Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Legion and Lucy in the Sky's Noah Hawley breaks down his characters' breakdowns

In Legion, showrunner Noah Hawley told the feverish, psychedelic-tinged story of a brilliant, damaged mutant, presented from his distorted point of view and tracing his rise (or descent) over the course of nearly 30 hour-long episodes of TV. In his feature debut, Lucy in the Sky, Hawley again sought to bring audiences into the fevered psyche of an extraordinary protagonist in the midst of events that cannot easily be explained.

This time he had just under two hours to tell the story, a crunch for a TV auteur that necessitated the use of all the tools and tricks he'd developed on both Legion and his ongoing FX anthology, Fargo.

Lucy in the Sky is loosely based on the sad, somewhat sordid tale of Lisa Nowak, a NASA astronaut who made headlines in 2007 for driving across the country in a diaper to confront a woman over a former lover. It was the novelty of her profession and undergarments that dominated the headlines; the circumstances of her apparent breakdown largely went ignored in a sensational news cycle not prone to empathy. Hawley fictionalized the story, injecting empathy and new background details to turn it into a "magic realism astronaut movie about a woman's existential crisis," as Hawley explains to SYFY WIRE.

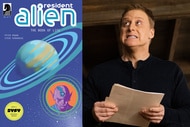

When producer Reese Witherspoon dropped out of the leading role — the astronaut's name was changed to Lucy Cola — to make another season of Big Little Lies, Hawley cast Natalie Portman, who won an Oscar for playing another highly competent and accomplished woman who has an existential crisis in Black Swan. In an ironic twist, Hawley cast Dan Stevens, his leading mutant madman in Legion, as Lucy's very grounded and rational husband, while Jon Hamm plays an irresponsible and heavy-drinking lothario astronaut, and Zazie Beetz is the younger astronaut who is first inspired by and then terrified of Lucy during her breakdown.

Hawley spoke with SYFY WIRE about making Lucy in the Sky and Legion, focusing on the breakdowns his characters frequently face.

**Spoiler Warning: There are spoilers for Lucy in the Sky below**

You made Legion, Natalie starred in Black Swan, so together, you have a lot of experience in characters suffering from mental illness and acting out. How did you come together to approach this one?

I'm very allergic to melodrama in general. I mean, a lot of the time I spent with Natalie, her instinct was also to understate her performance, because Lucy is such a competent problem-solver. She's not someone who's going to fall apart. Even her at her lowest point, I don't think she would characterize what's happening to her as her falling apart. I think she feels like she's trying to solve a problem.

It was very important to me that the audience go on this journey with her and not stand outside of it judging her. It was really critical that we understand what went into those bad choices that she made.

In the scene toward the end of the movie where she confronts Jon Hamm and Zazie, everything she's saying seems completely crazy to them, but everything she's saying to us makes total sense, even though she's not rational in this moment. When she says, "Sometimes there are wasps," well, we've seen how that chrysalis that she's been carrying around hatched and a butterfly didn't come out of it, but wasps came out of it. Everything that she refers to that sounds nonsensical actually makes a lot of sense.

My goal was never to fall into any kind of crazy-lady trope. It was to say what happens when you take a highly functioning, hugely driven person who's never met a problem that they can't solve and you put them into a no-win scenario?

What she does when she's put into this situation in which she's kicked off the next mission, and there's no way that she can solve that problem, is she designs her own mission and she goes on that mission. All the language of it is like synchronized watches, and here's the plan, it's this many miles at this time. She's solving the problem. It's not necessarily healthy, and nor is it necessarily clear exactly what the endgame is, but in her mind she's solving the problem.

We've all watched enough Mission: Impossible movies without ever thinking that Ethan Hunt is a crazy person. I mean, he clearly is. He defies reality at every level. He never gives up. Nothing will ever stop him. They're not really rational choices. I just thought of Lucy in that way, which is, it's only at the moment where she realizes she has a moment of clarity and she realizes just what she's done and how unmoored it is that she has any sense of the fact that she's had a break from reality.

What would you say that moment is?

If you notice, focus is always an element of the film. We use these lenses that were more like the human eye in that they had a kind of central realm of focus, and then they were less focused around that. But then by the time she had driven across the country and we get to the parking garage, literally the image is mostly blurry.

