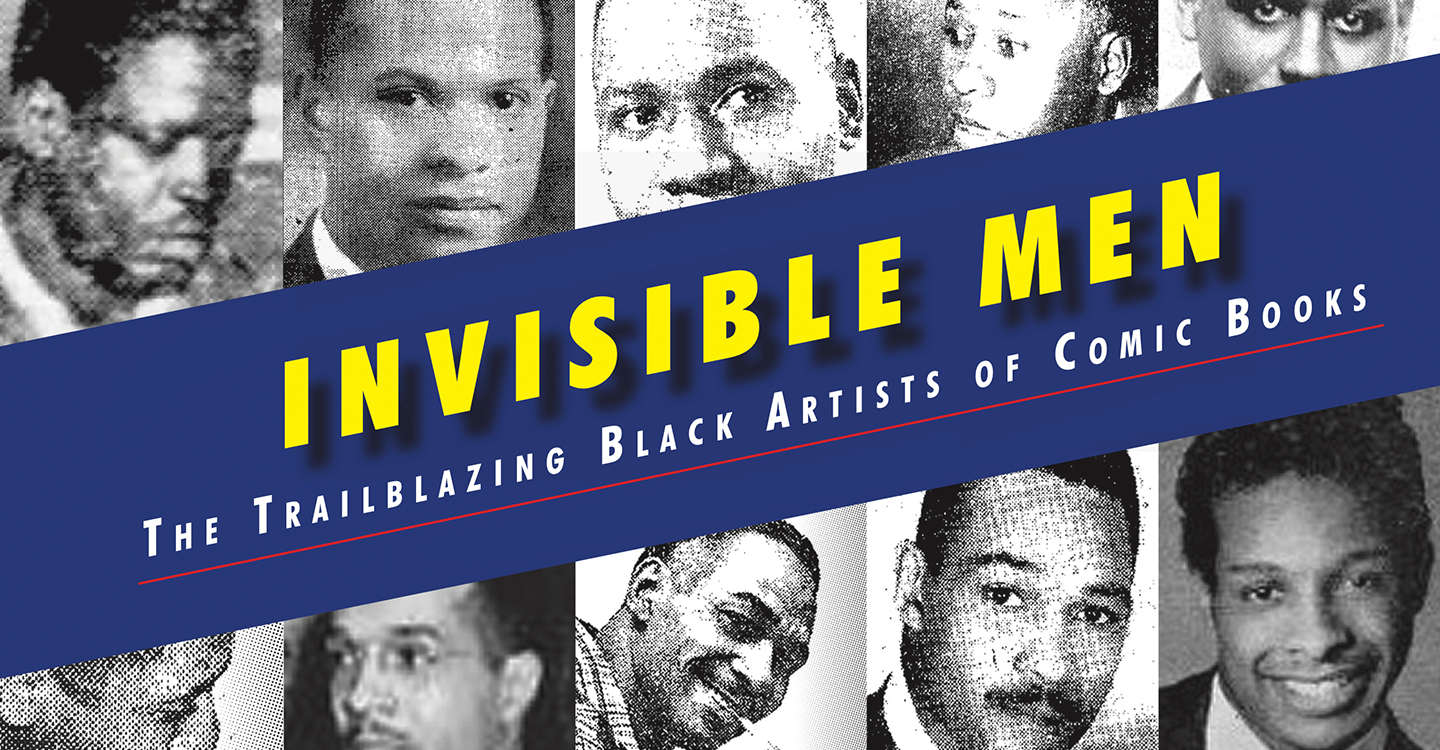

With 'Invisible Men,' Ken Quattro is unearthing the Black, Golden-Age comic artists you never knew existed

In The Souls of Black Folk, written in 1903 by W.E.B. DuBois, the author describes the African American experience as a "Double Consciousness," a psychological condition brought on from living in a world as a Black person "through the eyes of racist white people." Comic historian Ken Quattro was profoundly affected by DuBois' work while he conducted research for IDW's Invisible Men: The Trailblazing Black Artists of Comic Books, his new book chronicling the lives and work of 18 Black men the comic book industry not only forgot but barely acknowledged existed.

Men like Matt Baker, Elmer C. Stoner, Orrin C. Evans, and E. Sims Campbell may not be household names, but they are part of the group introduced in Invisible Men who profoundly affected not just African American visibility in comics, but who also helped shape the comic book industry itself.

