Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Castle Greyhawk, the lost dungeon that kicked off Dungeons & Dragons, still inspires players today

In the early 1970s, when Dungeons & Dragons was in its nascency, still floating around in the heads and in the scribbled notes of inventors Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson, it needed a locus, a testbed, somewhere in which the very first roleplayers could descend to fight monsters, seek treasure, and die in the dark. In other words, it needed a dungeon.

For the group of family and friends who gathered regularly at Gygax’s Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, house to play “The Fantasy Game,” as it was then known, that dungeon was Castle Greyhawk. It was a far cry from the modules they would soon begin publishing under the company name Tactical Studies Rules, or TSR. Those were locales and adventures that could be packaged up and sold, but Castle Greyhawk was on an entirely different scale. By the time Gygax and his 17-year-old co-dungeon master, Rob Kuntz, had finished tinkering with it, this ur-dungeon was a staggering 50 levels deep.

Back then, there was no Player’s Handbook, no Monster Manual: Every magic item and each monster was a new unknown. Kuntz, now approaching his 65th birthday, remembers the electrifying newness that helped the DM “summon fear” for the players. “These people were rigid with expectations, they would hang on our every word. Sometimes,” he tells SYFY WIRE, with evident satisfaction, “they would run just from the descriptions alone.”

Early D&D fans were enthralled by Castle Greyhawk and what went on behind its walls. They lapped up the stories of exploration and derring-do that Gygax would publish in magazines and newsletters. According to Allan Grohe, a Greyhawk devotee, the castle was, for a while, “the face of D&D.” It represented all that the game could be.

But for a long time stories of the dungeon were all that fans had. While the setting that gave it its name, the World of Greyhawk, was the basis for many of TSR’s modules, Castle Greyhawk, Gygax’s magnum opus, never actually saw the light of day. It was never released. Instead, as Allan puts it, the castle “loomed large in the imagination of the fanbase.”

Indeed, for a particular breed of roleplaying enthusiast, Castle Greyhawk represents the Holy Grail. Bill Meinhardt is among their number. Meinhardt is the owner of the largest fantasy RPG collection in the world, and his shelves are packed with more than 13,000 artifacts. For 40 years, Meinhardt has made it his mission to collect and preserve a copy of every RPG product ever published. Castle Greyhawk is no exception to this Beholder-like quest.

