Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

The Thing Oral History: Cast and Crew Reveal Secrets of John Carpenter's Sci-Fi Horror Masterpiece

John Carpenter knows who was really the Thing at the end of the movie... but more than four decades later, he's still not telling.

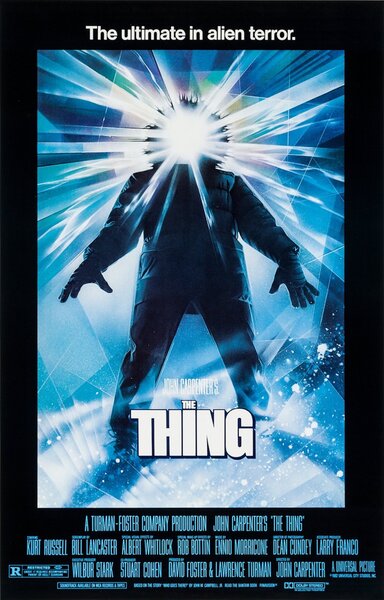

"The Ultimate in Alien Terror" was a mere promotional tagline in 1982. Today, those five simple words refer to one of the greatest science fiction horror movies ever made. One might even call it the greatest science fiction horror movie ever made.

It's hard to believe that 42 years have passed since the theatrical release of John Carpenter's The Thing (stream it here on Peacock) — which blended elements from 1951's The Thing from Another World (produced by one of Carpenter's biggest cinematic influences, Howard Hawks) and the John W. Campbell Jr. novella it was based on, Who Goes There? — to form an entirely new specimen that has been nigh-impossible to imitate all these years later.

A Definitive Oral History of John Carpenter's The Thing

Interviewees:

- John Carpenter (director)

- Stuart Cohen (producer)

- Larry Franco (associate producer/Norwegian rifleman)

- Alan Howarth (uncredited sound designer and composer)

- Dean Cundey (director of photography)

- Clyde Bryan (first assistant cameraman)

- Susan Turner (miniature designer)

- Peter Kuran (main title designer)

- Craig Miller (publicity consultant)

- Von Babasin (visual effects crew member)

- Keith David (Childs)

- Thomas G. Waites (Windows)

- Richard Masur (Clark)

- Peter Maloney (Bennings)

- Joel Polis (Fuchs)

- David Clennon (Palmer)

- Norbert Weisser (Norwegian pilot)

Carpenter's affinity for the material was evident in 1978's Halloween, which featured a scene in which Laurie Strode (Jamie Lee Curtis) and Tommy Doyle (Brian Andrews) watch Thing from Another World on television just before Michael Myers' murderous rampage throughout the neighborhood. That little homage might have remained the director's only connection to the property, had it not been for his old USC film school buddy, producer Stuart Cohen, who convinced him to take on the project.

"They wanted to put it into development, but weren't sure about John," COHEN tells SYFY WIRE over the phone. "He hadn't made Halloween at that point and they wanted to keep their options open."

"It was not something I wanted to do," CARPENTER admits on a separate call. "Universal had [the rights to] The Thing and they wanted to remake it. The original Thing was one of my favorite movies. I really didn't want to get near it. But I re-read the novella and thought, 'You know, this is a pretty good story here. We get the right writer, the right situation, we could do something.' So I decided to do that. This was right after Escape from New York. I had my first studio movie, which was a big deal."

The "right writer" turned out to be Bill Lancaster, son of Golden Age Hollywood star, Burt Lancaster. His only screenwriting credits up to that point were two comedies: The Bad News Bears and The Bad News Bears Go to Japan.

COHEN, who brought the film to Universal by way of fellow producer David Foster in the late 1970s, wanted to make "a thinking man's monster movie," he explains. "I said, ‘It's a movie where the characters are essentially indispensable and the better the characters, the better the monster.’ But we couldn't get anybody else to agree with that idea." He goes on to say he always envisioned it as a more faithful adaptation of the original novella. "The idea of disguise, the idea of the internal as opposed to the external. Plus the unity of time, place, and action is what fascinated me ... It was never about remaking the Hawks version."