Both graphic novel and history book, Invisible Men chronicles Black artists' work during the Golden Age through 1950 (a timeline Quattro created for himself to keep the text under the 300-page limit requested by IDW). So while the book doesn't cover the history of syndicated cartoons or the contributions of artists such as Jackie Ormes or Floyd Norman, it does give a glimpse into a world that very few know to exist: a history the author tells SYFY WIRE he feels has been categorically erased.

In the Golden Age of comics, Black artists and writers quietly contributed to the sequential art medium. "I've been fortunate enough to work alongside modern-day pioneers like Denys Cowan, Dwayne McDuffie, Kyle Baker, and Christopher Priest who have achieved their fair share of 'firsts' and breakthroughs of their own," says writer, director, and Milestone Comics partner and producer Reginald Hudlin of his colleagues.

"[But] even though I have been a dedicated student of comic book history all my life, the vast majority of comic creators whose stories are told in Invisible Men were unknown to me until I read it," Hudlin adds. "Thank goodness for books like this which tell us about 'hidden figures' who overcame incredible obstacles and produced groundbreaking work."

Quattro began research on what would become Invisible Men over two decades ago when he was researching Matt Baker, a talented and successful artist of the '40s and '50s who worked on the likes of Sheena: Queen of the Jungle (Jumbo Comics) and Voodah, a series comic historians consider to feature the first Black comic book hero. As well known as Baker's art was, though, Quattro had a hard time finding anything out about his life.

"In fact, a lot of comics historians at the time thought that [Baker] was the only Black comic artist of the 1940s. Which statistically, makes no sense," Quattro says.

A colleague eventually connected him to artist Samuel Joyner, an African American cartoonist from Philadelphia (whom he credits with being the inspiration for the book) and who had met Baker and many other Black cartoonists of the time. Joyner confirmed Quattro's theory that there were many more artists who deserved recognition.

"Mr. Joyner wrote me back this beautiful, four-page letter that included all these newspaper clippings and photocopies of work by these various Black cartoonists that he had met," Quattro remembers. "Like E. Sims Campbell, Jay Paul Jackson, and Ted Shear. And he had met Matt Baker. I was stunned."

Even with Joyner's immense contribution, researching many of the artists proved difficult. "I would find one line mention here of a person's name and that connected me with somebody else with one crumb would lead to another and one thread that leads to somebody else. It took me 15 years to track all this down," Quattro laments.

"I'm not surprised," cartoonist Keith Knight says of Black artists and creators' work going uncatalogued and unappreciated. No stranger to the historical erasure of African Americans in media, Knight's award-winning comic strip K Chronicles regularly confronts class, race, and politics and was recently adapted to the small screen in Hulu's Woke. "It's sad to say how normal it is to see the contributions of Black people ignored and/or erased. I'm just happy to see these artists finally have a spotlight belatedly shone on them through this book."

Many historians can pore over past newspaper articles and books to recreate people's stories. But that doesn't exactly work in the Black community. Partly because at the turn of the century, The Great Migration saw many southern Black people displaced in northern cities, making citizens' origins challenging to trace. On top of that, Black artists were rarely highlighted in mainstream publications; due to institutionalized racism, most libraries and universities (unless dedicated to that study) didn't preserve Black comics or periodicals. Through his research, Quattro has created one of the only private, comprehensive databases of information on many Black creators from that era.

It helped that Quattro specializes in genealogical research, which proved incredibly useful, especially in Adolph Barreaux, who, born Adolphus Barreaux Gripon in the late 1800s in South Carolina, was considered "mulatto," an antiquated term for someone of mixed Black and white heritage. When he moved North with his aunt and sister to New York, their aunt took advantage of their fair complexions. She changed their biographies, names (dropping Gripon and claiming Poughkeepsie, New York, as their family birthplace), and their ethnicity. That was how Barreaux spent the rest of his life passing as a white man.

"Adolph Barreaux was working for Harry Donenfeld and formed the first comic shop in those days, [Majestic Studios]," Quattro says. "A comic shop was basically just like a big room filled with drawing boards and artists sitting in there cranking out comics as fast as they could."