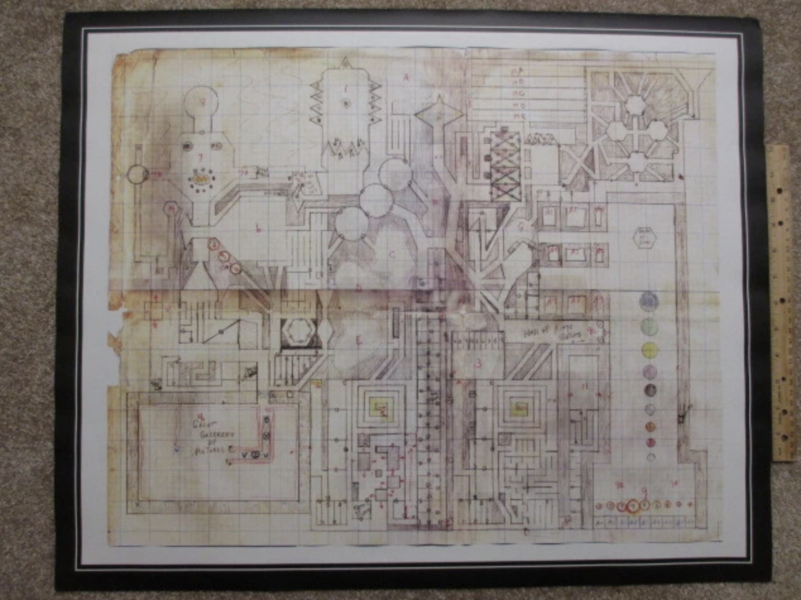

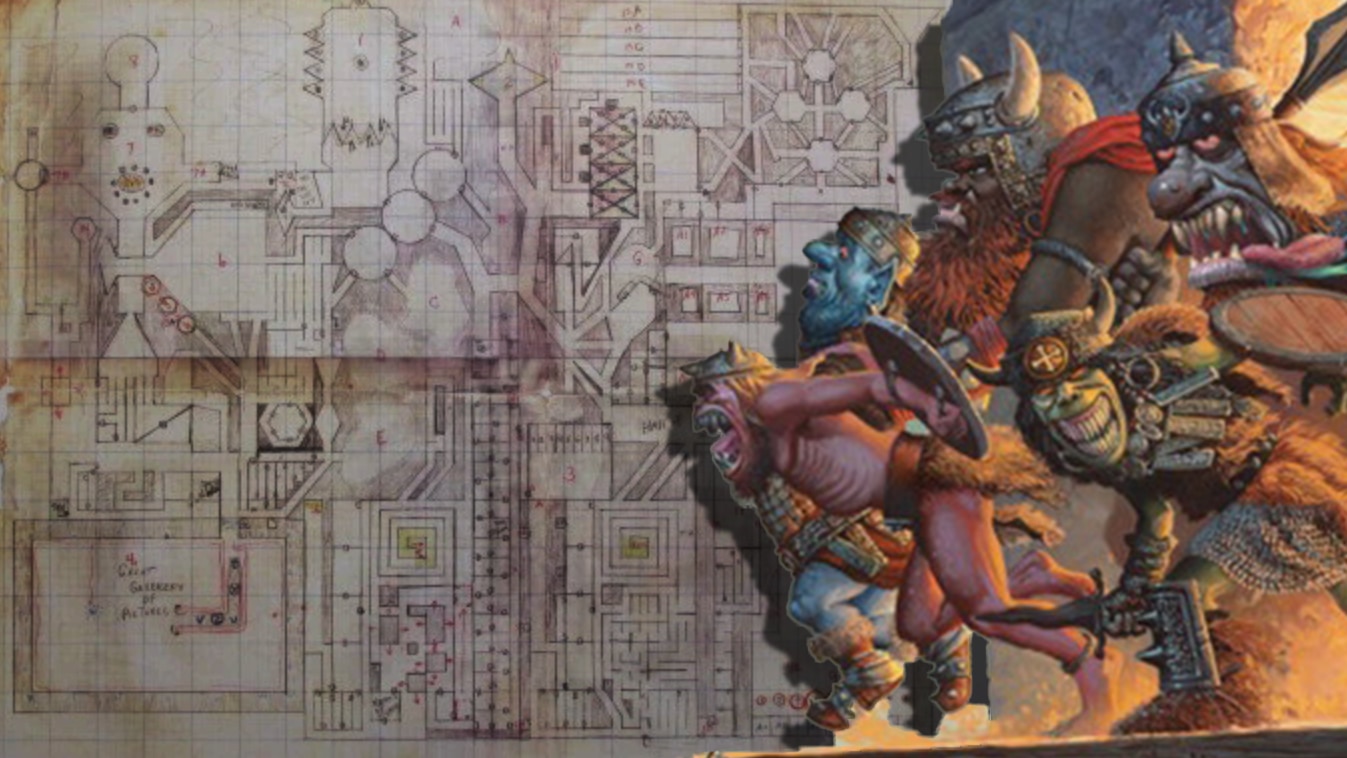

With the mindset of a museum curator, Meinhardt places particular value on the history of the hobby. He shows SYFY WIRE a prized relic, the original map of a Rob Kuntz Greyhawk level: a city magically shrunk to fit inside a bottle. “Greyhawk was first to me, it was right at the top of the list,” Meinhardt says. “It’s where they started playing, so the fact that I’ve been able to pick up some Greyhawkian artifacts has been a true joy.”

Releasing Castle Greyhawk in playable form would have been a formidable task, and not just because of the dungeon’s size. Gygax and Kuntz were known for making up new details as they played and did not keep comprehensive notes. Their maps were lightly outlined, to allow for flexibility and improvisation, and features invented on the fly were merely jotted down in brief.

The pair nonetheless made several attempts to piece together their notes and memories into a finished product. But the saga of Castle Greyhawk’s attempted publication is one dotted with disaster, from Gygax’s ousting from TSR in 1986 to the folding of his subsequent company, New Infinities Productions, in 1989. A final effort, which Gygax worked on amid worsening health until his death in 2008, resulted in a few sizable levels of a renamed Castle Zagyg: an incomplete work, but as Meinhardt puts it, “probably as close as we are going to get” to a published Castle Greyhawk.

SYFY WIRE reached out to the current owners of D&D, Wizards of the Coast, for comment on Castle Greyhawk, but they declined to comment.

So, for a fan like Grohe, who has dedicated decades to studying the castle, it’s necessary to look beyond what has been released and see what can be gleaned from other sources. “There have been far fewer formal, polished products published about Castle Greyhawk than there have been manuscripts, fragments,” he explains.

