Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

30 years later, we can create false memories, Total Recall-style

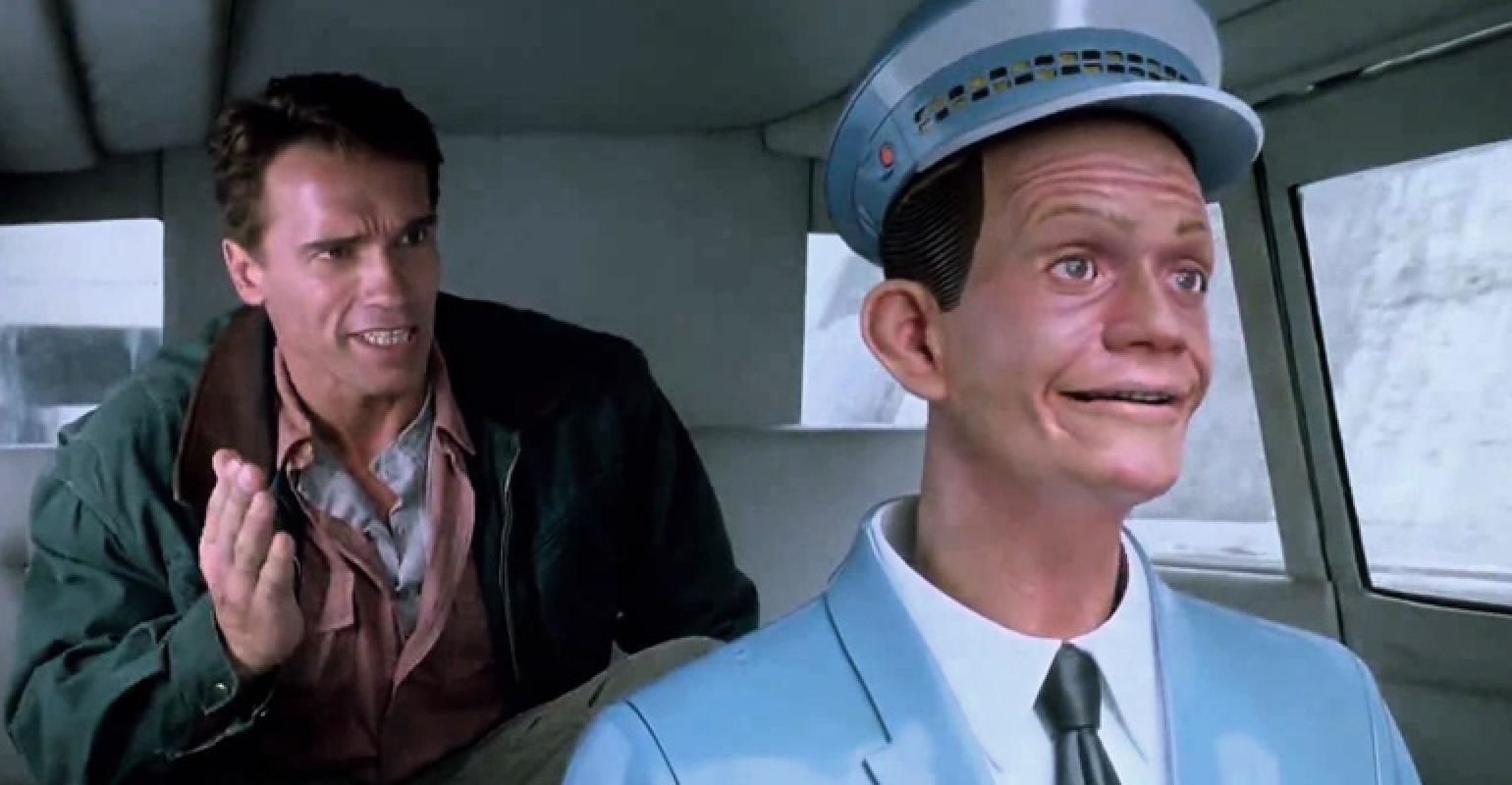

This year marks the 30th anniversary of Total Recall, the 1990 sci-fi action film that introduced the world to removable heads, digital gaslighting, and getting your a** to Mars.

The film is set in 2084, where Douglas Quaid (Arnold Schwarzenegger) needs a little excitement in his life. With an actual trip to the red planet beyond his grasp, Quaid takes a trip to Rekall, a company that offers to implant memories for enjoyment. It’s the ultimate daydream. You may not be able to travel the stars, but if you think you did, what’s the difference?

But there's a horrible catch — once you’ve entered into a fictional mental state, how can you ever know you’ve come out of it? Once you’ve willingly altered your mind, how can you ever trust your own thoughts or experiences again? It’s a cautionary tale, warning viewers against the temptation of altering one’s mind.