After three failed attempts to realize The Thing, Universal finally relented in May of 1979 when Ridley Scott's Alien burst onto the scene and changed the face of horror-soaked science fiction. COHEN re-approached Carpenter, who once again refused. "He said, ‘You guys have failed three times. Why do I want to sign onto a failed project?'" Nevertheless, he agreed to revisit the source material before "reluctantly" agreeing "to develop a script," states COHEN, who later adds: "The Thing was John Carpenter's film, from the first frame to the last, but it was also a passion project of my own — a first feature expressly designed by me to make my entrance into movies after producing television at Universal."

"I think [John] saw something in the Who Goes There? idea that there is something and we don't know what it is, who it is, why it is," explains associate producer LARRY FRANCO, who first kicked off a professional relationship with Carpenter on Elvis (a 1979 TV movie about the hip-swaying rock legend, portrayed by Kurt Russell). "Is it us? Is it not us? I think that intrigued him and I think that was the basis for him saying, 'Yeah, I'd really like to remake that.’"

The Thing Special Effects

A tale of snowy isolation and creeping paranoia, The Thing follows a group of 12 men at an Antarctic research station who find themselves besieged by a thawed-out alien life-form capable of replicating any living organism. It wants to take them over and head for more populated areas until the whole world is absorbed.

CARPENTER: "We went back to the origin of the story, which is the imitation. It wasn't a big Frankenstein monster, it was a creature that can imitate other life-forms perfectly. It's a lot more complex and different than the first film."

The slow erosion of trust between the characters leads to in-fighting and violence as the alien, which can only be eliminated with fire, begins to pick them off — all while assuming a number of gruesome forms it has learned to mimic from a lifetime spent traversing the universe. The utilization of a frozen locale and horrific extra-terrestrial being of unfathomable origin may conjure up the cosmic dread of At the Mountains of Madness (published two years before Who Goes There?). However, CARPENTER insists that the comic horror made famous by H.P. Lovecraft was "not really" on his mind while making The Thing.

