Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

There's a big black spot on the Sun today… and scientists predicted it

A new and respectably large sunspot has rotated into view on the face of the Sun, which would be interesting in any case since the Sun has been very quiet for years. But what makes this even more remarkable is that solar scientists predicted this would happen, even when this spot was on the other side of the Sun!

Sunspots are regions on the Sun's surface of intense magnetic strength. Normally, huge parcels of ionized gas (called plasma) inside the Sun rise through the interior due to their heat, and when they reach the surface they cool and fall back down. This is pretty much what happens when you heat a pot of soup, too (thought it's a liquid and not plasma).

But if the magnetic field embedded in that plasma gets tangled up when it reaches the surface, the parcel cools but can't sink back down. It persists, and since it's cooler than the surrounding material it appears dark: a sunspot.

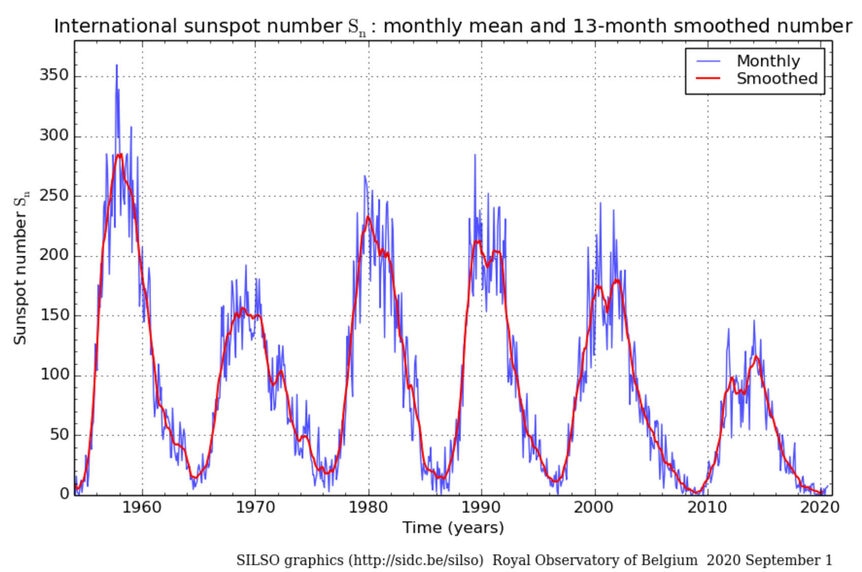

Also, the Sun goes through cycles of magnetic activity, which manifests in one way as increasing and decreasing numbers of sunspots over time. It goes from minimum to maximum and back to a min over about 11 years. Cycle 24, the last one, ended last year, and Cycle 25 started up in September 2019.

