Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

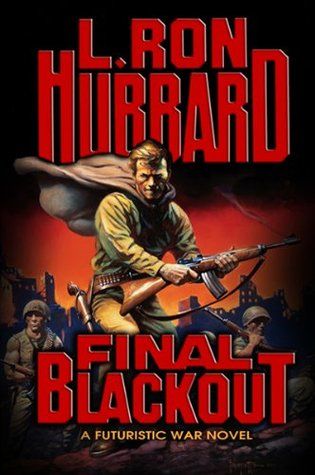

Final Blackout: How do you read an L. Ron Hubbard novel and not think of Scientology?

In 1938, the science fiction writer and editor John W. Campbell was paired up with a pulp writer called L. Ron Hubbard. Better known for being a highly prolific writer of pulp fiction, Hubbard reportedly didn't have all that much interest in sci-fi until Campbell took him under his wing and published many of his more notable short stories. Writing for Campbell's magazines Unknown and Astounding Science Fiction, Hubbard reportedly churned out over 100,000 words a month at his peak. Eventually, Hubbard would take a different route in life away from science fiction, instead choosing a life of antics have become the stuff of infamy to the general public. But before Dianetics and Thetans and Tom Cruise, there was merely the guy who wrote lots of space stories and the editor who heartily encouraged him. From that collaborative partnership came Final Blackout.

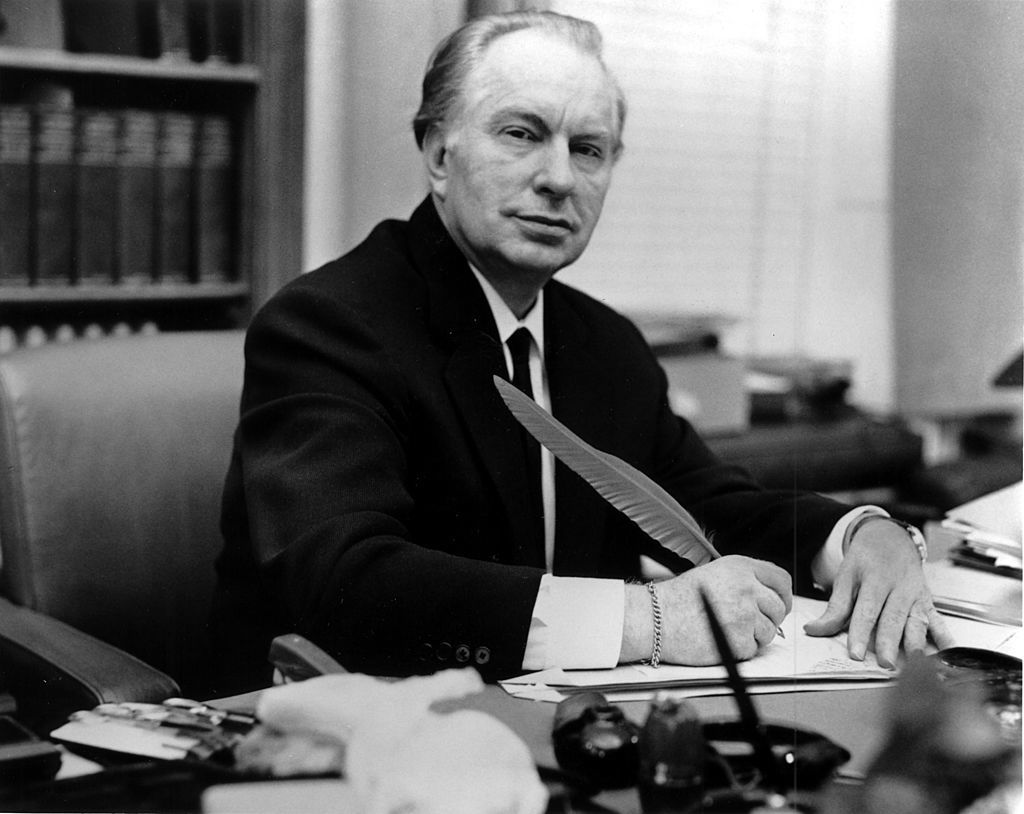

Reading L. Ron Hubbard’s work now is an odd experience and one that’s nearly impossible to do without being smothered by decades of historical, cultural and socio-political context. His record as an author of fiction has become impossible to separate from his work as the creator of Scientology, in part because the Church of Scientology has made it so. An L. Ron Hubbard book is never just an L. Ron Hubbard book. The copy of the Hubbard book I purchased for my Kindle was published by Galaxy Press, the company set up to exclusively publish Hubbard's fiction, and one whose profits, according to Forbes, go in part to Applied Scholastics, a "nonprofit organization that promotes Hubbard's ideas regarding education." Said charity is sponsored by the Church of Scientology and has faced numerous criticisms over the years about its practices.