There's a moment in which she's confronted them, she's sort of at her lowest point, that her niece who she told to wait in the car calls out to her. We see the niece and then when we reversed to Lucy, we see Lucy and all the blurriness is gone.

It's just full clarity, and that's the moment that she has clarity. The film is representing her interior state visually, and that's the moment in which she goes, "Oh my God, what have I done?"

You use different aspect ratios throughout the film, as well, switching between scenes and settings. What led to each change?

I mean, most of it is certainly grounded in her subjective experience. The literal, obvious stuff is when she's in space, we're using the whole rectangle. When she comes down to earth and everything feels smaller, the image shrinks. There is a moment, a sequence in the film later, when she learns that John Hamm's character is also having an affair with Zazie's character, in which the box shrinks even further and the sound design becomes much more muffled, because she's so focused on her own thoughts and under so much pressure.

Then there are other elements in it because I'm a playful filmmaker, in which I play with it a little bit. It's not a dogmatic approach, but it is designed primarily to enhance your immersion in the film and to create feelings in you that are the feelings that she's having.

If you allow yourself to go with it, you'll stop noticing it. Obviously, if you resist it or if for whatever reason it bumps you, then you're going to have a much harder time being pulled into the film.

When made Legion, you slowly revealed that David was the villain. You wanted to hint to people, maybe tell them subconsciously, but you had to do it over a much longer period of time. What was the approach there, with episodic TV?

There's a lot of things that I was hugely influenced, both on Legion and then this film, by Sorrentino's film The Great Beauty, in which he mixes reality and memory and dream and fantasy, but he does it without ever really making it clear which one is which.

What happens when you separate images from information is that it forces the audience to create a connection. A big part of editing the film was to try to create an emotional through-line. There wasn't necessarily a literal through-line, so if being back in a test module makes her feel like she's back on a mission, then editorially you go from her in the test module to her back in space and the feeling that that gives her.

Then editorially, the next place that we go is to her on the trampoline with the sparklers and the fireworks, because the feeling of being back in space is that feeling of exhilaration of weightlessness and energy. It's not literal, it's a cinematic journey in which we're creating a feeling in you that is the feeling that she has.

When Natalie signed on for the movie, it made sense, as she has a great history of playing women under duress — she won an Oscar for Black Swan. What did she bring to this role, from that vantage point?

I think there's two movies that usually get made about a story like this. One is that there's a kind of dark comedy, the I, Tonya version, and the other is a sort of thriller about a crazy person. We weren't making either of those movies. The early conversations that I had with Natalie, I think as she understood, that it tends to be one or the other. I was telling her, "No, it's this third movie. It's the sort of magic realism astronaut movie about a woman's existential crisis."

I think she just really needed to understand how I was going to do that and how we were going to end up at the premiere and not be watching Fatal Attraction. That the movie was always her point of view and therefore a film that was championing her even as it admitted that she made mistakes, that the movie never threw Lucy under the bus.

Then you have Jon Hamm's character, he's drinking too much, he's sleeping on the job, he's almost phoning it in, but he's also at home watching and re-watching the Challenger explosion. Clearly, this guy needs some help also, but no one ever thinks to tell him he's too emotional.

The movie just, without taking a huge detour, it just acknowledges the reality of this sort of soft institutional bias in which she's told she's too emotional by someone who probably doesn't even understand what that sounds like or what that means. And Jon Hamm's character undermines her by saying, "Our girl is going through a rough patch right now." Probably he also thinks that he's helping. Do you know what I mean?

I mean, if we're going to go into space and look at life on Earth, we have to look at life on Earth, and this is a huge part of the daily reality that a lot of the human species goes through, and so without getting derailed by it, to just allow that to be part of the story. For a character who's never failed at anything to reach the age of 30, her mid-30s, and suffer this failure, to finally face a no-win situation, she can't accept it and the failure becomes catastrophic.

I wanted to ask about the Challenger scene. He's drinking heavily and rewinding to the explosion over and over again. It's wordless, beyond the TV broadcast.

I think the element of that disaster is that it was a mechanical failure and not a human error, and therefore you have no control. Those astronauts who are on that mission, they ultimately had no control over their destiny.

I think for [Hamm's character, Mark], that's the scariest thing. I think he feels like, "If it was up to me, we'd come home in one piece every time." But there's always the risk that there's a loose screw somewhere and you're going to meet your end without being able to stand up for yourself. I think it's a lot of those things.