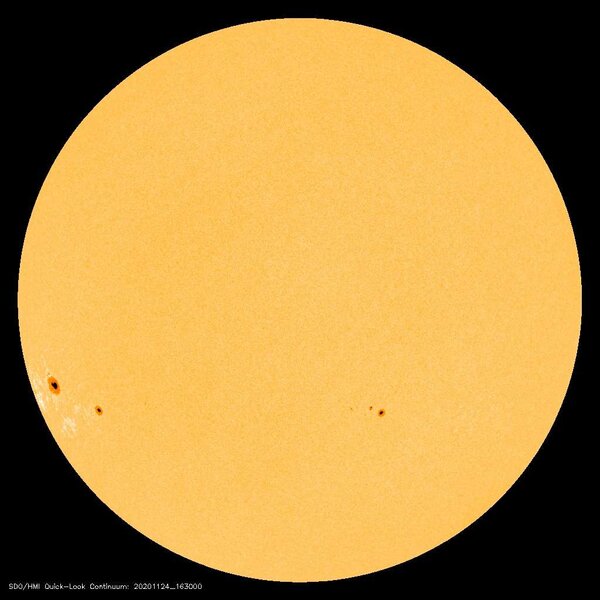

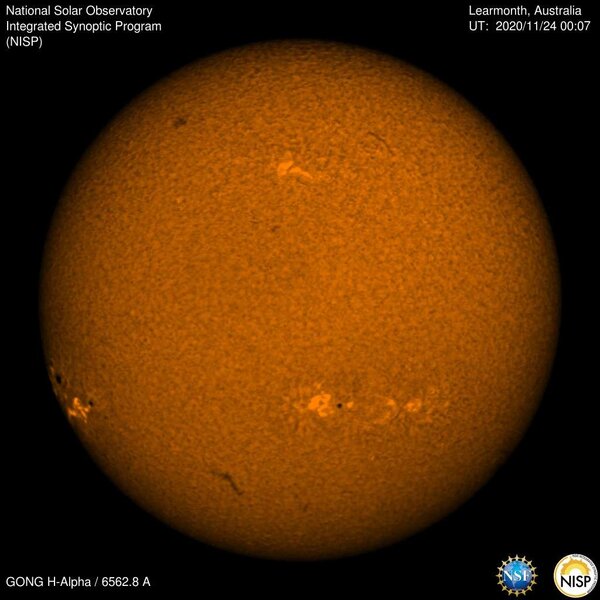

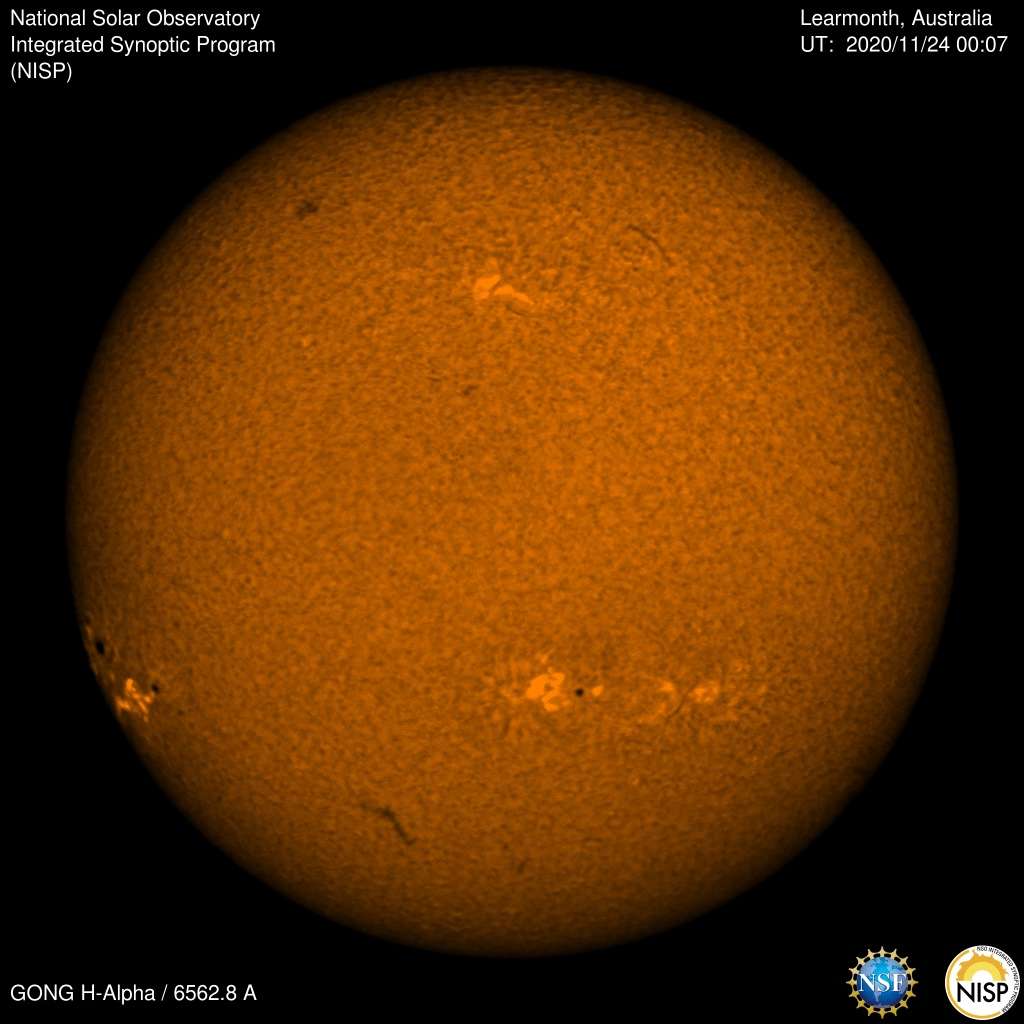

A few spots have been popping up on the Sun, but on November 23 a new one peeked over the Sun's western edge, rotating into view. It was already decent-sized, meaning it formed while on the far side of the Sun, which we cannot see from Earth.

But that doesn't mean scientists have no idea what's going on over there. In fact, they're getting pretty good at predicting what's happening on the Sun's far side. They knew this spot was there long before we could actually see it.

That's because of a field called helioseismology. On Earth, seismic waves are sound waves (more technically acoustic waves) that travel through the Earth. By measuring them we can figure out what the deep interior of the Earth is like (which is how we know there are layers like the core and mantle down there).

The same with the Sun. All the furious activity on the Sun's surface and deep inside it create acoustic waves that travel around. As they do, the Sun's surface vibrates like a drum. By very carefully measuring those vibrations, scientists can tell now only what's going on inside the Sun, but also on its other side.

The magnetic fields permeating the Sun interfere with these waves, and so they too can affect what's seen. That's how the scientists knew this spot — called Active Region 12786 — was coming around. The signal for it first appeared on 14 November, but it was weak and wasn't big enough to base any claims on. But it grew quickly, and in just one day was big enough to count as a solid detection.

And sure enough, on 23 November it became visible as the Sun's roughly month-long rotation slowly brought it into view from Earth.

The spot itself is about 40–50,000 kilometers across. That's easily three times wider than Earth! If you tossed the Earth into the spot it wouldn't even touch the sides.