Reading anything by Hubbard and being able to not think about Scientology is a skill unto itself. Final Blackout was published in 1948, two years before the publication of Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health. At the time, Dianetics was a best-seller, an alluring bastardizing of psychoanalysis that proved appealing to many Americans looking for answers after the hell of the Second World War (Hubbard also served and his military record during this time has been heavily disputed). The book is now a canonical text of Scientology, the practices and ideas of which have been extensively refuted.

The big title in Hubbard’s canon of fiction is, of course, Battlefield Earth. Written four years before his death, the 1000+ page novel was his first science fiction-title since the heyday of his pulp career and was hyped up as his return to the genre. Nowadays, the book is more a punchline than anything else, mostly because of the truly hilarious John Travolta movie, but despite having some fans (including Mitt Romney of all people), the reviews were mostly tepid. The book's status as a best-seller is also questioned after stories emerged of the Church of Scientology organizing mass book-buying campaigns to ensure the title remained in the New York Times Best Seller List. Whether or not you buy Hubbard’s own insistence that Battlefield Earth doesn’t have anything to do with Scientology — and given that Hubbard himself informed his followers that the book was inspired in part by his "disgust[ed] with the way the psychologists and brain surgeons mess people up," that seems hard to believe — separating art from artist is harder than ever when there’s a multi-billion dollar organization with religious tax-exempt status ensuring those ties stay tightly bound together.

All of this made choosing an L. Ron Hubbard book to read for the very first time an intriguing and oddly exhausting process. How do you even begin to read one of his countless titles without getting bogged down in decades of Scientology discourse? Can you ever do that? Does the Church of Scientology even want you to be able to do that? Ultimately, I settled on Final Blackout for three reasons: One, it has genuine critical acclaim; two, it was supposed to be made into a movie; and three, it’s short. Sorry Battlefield Earth, but I wasn’t sticking around for 1000+ pages.

First published in serialized form in Astounding Science Fiction in 1940, a year after World War II started but before Pearl Harbor, Final Blackout imagines a future world decimated by a nuclear apocalypse years before the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The planet’s population has been dramatically reduced through a series of wars and a form of biological warfare known as soldier's sickness has left England under quarantine, ruled by the Communist Party. The protagonist of the novel is an unnamed Lieutenant, an officer of the British Army. He leads a small army of only 168 men, soldiers gathered from the various Allied nations, across the ravaged continent in search of food and supplies. When the battalion is recalled back to General Headquarters (G.H.Q.) by their commanding officer, General Victor, they discover that the General plans to strip the Lieutenant of his powers and break up his troops. Fearing for the future of their troops and the country, the Lieutenant leads a battle to overthrow the Commies and instill himself as leader.Final Blackout has its fair share of fans. A name no more prestigious than Robert A. Heinlein, author of Stranger in a Strange Land and Starship Troopers, told John W. Campbell, "If you write to L. Ron Hubbard, please tell him for me that I consider his Final Blackout one of the most nearly perfect examples of literary art it has been my privilege to read. His comprehension and ability to portray the character of the commissioned professional military man is startling. I find myself wondering intently as to whether he himself has been such a man, or whether he is an incredibly astute observer and artist." Strong words, but I can’t say I agree.

Hubbard’s prose is the furious spewing of sentences that can only be replicated by those who know they’re being paid by the word. His style jumps between florid and perfunctory but never settles on something consistent, nor does the oddly languid pacing that forever feels at odds with the sheer glut of action unfolding in the narrative. A lot happens, but there’s little dramatic heft to it because the Lieutenant is ever so perfect. He’s the ultimate leader, ready for any situation and backed by a viciously loyal battalion willing to follow every order he gives. He overthrows a Communist government with absolute ease, and by the end of the novel is the undisputed and universally adored leader of England. Communism is bad but a dictatorship anchored by sheer charisma? That’s OK.

In 1989, the Scientology-affiliated publishers Bridge Publications, who now exclusively release Hubbard's books related to the Church, announced that a film based on the book would be made by the director Christopher Cain. This proved intriguing to me when I was looking for Hubbard books to try out since his work hasn’t exactly been popular for cinematic adaptations in the way his sci-fi contemporaries have experienced. The exception is, of course, Battlefield Earth, the making of which deserves its own article, but that didn’t exactly set the box office alight. That film was also funded independently and outside of the studio system, hinting at Hollywood’s unwillingness to get into the Hubbard business. Indeed, news of the supposed Final Blackout movie seems to have originated solely from Scientology affiliated businesses. I desperately tried to find news of this movie in the trades or even fan blogs and couldn’t come up with anything beyond the description offered by Wikipedia. Productions get canceled all the time, but usually, there’s a bit of a paper trail, and when you’re dealing with Scientology-adjacent properties, it’s hard not to get a wee bit conspiratorial about the whole affair.

Final Blackout is a novel of simple solutions to complex problems. It’s a world of chaos that imagines the most effective and beloved way to fix the world’s ills is with one charismatic leader who has all the answers. For everyone around said leader, blind obedience is required, even admired. One man controls all and anyone who offers alternative solutions is to be gotten rid of. I can’t imagine why readers would have a hard time separating Hubbard’s fiction from the beliefs of Scientology.