Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Cool: The galaxy's oldest globular cluster has been found. Cooler: Our galaxy is eating it.

Extremely ancient star cluster torn apart by the Milky Way.

One of my very favorite kinds of cosmic objects are globular clusters: Roughly spherical collections of hundreds of thousands, and sometimes millions of stars, all held together by their mutual gravity.

They tend to be pretty compact, just a few dozen light years wide, so the stars are incredibly crowded, making them look like glittering bees swarming around a hive. They're beautiful.

They're also old, most having formed along with their parent galaxies 12 or so billion years ago. We know this because the stars in them tend to have very low abundances of heavy elements like iron. These elements are made when massive stars end their lives as supernovae, exploding and blasting them out into space, where they are incorporated into the next generation of stars. As time goes on, the new generations of massive stars make more of these heavy elements, so younger stars are born with higher amounts already in them.

By measuring the abundance of these heavy elements (what astronomers call metals) we can gauge the age of stars in general, and globular clusters specificially.

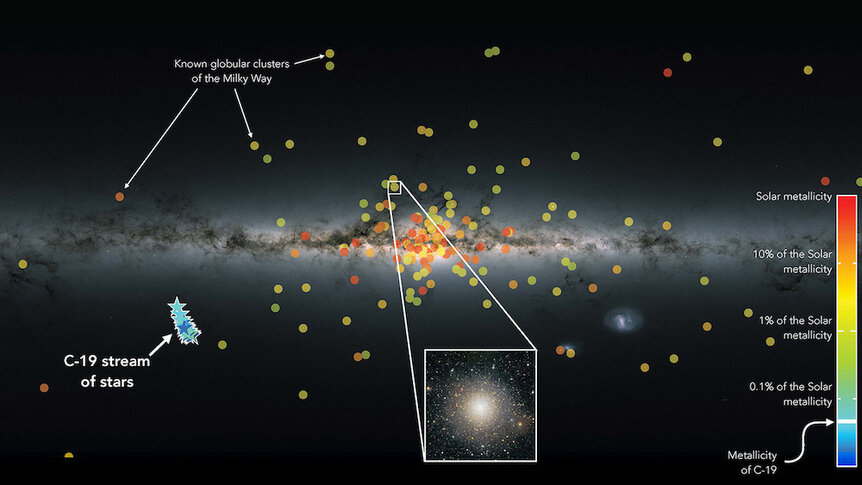

And that's what makes a new discovery very exciting (link to paper): Astronomers have found a globular cluster with the lowest abundance of heavy elements ever seen. Most globulars have a floor of heavy metal abundance, a level below which few at best are seen, and this is about 0.2% the amount of iron seen in the Sun. The new cluster has a level of less than 0.05%, far far lower. This metal-poor cluster must be extremely old.

But there's more! It's not a cluster any more: Repeated passes through our galaxy have torn the globular apart, so it's not so much a cluster of stars anymore as it is a stellar stream, a long, thin noodle of stars all following the original cluster's galactic orbit.

The stream is called C-19, and was not found using astronomical images. Instead, it was found in data taken by Gaia, a European Space Agency observatory that measures the positions, motions, colors, and distances of well over a billion stars in the Milky Way. The database of these measurements is huge, of course, but it can be mined to look for stars that, for example, are all in the same part of the sky, roughly the same distance from Earth, and share a common velocity through space.

A cluster fits that bill, but so do stellar streams. Dozens of these have been found, and they are remnants of globular clusters (and some dwarf galaxies) that have passed through the Milky Way, and our much bigger galaxy's gravity has pulled the objects apart. Over time some stars are given an extra kick in velocity from our gravity so they pull ahead of the cluster, while others are slowed, and they lag behind. Over millions and even billions of years this stretches the cluster into a stream, which can be found in the Gaia data.