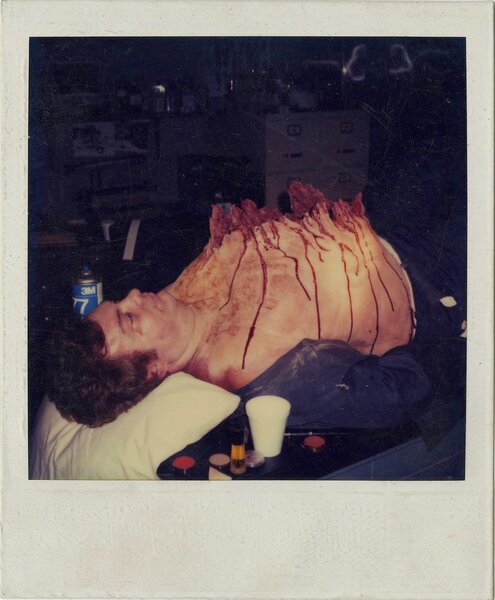

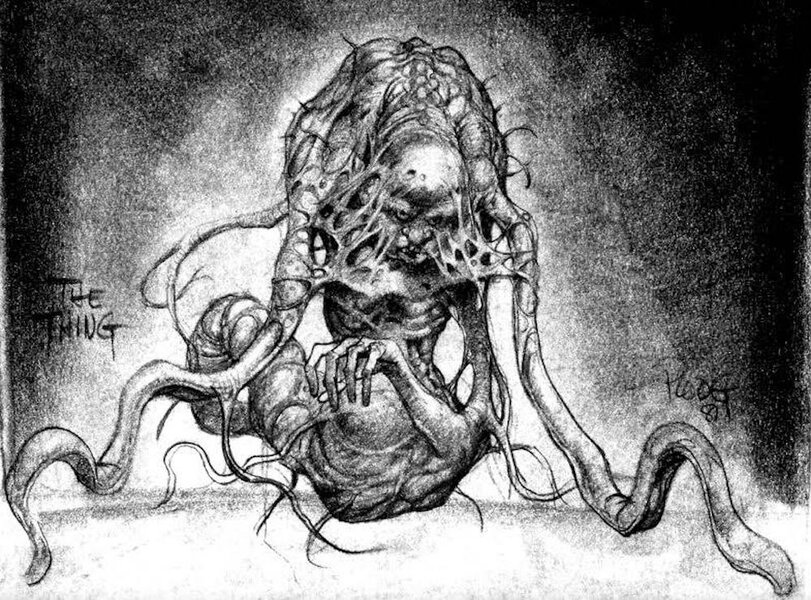

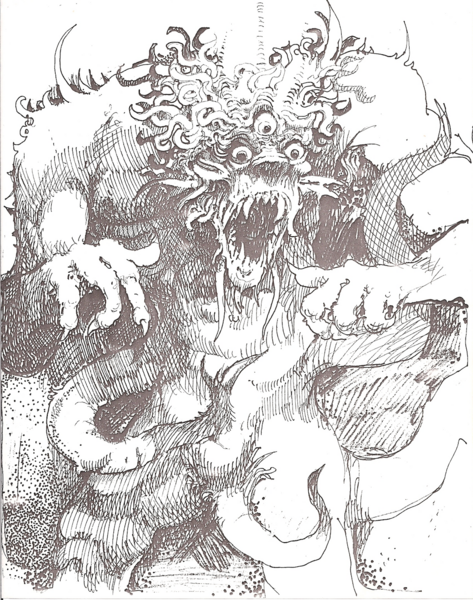

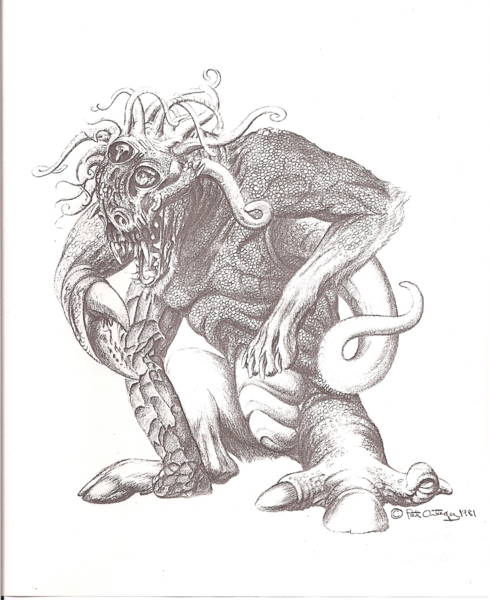

The effectiveness of the titular creature comes down to the incomparable work of Mr. Rob Bottin, whose trailblazing (not to mention nightmarish) creature designs set a new benchmark for practical effects.

CARPENTER: "[Rob] said, 'Well, the Thing can look like anything.' I thought about it and [came to the conclusion of], 'Well, that's true because it's been throughout the universe. Whatever it imitated, it can pull it up.' So why have one Thing? It's a constantly changing creature."

"We’re fascinated in [the idea] that something may not be exactly what it appears," says first assistant cameraman, CLYDE BRYAN, who first met Carpenter during pickups on Halloween and The Fog. "That original story, Who Goes There? [presents the] question [in its title]: Who’s there? Who are you? What are you really? I think you're something but maybe you're something totally different.' I think that story is enduring because … that’s the ultimate question. Not only who am I, but who are you, really? Because we all put on a little bit of a facade when we are with other people."

COHEN: "Rob was the smartest person on the production. Whip-smart. His organizational abilities [left something] to be desired, but he was a genius. During preparation, of all the things that needed doing, I think the one that John concentrated most intently on was the monster. Ahead of casting, ahead of production, ahead of locations. It really was about re-conceiving the monster."

A 23-year-old wunderkind, Bottin operated out of Universal's Hartland facility in North Hollywood, which had previously served as the home of visual effects crews for Buck Rogers in the 25th Century and the original Battlestar Galactica.