But when did a cautionary tale every stop anyone from doing anything? So it got us thinking: Is it actually possible to implant false memories?

THE ANALOGUE METHOD

The primary conflict in Total Recall is Quaid’s inability to parse reality from fiction. He has no way of knowing if anything he’s experienced has actually happened to him. And that prospect is rightfully frightening. But all of us experience that very same thing, to varying degrees, every single day of our lives.

Research on memory suggests that our remembrances of past events are just about half wrong. It’s the sort of knowledge that rankles the nerves, the sort of thing we don’t want to accept. How can 50 percent of what you think you know about the world and yourself be, well, wrong?

You can learn a bit more about how your own memories are lies in this wacky video:

In order to understand what’s causing our memories, even emotionally significant memories, to degrade to such an extent, we first have to understand how memories are formed.

Most of what happens in your day-to-day life isn’t stored in long-term memory. You might have a moment here or there that's held onto, but for the most part, the nooks and crannies of your life fall by the wayside. When something significant occurs, that information is stored, becoming a memory engram. But it doesn’t happen right away. There is a period known as consolidation, in which the brain is taking all of the relevant information and wrapping it up in a nice little bow for you to hold onto. When that process is finished, you have a memory.

While we often think of memories as being hard-coded in our minds, that doesn’t seem to be the case. To use the brain-computer analogy, we like to think of memories as files saved on our hard drives, ready and waiting, in perpetual perfection, for us to open and peruse at our leisure.

Instead, it’s more like a file which, every time we access, we need to save again, as if for the first time. And anyone who has ever seen a repost of an older meme knows the quality of the image degrades over time. This is sort of what’s happening in our minds.

The research suggests that whenever we access a memory, a new period of consolidation occurs, and during that time the memory is vulnerable to alteration.

Our most treasured memories are like vintage comic books or antique toys. You can take them out of their protective casings to play, but if you do, the pages will yellow and the binding will weaken. The shiny bits of paint will scuff. In short, each time you think back on the past, there is a cost. And that’s when we’re not trying to alter our recollections.

As outlined in this Scientific American article, it’s relatively easy to implant false memories in otherwise unsuspecting people, with at least moderate success. It’s why interrogators and therapists aren’t meant to ask leading questions. A person can pretty easily be led down a road that ends at them believing and remembering something that never happened at all. Sometimes this is referred to as "gaslighting," after the 1944 film Gaslight, wherein a woman’s husband manipulates her into questioning her own view of herself and the world.

Memories are malleable, and, for better or worse, we’re pretty good at messing with them, either intentionally or otherwise, even without the use of technology. Which brings us to …

CHEMICALS, LASERS, AND TINY BRAINS

Steve Ramirez and Xu Liu, researchers at MIT, figured out a way to implant false memories into the brains of mice. They accomplished this by the use of optogenetics, a process involving glowing chemicals, filaments implanted in the brain, and lasers to identify and later excite specific memory engrams.

They started with a mouse in a box. This first box was safe and the mouse was allowed to explore unhindered. Then they used a second box that differed in sight and scent and delivered an electric shock. Using glowing chemicals to identify the engrams associated with the fear response, they were able to place the mouse back in the first box, where no fear response was associated, and activate the memory.

The result: a mouse with a false memory of being shocked in the safe box. While this research has incredible implications for our understanding of memory, and many potential positive applications for dealing with things like PTSD or degenerative neurological disorders, it’s a little bit frightening (especially for the mouse).

It’s not too difficult to see how this sort of procedure, taken to its endpoint, could result in the malicious manipulation of memory in humans.

This same process was used by Todd Roberts and team at the UT Southwestern Medical Center in Texas, this time on birds, and to less nefarious results. They used optogenetics to implant memories in developing songbirds, but instead of implanting a memory of fear, they used laser pulses to implant memories of musical notes. The hypothesis was that juvenile songbirds learn how to sing from their parents by listening to the sounds they make, in much the same way human children learn to speak. And it worked.

Soon the birds in the study began singing a song they never actually heard, except inside their own minds.

To be sure, the memories we retain are comparatively more complex than a fear response, or notes of a song, and altering them will likely be comparably complex. Still, researchers are optimistic that this line of inquiry will one day lead to a better understanding of how we learn, how we store memories — both positive and negative — and why we forget.

Someday, in the relatively near future, we might be able to intervene on behalf of those with learning disabilities, remove or soften traumatic memories, and prevent memory loss.

But it will probably be a while before you can find yourself embroiled in a tale of espionage and mortal peril on the way to Mars. For that, we should all be grateful.