Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Prelude to galactic catastrophe

Here's a fun thing about galaxies: Sometimes they collide.

It's hard to imagine such a colossal event, a cataclysm on a scale a million trillion kilometers across. When it happens, the gravity of each galaxy grapples with the other, distorting their shapes, drawing out tens-of-thousands-of-light-years-long streamers of gas and stars, stretching toward each others like the yearning of a lover's arms.

If the galaxies pass each other closely, especially on a fairly curved path, the streamers from one galaxy can wrap around the other, more like the tentacles of a mythical giant squid around a ship full of hapless sailors. Eventually they fall back to each other and merge, becoming one chaotically turbulent larger galaxy, which can take hundreds of millions of years to settle back down.

But to all this there is a prelude, a ramping up to the main event, a precursor of approach and catastrophic potential. It can look calm, even peaceful, but inevitability awaits.

Much as it awaits for NGC 6769 and NGC 6770, two cosmic lovers possibly on their way to embrace.

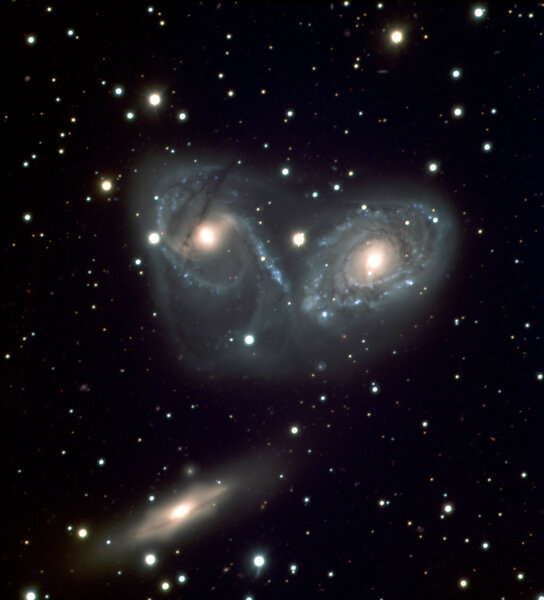

Holy. WOW.

That ridiculously spectacular photo was taken using Hubble, part of what's called a "snapshot survey": short exposures of lots of big bright colliding galaxies, meant to pave the way for much deeper images taken using future telescopes like the James Webb Space Telescope. This image was taken in a single filter (centered on orange light). So how does it have color? Astronomy image processor extraordinaire Judy Schmidt, who put together this incredible photo, used an earlier color image taken by the massive 8.2-meter Very Large Telescope in Chile as a guide, layering them in Photoshop and doing some other tricks to create what you see. So the colors you see here aren't 100% accurate or true, but should be pretty close to reality.

After recovering from picking my jaw off the floor when I first saw this image, I started looking at it more carefully. Both galaxies appear very close, as if the collision is well underway… but neither looks all that distorted. NGC 6770 does seem to be more impacted, with that straight streamer pointing toward NGC 6769 (heavily blue, meaning star formation is going on there; a usual sign of a collision), and its spiral pattern just a bit off, but NGC 6769 looks just fine. That makes me suspect strongly that perspective is playing a role here; one of these galaxies is slightly farther from us than the other, so they only look to be right next to each other. I think they're close, but not as close as the image implies.

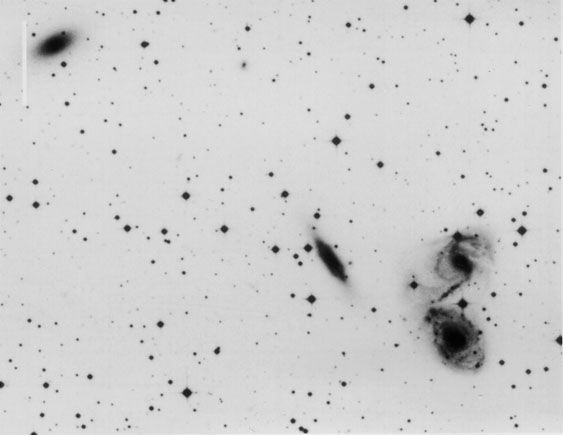

Interestingly, NGC 6770 also has that dark bifurcated streak right across it. That is clearly a trail of dust — teeny grains of silicates and carbon that pollute galaxies — in front of it, seen in silhouette. The direction is weird though; if it came from NGC 6769 I'd expect it to point at least a little bit toward it. Suspicious, I looked around for a wider-angle shot, and coincidentally found the VLT image Schmidt used to color the Hubble shot:

Ha! There's a third galaxy, NGC 6771, to the lower left, and the streamer points right at it. I wonder if it passed by NGC 6770 some time ago, a near-miss we see long after the fact. The main body of NGC 6771 is a little weird, distorted itself, which fits that scenario.

Interestingly, I looked up the distances to all three galaxies and found a mystery. We determine the distances to galaxies by their redshift, how much the wavelength of their light (which determines color) is stretched out by the Doppler shift. Both NGC 6769 and 6770 have very similar redshifts, but that of NGC 6771 is higher by a tad. If I translate that into distance, the two upper galaxies are about 175 million light years from us, but NGC 6771 is 10 million light years farther away or more!

That doesn't make sense; that's way too far in the background to have had a near encounter (for scale, these galaxies are something less than 100,000 light years across). Then I laughed to myself: We measure redshift via velocity, as if the galaxies are being swept away by the expansion of the Universe itself. But galaxies can have velocities relative to each other as they move around, what we call "peculiar velocities". If NGC 6771 got close to NGC 6770, it could have been flung away at high speed in the direction away from us. On Earth we measure its velocity as higher, but only part of that is redshift. Some part of it is true velocity as it got slingshot around! If that's correct, it got whipped around to the tune of a few hundred kilometers per second, a considerable (but not unprecedented) amount.

Think on that a moment: An entire galaxy — billion of stars, huge clouds of gas and dust — got tossed around by another galaxy, accelerated to hundreds of times faster than a rifle bullet.

Galactic collisions are terrifying in their displays of power.

Interestingly, there's a fourth galaxy (called IC 4842) lurking not too far away, and it has a similar redshift as well. It may be part of this small group too.

I didn't find too many scientific papers about this group, though one I did find confirmed my own conclusion that NGC 6770 looks more distorted than the other (note that in that paper the pair is called VV 304; there are lots of different names for the same objects in astronomy, depending on what catalog you prefer).

So it really does look like, while they've danced a bit in the past, the big event still lies ahead for these two. I don't how close they'll pass, at what speed, or what their eventual fate will be. Perhaps they're moving too quickly past each other to merge, and they'll just rip each other up a bit and move on. Perhaps they're moving more laconically, destined to physically collide and merge, as so many other galaxies have in cosmic history.

I hope that, when JWST comes online, we'll get a better idea of what the future holds for these two, some day tens or hundreds of millions of years from now. No matter what it is, though, the one thing I guarantee is that the view from here will be stunningly beautiful.

My thanks to Judy Schmidt for tweeting about this gorgeous image and talking to me about her process of creating it.