"Bottin didn't like the way the producers were always breathing down his neck," says VON BABASIN, a veteran of Jaws 2 and Airport '77, who worked under mechanical effects coordinator Roy Arbogast (he oversaw explosions, controlled set destruction, and the like) for seven months before moving onto Bottin's crew for another five to six months. "It was quite arduous for him ... So he negotiated this deal where they went over to the Hartland facility, which was a little facility in the middle of North Hollywood that didn't have the producers always there."

"Bottin was the one who pitched the idea that the Thing could be anything as opposed to just the one creature and Carpenter loved that," states ALAN HOWARTH, a veteran movie sound designer and Carpenter's longtime composing partner. "What Bottin didn’t realize, is he literally created an open-ended special effects task for himself. It was at a time when there was no CGI. This was all practical effects. It was goo and cables and puppets and stuff like that. Rob jumped into doing it ... staying up day and night."

"He was very passionate about his work," BRYAN says. "He was a definite individual that was unlike anyone else ... I liked Rob a lot. I don't think there's anyone that has the technical abilities to do the kind of stuff that Rob was doing at that time."

Bottin put in so much effort on this film, that he was briefly hospitalized for exhaustion. "He worked a little too hard sometimes, I'm afraid," CARPENTER adds.

HOWARTH: From Rob’s standpoint, it almost killed him and then at the same time, Larry Franco says, ‘We wanted to kill him!’ Because the whole movie depended on Rob’s stuff ... There was tension around those effects, which came out great in the end. But the filming of that stuff just went from simple to very complicated."

"There were times when he was just happy and jovial, and there were times when he was just under pressure and was not a happy camper," BABASIN says. Fortunately, Bottin had an encouraging 'support group' in Ken Diaz (special makeup effects coordinator), Vince Prentice (special makeup effects crew member), and Erik Jensen (special makeup effects line producer). "These guys were kinda like his posse and he was constantly surrounded by his friends, which was very supportive for him."

Babasin, who was only 28 during production, found himself inspired by Bottin's talent and work ethic. "To work with [him] made me want more out of myself," he admits. "Because here I was, 28, this guy's five years younger and he's got the largest special effects budget in history [$3 million]. I'm like, 'What am I doing?’ ... The guy’s a genius as far as his visual ideas and his creativity and sculpting and drawing abilities. It was pretty awe-inspiring to see him doing all this." As a "kind of assistant," Babasin found himself in the unique position of flitting between numerous departments. "I got to just bounce around."

And if the alien could look like anything, the reasoning went, then it could sound like anything, too. The creature's primal roars, insectoid chittering, and echoing cries cut right down to the bone, adding a ghastly dimension to Bottin's visual effects.

COHEN: "It was very painstakingly done by [supervising sound editor] David Yewdall. That involved a great deal of trial and error ... We brought the crew on early to begin developing the sound for a monster. Basically, the approach was one that King Kong used in 1933 [under] Murray Spivack, which was taking organic animal sounds and mixing them together and seeing what you got. We just took that to the nth degree. It was trial and error and when it fit, it fit. But it was a lot of effort ... I can tell you that the sound of the Blair monster is the roar [of] a lion and it's actually our tribute to King Kong. The others involved zebras…I forgot [what else]."

HOWARTH: "[Yewdall] came to me for a couple special sound effects because I had all the toys. Regular sound effects editors at the time had a Moviola and a transfer bay, but they didn’t have all the studio stuff. So I got involved with [Yewdall] in making the sound effect for the opening spaceship fly-over and then got involved in the whole dog transformation. Some of the dog material also wound up in the scene where the head pops out of the guy ... The technique was taking animal growls and grunts — whether it’s a bear, a lion, or a pig — and speeding them up or slowing them down down and then making other effects out of those sounds. I couldn’t tell you cut-by-cut what noises are what part of the creature. It’s just a melange."