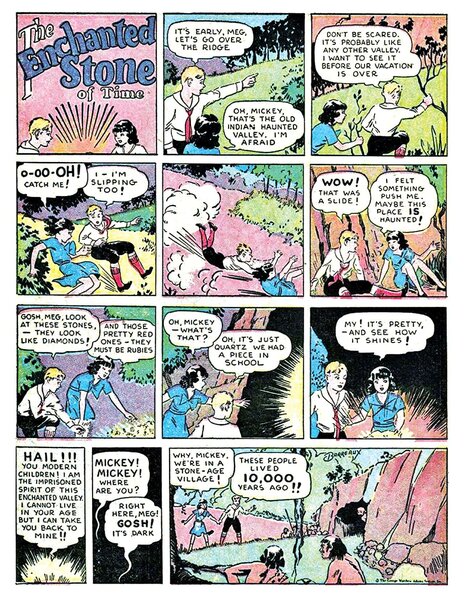

In the Golden Age of comics, quantity over quality ruled the day as shops raced to beat the competition to newsstands. "A lot of Black artists worked with these comic shops. And since they could work from home, many white artists didn't know that Black artists were working with them. They were literally invisible to them," Quattro explains. And because Barreaux's Majestic Studios was the first "comic shop," Quattro credits him for indirectly helping Black artists who were working the comic book business.

"When you talk about Golden Age comics, so much of that work was done by a packaging studio that then sent the strips to a publisher. Individual creativity was frowned upon," Marvel writer Evan Narcisse (Rise of the Black Panther, Marvel's Voices) explains. "They never [even] mentioned Jerry Siegel, Joel Schuster, Joe Simon, or Jack Kirby. That's why sometimes they slipped their names into the work."

He adds: "I knew Black folks were part of this industry. But how Quattro surfaces that talent and some of their contributions at that time is so important."

Elmer Stoner is another artist featured in Invisible Men and, like Barreaux, was of mixed-race descent. Unlike Barreaux, Stoner never concealed his heritage. A classically trained artist, Stoner was well-known in Black circles. "Stoner was very much involved in the Harlem Renaissance. He and his wife were friends with people like Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston," Quattro says. He explains Stoner was important to comic books because, in 1939, he was the first Black artist to work in comic books who did not deny his heritage.

Stoner worked in both Black and white comics, but many Black artists, including Baker, credit Stoner with helping them get paid projects. Quattro describes Stoner as a "conduit," calling him "the most important single Black comic book artist of all time. Because he literally opened the doors for all the rest of them."

Not every artist highlighted in Invisible Men wanted to work for white publications. For instance, the Urban League had created a short run called Negro Heroes about Black historical figures. Then there was Orrin C. Evans, who made All-Negro Comics in Philadelphia. Evans, a highly respected journalist, was the first African American to write mainstream stories for a white newspaper in this country when he wrote for The Philadelphia Record in the 1930s.

"Evans wanted to create a comic book company that just utilized Black artists and writers because it was very obvious [Black people] were never going to get equal representation in comic books," Quattro explains. After the Record folded, Evans realized his dream and created All-Negro Comics in 1947 with his brother, George J. Evans, Jr., an art student, and John Terrelle, an established cartoonist in Black newspapers. Together they created the first issue of All-Negro Comics, which featured "Ace Harlem - Famed Negro Detective." But the book didn't make it past the first issue due to a lack of distribution.

"And when the paper mills found out it was a Black man trying to buy a newsprint to print a comic book, they refused to sell it to him so that he couldn't publish the second issue," Quattro says. "There was such deeply rooted systemic racism they never even had a chance."

Narcisse agrees. "These guys could have been 'Will Eisners.' Or a C.C. Beck, or an Otto Binder; there's so much creativity that died on the vine by virtue of the social, racial stratification and segregation of the day," he says. Invisible Men: the Trailblazing Black Artists of Comic Books is full of these and other stories of people whose work was never recognized.

"It just makes me wonder about how many more are out there. Black writers, painters, illustrators, cartoonists, poets not given their due," Knight muses.

There is indeed so much more that didn't make it into the book that Quattro hopes he can publish a second volume. "I now think at least one semester in every history class in the United States should be told from the Black perspective," he says. "Particularly using Black newspapers and media. It's the first draft of history... Include that in every history class and you'd change a lot of minds in this country."