Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

The nearby supernova no one saw

Sometime between early 1995 and 1996, a supernova went off in a very nearby galaxy. The weird thing is, nobody noticed.

That's… bizarre. How do you miss an entire exploding star?

Yet everyone did. It went completely unrecorded, not discovered until years later. The reasons no one saw it at the time may simply be that it was a faint explosion as such things go, and it happened in a part of the sky where there's so much stuff going on that it was hard to spot.

The story starts in a galaxy technically named ESO 97-G13, but everyone just calls it the Circinus Galaxy, due to the constellation we see it in. It's one of the closest galaxies to us, just 12 million light years away. That's only about 5 times as far as the Andromeda Galaxy, one of the brightest in the sky, so you'd expect it to be big and bright in the sky as well. However, it's unfortunately located so close to the plane of the Milky Way (only 4° off) that it's heavily blocked by the gas and dust in our own galaxy. That makes it much fainter and more difficult to observe.

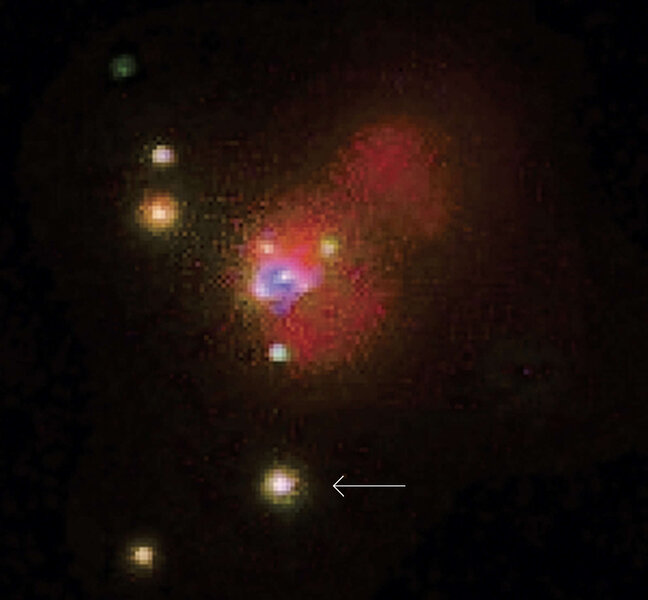

The galaxy is pretty remarkable; it's an active galaxy, meaning the supermassive black hole in its core is actively eating matter, and that stuff forms a disk around the black hole, gets super hot due essentially to friction, and glows very brightly. You can actually see material being blasted away from the galaxy from all that energy generated in the core.

Astronomers like to study nearby galaxies because they have lots of fun things in them we can see better due to proximity, so a team of them used the Chandra X-ray Observatory to look at it, to see what sorts of things they could find. They mapped the galaxy out in 2000, and found two exceptionally bright high-energy sources. One turned out to be a smaller black hole gobbling down matter and blasting out X-rays, but the other source was harder to understand. It looked like a young supernova but they couldn't be sure.

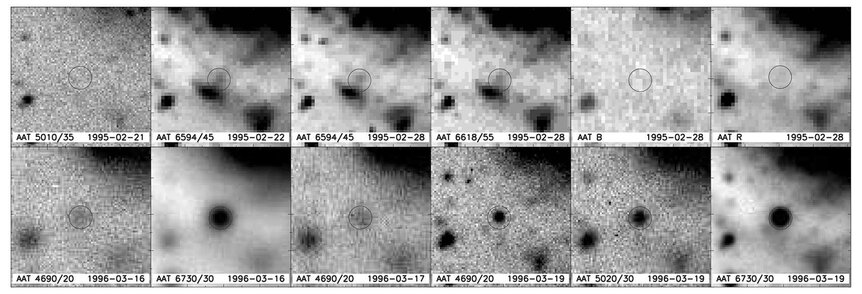

It wasn't until 8 years later that another team of astronomers combed through archived data from many different telescopes and were able to confirm that this was indeed a supernova, the explosion of a massive star at the end of its life (what we call a core collapse or Type II supernova). Although the observations they looked over spanned quite a bit of time, the best they could do was say that the star exploded sometime between 28 February 1995 and 16 March 1996. After that later date the supernova is definitely seen, but before then the data are ambiguous. The explosion was dubbed SN1996cr.

Judging from the observations in various wavelengths (radio, optical, X-rays) they were able to put together a decent picture of what happened. It was a massive star, still inside the star-forming nebula from which it was born. Shortly before the star exploded, probably only a hundred years or so (!), it started blowing out a very dense wind of gas. This carved a huge cavity in the gas around it, nearly a tenth of a light year in radius. The wind plowed up a lot of material, more than half the mass of the Sun.

Then the core collapsed, and the star exploded. The debris screamed away at high velocity, basically coasting through the empty region in the cavity until it reached the bubble's edge a year or two later. The high-speed collision created a huge burst of energy in radio waves and X-rays, lighting up the material around it. This is clearly seen in the data.

But what about the explosion itself? A lot of the light we see in a supernova is due to the blast wave from the core collapse chewing its way out of the upper layers of the star, and then that material glowing as it gets blasted away. But this star blew off a considerable amount of its upper parts before exploding, so there wasn't as bright a flash. Overall, the supernova was fairly underluminous… a big reason no one saw it when it happened.

Since it occurred in a star-forming nebula that had lots of dust in it, that dimmed it further. It being so close to the plane of our galaxy reduced it even more. It never got brighter than about 16th magnitude — the faintest star you can see by eye is 10,000 times brighter! So, in retrospect, it's no surprise no one noticed. The odds were really stacked against it.

Still, this was one of the closest supernovae in the past hundred years or so. SN1987A happened in a satellite galaxy to the Milky Way, and SN1885A (yes, 1885!) was in the Andromeda Galaxy. On average they go off once or so per century per galaxy, so nearby ones are relatively rare.

The last one visible to humans in our own galaxy was in 1604, and the last one we know of, G1.9+0.3, went off probably less than 150 years ago near the galactic center, and like SN1996cr was heavily obscured by dust, so it wasn't discovered until 1984.

That really makes me wonder yet again when the next one will blow, and what it will be. There are lots of candidates we can see, and far more we don't even know about. It's a big galaxy with a lot of obscuring junk in it. Betelgeuse, Antares, Rigel, Deneb… all these don't have long left, but that's in astronomical terms. A hundred thousand years, for Betelgeuse, for example… But we'll have hundreds, maybe thousands, of supernovae in our galaxy before Betelgeuse goes.

Chances are you've never heard of the next star to go. But when it does, oh, trust me: You'll hear about it.