To be clear, this kind of prediction has been done many times before; just a couple of weeks go they predicted Active Region 12781, which was visible on the Sun after it rotated into view as well. What makes this new one cool is that the Sun is so quiet the signal from 12786 was very clear, and that it's a big spot. We usually don't see ones this big until well into new cycle. I wouldn't read too much into that for now; the Sun is mercurial* and it can be hard to know what it's up to in any given cycle.

But this sort of thing is important to know. Magnetic fields on the Sun can get pretty feisty, and they store a vast amount of energy. That can be released in huge explosions called solar flares, and even bigger ones called coronal mas ejections. Both of these can do real damage to satellites in orbit around the Earth, and cause widespread blackouts on Earth's surface (they can create vast flows of electricity under the surface, called geomagnetically induced currents, which put a lot of stress on generators and power distribution).

As it happens I saw the spots from AR 12781 a week or so ago, and another group (AR 12783) just the other day; I have a pair of solar binoculars specifically designed to look at the Sun. DO NOT ever look at the Sun without proper aid, especially using things like binoculars or telescopes unless you know what you're doing. And even then you have to be very very careful, unless frying your retinae and boiling the vitreous humor in your eyes are desired outcomes.

Instead, you can look at the current Sun observations from NASA's SOHO online, including the visible light image. Another good site is Solar Monitor, as well as current images from the Solar Dynamics Observatory.

And remember: The Sun may seem familiar and friendly, but it's actually a ball of nuclear-fueled boiling plasma well over a million kilometers across, and its magnetic field can literally connect with ours even from over 150 million kilometers away. We rely on it for warmth and light, but we very much need to keep an eye on it in case it decides to throw a little more our way.

*Haha! Ha!