C-19 is just such a stream. The stars in it are roughly 60,000 light years from the Earth, halfway across the Milky Way from us, yet the stream is an incredible 15° long (30 times the size of the full Moon on the sky) at least, equivalent to a physical length of 15,000 light years! That's over 10% the diameter of the galaxy itself, so this cluster has really been stretched out. The stars' elliptical orbits take them as close as about 25,000 light years from the galactic center (roughly the distance of the Sun from that point, coincidentally) and as far out as 90,000 light years.

The low metallicity of the stars in the stream were found by the Pristine survey, which used the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope in Hawaii to take spectra of stars (breaking their light up into individual colors, which can yield elemental abundances) and find extremely low-metal and therefore very old stars. Some fainter stars were observed with other telescopes as well to confirm the findings.

C-19 likely has thousands of stars in it, with a total mass of about 8,000 times that of the Sun (most stars are lower mass than the Sun; if each star had the Sun's mass there'd be 8,000 of them, but since most are lower there are significantly more than that).

The abundance of iron in the stars is extremely low, about 0.04% that of the Sun, implying vast age. The cluster may have been born 13 billion years ago, making it ancient indeed. The Universe itself isn't much older than that.

What makes this so astonishing is that it was thought that the floor of low abundance was higher than this, and that massive globular clusters might not be able to form early enough in the Universe to have such low metallicity. The very existence of C-19 shows this is not true, and that at least one clearly did.

And if there's one, there's more. It's possible that over the eons most of these have been totally disrupted by the Milky Way, completely torn apart, their original stars incorporated into the galaxy's population so thoroughly they're completely dispersed. C-19 shows that it's possible that some can still be found. Not intact, but existing as streams, betraying their presence by the similar motions of the stars. These are difficult to find, but obviously not impossible.

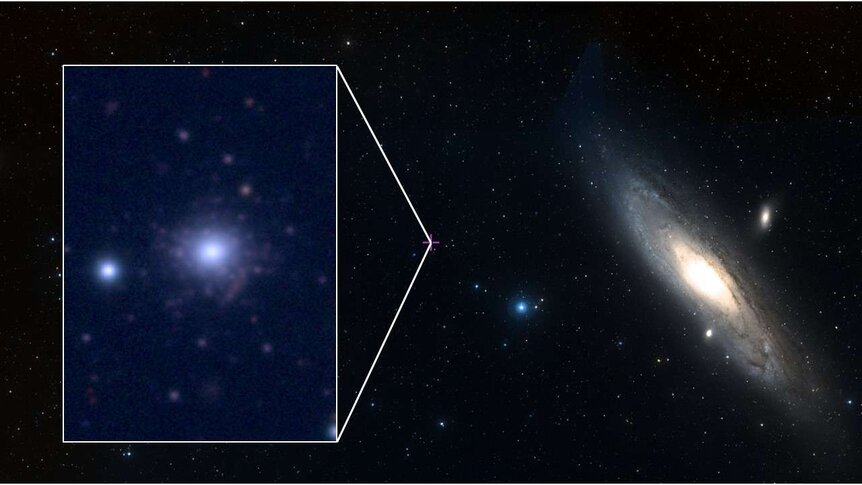

I'll note that our sister galaxy, the Andromeda Galaxy, has its own cohort of globular clusters, and one, called RCB EXT8, is also incredibly low-metallicity and therefore also very old. Its metal content is about 0.1% of the Sun's, which is very low but still higher than C-19's. On the other hand RCB EXT8 is still intact, still a cluster, making it easier to see over the 2.5 million light year gulf between us and Andromeda.

Finding C-19 is exciting because we don't know very much about our galaxy's very distant past. Extremely old stars are difficult to find, typically faint and far away, and generally found one by one. This stream means thousands can be seen, all with similar characteristics, and that can be studied to learn much about the Milky Way's early days, as well as learn how globular clusters formed and changed over time. And its existence implies there could be more like it out there, just waiting to be discovered.

This is like cracking the door open to cosmic history, and C-19 is giving us a peek on the other side.