Early on in his involvement with D&D, Grohe decided he would create his own copy of Castle Greyhawk. His first instinct was to approach this project as a historian, but that outlook has evolved over the years. “When I was first capturing all of this, I wanted to understand what Castle Greyhawk was,” he says, “the shape and structure of the castle, the number of levels ...” The trouble was, “there wasn’t anything to work from back in the ‘80s.” Grohe had to play detective to build up a picture of the castle from obscure stories and snippets, and where details were missing, he “had to make it up.”

Some would find the lack of readily available information frustrating, but for Grohe, that was half the fun. Nowadays, there are forums and chatrooms devoted to the castle, and Kuntz has periodically been in dialogue with the fanbase (as was Gygax prior to his death in 2008), but in the pre-internet age, uncovering new details took real digging. “Part of the mystique of the setting is that you kind of had to work to get access,” Grohe says. “The piecemeal nature of it and that random reinforcement of discovering little bits of lore in this book and that book definitely builds my interest.”

Over time, Grohe has personalized Greyhawk, picking and choosing his own version of the castle, incorporating or discarding new information as he discovers it. “I realized that, as bits and pieces of the castle were being published, it wouldn’t jive with what I had, but I was okay with it by that point.”

Nowadays, Rob Kuntz has mixed feelings about Castle Greyhawk. He is convinced the dungeon is “wrapped up in some kind of curse,” which has made releasing it a nightmare. “I’ve always tried to get it done in a positive thrust, and something has always stepped in the way.”

Kuntz says that focusing on the fine details of Castle Greyhawk is the wrong approach. For one thing, the dungeon never stayed the same for long. “A lot of it was no man’s land down there, it was still being fought over," he explains. "Certain sections would be taken over by some power, and we’d change it.” And there can be no Castle Greyhawk “canon,” because the location changed depending on the actions of the players. “In a sense, it was a real environment, not a static thing.”

For Kuntz, the specifics of Castle Greyhawk are less important than the spirit of it. He feels that, today, fans should take what they can from the castle but then move forward to craft their own “living environments.” His advice is: “Don’t keep looking at the past, but if you do, look at the qualities, not the name. Because Greyhawk is an ongoing idea, just like the game was. So latch onto the concept ... All you have to do is create your own.”

It appears that one group of hobbyists is doing just that. In recent years, old-school roleplaying has exploded in popularity. New generations are increasingly taking an interest in a retro style of D&D, rediscovering and redesigning older variants of the game for themselves.

And many of these “old school” designers have produced their own immense dungeons, their own Castle Greyhawks: passion projects, enormous environments full of factions, NPCs, traps, and wonders, each one large enough to keep a party busy for years. A new term has arisen for this (old) new playstyle: the mega-dungeon campaign, where, rather than adventuring across the land, the players delve ever deeper into a single location.

Each mega-dungeon maker puts their own spin on the formula, resulting in a massive amount of variety. There’s Stonehell, an ancient prison filled with the monstrous remnants of its former inmates. Or Maze of the Blue Medusa, a dungeon inside a painting, brimming with art, tragedy, and philosophers. Or Highfell, an ancient wizard school that can fly.

Mega-dungeon designer and RPG blogger Patrick Wetmore chose to “embrace the ridiculous” when devising his own take on the genre. His post-apocalyptic dungeon, the enormous “Anomalous Subsurface Environment,” features mad magicians, rabid clowns, and an underground version of Miami. Wetmore believes that, in the hobby’s early years, a lack of published examples discouraged players from attempting mega-dungeons that could rival Greyhawk. “TSR was always shipping relatively small dungeons that could be completed in a short amount of time, and that became the model that dungeon masters followed,” he explains.

Grohe agrees with this conclusion. He says that, until recently, “people weren’t publishing giant dungeons.” But that has changed with the old-school revival. Now, Grohe says, “the mega-dungeon is alive and well and thriving in ways that it never really did in the 1980s.”

Castle Greyhawk may have been the first D&D dungeon, but in its day it was an outlier, more of a curiosity than something fans would try to emulate. Today it’s the source of inspiration for a growing mega-dungeon genre and championed by hundreds of new roleplayers looking to get back to the roots of the game.

So while Castle Greyhawk seems doomed never to be published, its legacy is safeguarded, not just by fans seeking to preserve the game’s history but also those producing creations of their own.