Despite the fact that his adaptation would be vastly different from the 1951 version, Carpenter still wanted to pay homage to the OG movie by recreating its famous opening title sequence, in which the letters burn right through the screen. Not only would it serve as a love letter to one of his favorite movies, it would also hint at the brutal method through which the Thing takes over its victims by tearing through their clothes.

Bottin, who had just finished up work on Joe Dante's The Howling, suggested PETER KURAN of VCE Films for the job. A veteran of the first Star Wars movie and the Battlestar Galactica TV show, Kuran landed the gig by bidding $20,000, which was significantly less than the price tag proposed by Roger Corman's New World Pictures. Had Corman's company won the contract, The Thing's opening title would have been handled by an up-and-coming James Cameron. "I [can] actually say that I beat him out on a job," says KURAN, who accomplished the title effect with a number of everyday items: a fish tank, a garbage bag and some matches.

KURAN: "I eventually [landed on] a setup that had a huge fish tank, which I used to put smoke into. Behind that, I had a frame that I stretched garbage bag plastic over. And behind that, there was a 1,000-watt light being held back by the garbage bag plastic because [it] was opaque black. I put the title on the back of the fish tank using animation black ink in the cel to make the title. When I'd start the camera, I'd run behind and touch the garbage bag plastic with a couple of matches. The matches would make a hole; they would burn and open up and reveal the light, which then came through the title [making] the rays in the fish tank. We did several takes and got the one that we wound up using. One of the takes opened up and just said 'NG.' It didn't open up all the way."

Kuran's decision to use a fish tank was the result of a rather disastrous experience on The Wrath of Khan, which hit theaters the same year as The Thing. "I'd done a shot on Star Trek II [where] I used a salt heater and sugar to put together this effect. I did it inside and it just completely smoked out the whole building. So I learned from that and when I did The Thing, I put it in a tank, so that the smoke was in a tank [and] wouldn't go anywhere further than the tank."

The Thing's opening titles also feature a nod to the wider culture of 1950s sci-fi in the form of a flying saucer that crashes to Earth hundreds of thousands of years before the events of the movie. The ship was a miniature model constructed by SUSAN FRANK (née Turner).

FRANK: "[Peter] sent me over to speak with John Carpenter by myself and it was great. Carpenter told me his concept of what a spaceship should be like — he liked the '50s spaceships. He was very nice person. Very cordial [and] very supportive. So I went back, and I made it. We used motion control to film the spaceship in the opening sequence of The Thing, using different passes for the shots. One pass was the ship itself; two was the chasing lights on the perimeter of the ship; three was for the stationery lights. These different pieces of film were expertly combined by Pete Kuran in the optical printer with the matte painting of Earth by Jim Danforth and the 'exhaust flame' cel animation I created."

Turner still has the UFO model in her possession and hopes to sell it over the next couple of years.

The Casting of The Thing

With the creature designs and title sequence squared away, Carpenter set about finding his crew of frost-bitten men to populate U.S. Outpost #31: Kurt Russell (helicopter pilot, MacReady), Keith David (mechanic, Childs), David Clennon (mechanic, Palmer), Richard Masur (dog handler, Clark), Joel Polis (biologist, Fuchs), Peter Maloney (meteorologist, Bennings) Donald Moffat (station chief, Garry), Wilford Brimley (biologist, Blair), T.K. Carter (cook, Nauls), Richard Dysart (physician, Dr. Copper), Charles Hallahan (geologist, Norris), and Thomas G. Waites (radio operator, Windows).

Some of the cast (like Russell, Dysart, and Hallahan) were already established Hollywood veterans while others (like David, Waites, and Polis) were promising young graduates of Juilliard and USC. "Everybody had a character that they would play, but [it felt] natural and fit together," CARPENTER says. "I'm very happy with the cast."

CLENNON credits screenwriter Bill Lancaster with building such memorable protagonists in the screenplay: "He created these characters and gave them dialogue. I think that's why I wanted to do the film because I sensed on my first reading that the way these 12 men interacted, he had sort of elevated the form. I'm talking like a snooty-pooty pretentious literary critic of horror films, but I thought he had done a really fine job of bringing these 12 people to life."

MALONEY recalls his audition at the now-defunct Coca-Cola Building once located along New York's Fifth Avenue: "I went up there with a whole bunch of other guys [actors who were not ultimately cast] ... John led us in improvisation. We teamed up, turned the tables over, and threw things back and forth across the room, pretending that we were at war with this monster, which was, of course, not there. That was a fun audition."

CLENNON was originally up for the role of Bennings "because they thought I could play a scientist," the actor says. "I look like a kind of nerdy science guy. I got a lot of that [back then] and I said, ‘Yeah, okay, I'll go in.’ I guess I read the script, and thought, ‘Okay, I don't like horror films. I don't go to horror films. I'm too delicate. But there’s something about this script that is fairly interesting and it's based on a classic sci-fi [novella] that gives it a little literary class. So, yeah, I'll go in. But I also want to read for the part of Palmer because I think I could do something with it, even though it's against type.’"

He whole-heartedly agrees with our characterization of Palmer as a stoner, slacker, and conspiracy theorist rolled into a single package — not unlike the joints CLENNON taught himself to roll for the movie. "The big spliff was my idea. And in another scene, I was smoking from a little pot pipe. I had a little folding wooden pot pipe that I owned and used in real life, so I was using that on the set ... You brought up conspiracy theory [and] I would never have used that term to describe what goes on in Palmer's head. But you're right, that is a way of categorizing it. It’s a fantasy, it's Chariots of the Gods, it's an explanation of why the world is as it is in his mind."

While on the topic of Palmer, COHEN says that Bottin lobbied for the role, but was ultimately unsuccessful. "I put a stop to that, because he was way behind schedule. And, as I told him, ‘We’re after actors for this, who can bring a lot with them to the roles. You don't have the time and you're not going to do it.’"

MASUR, meanwhile, was first interested in the role of Garry, but ended up choosing Clark after reading the script. "I said, 'The thing that I'm most attracted to is the dog handler.' [John] said, 'Really?' I said, 'Yeah, I love this character. I just think he's so misanthropic. He doesn't seem to want to be with anybody, but the dogs.' He said, 'Well, it's yours, if you want it.' And that was it."

To prepare for the role of Fuchs, POLIS approached his character by enrolling in a beginners biology class at New York's Baruch College: "We dissected a frog and I just got into it."

DAVID says he viewed Childs as "the strong, silent type. He was a man a few words, he didn't say a whole lot. But when he did, it counted. I just took took him as being [a person] who observes and notices everything at least twice."

A method actor by nature, WAITES went pretty deep on the character of Windows (originally called "Sanchez" in the screenplay, per Cohen), which drew a bit of teasing from his fellow co-stars. "Kurt and Wil Brimely — God rest his blessed soul — used to make fun of me and say, 'What are you guys doing? Discussing your motivation?'"

He continues: "I was trying to find something about the guy, who he was and what his dreams were. Did he want to work in a f***ing radio station in the Arctic for the rest of his life? No, he had to want to be something else. So I have him reading — I know this is very subtle — a Hollywood magazine with pictures of famous movie stars from the time on the cover. Because that's what he wants to be doing, to be in the movie business and be a movie star. And movie stars wear sunglasses. I picked up a pair of green sunglasses in Venice [California]. I was wearing them [when] I came into rehearsal, I kept them on, I read the character, and I went up to John on the break. I said, 'John, from now, from now on, I want everyone to call me Windows.' He looked down at the floor, he looked up at the ceiling, took a long drag on the cigarette, and put the cigarette out. You could see him thinking it through and he went, 'Alright, everyone! From now on, Tommy wants everyone to call him Windows, okay?'"

This apparently drew some backlash from Moffat and Clennon: "They're like, ‘This is f***ing bullsh**, man! This is so arbitrary! What are you doing, letting him call himself Windows and wear sunglasses inside?!’ John…I don't think he gave a f*** what they said. I think they only said it to me. I think they ridiculed me because they thought I was just doing it to get attention. But I really wasn't."

MALONEY: "Donald Moffat ... didn't want Tommy Waites to wear those sunglasses through the whole movie and he didn't want to have to call him 'Windows.' That was a last-minute change around the table. Tommy said, ‘I think my character wears sunglasses all the time and should be called Windows.’ John said, ‘Okay!’ And Bill Lancaster, who was there with us during those weeks, said, ‘Okay!’"

According to COHEN, everyone hated the name "Windows" outside of Waites and Carpenter. "I thought it was an old Howard Hawks thing and that we were going to end up with characters' names from a lot of different Hawks films," the producer admits, going on to add that the runner-up for the part of Windows was none other than Chucky himself, Brad Dourif.

A fun little aside: The Thing features a pair of characters named "Mac" and "Windows" long before the advent of personal computers.

"Maybe We're at War With Norway"

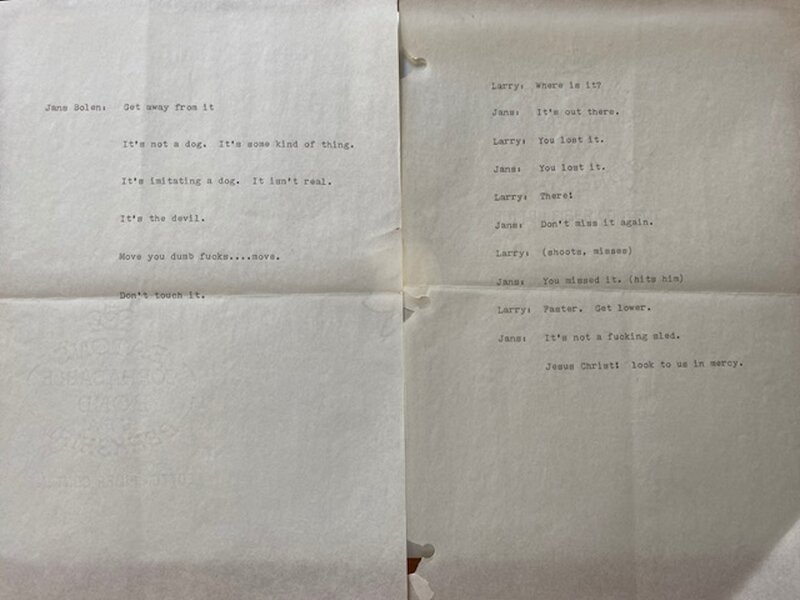

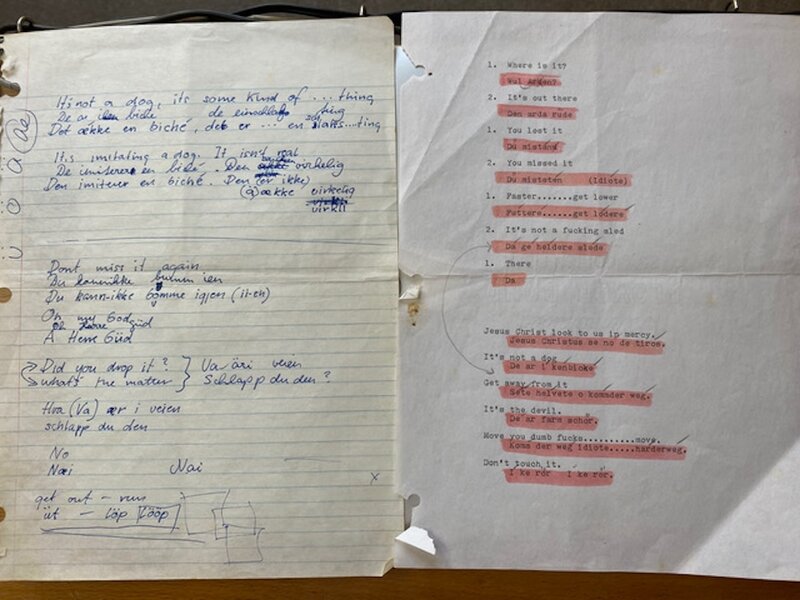

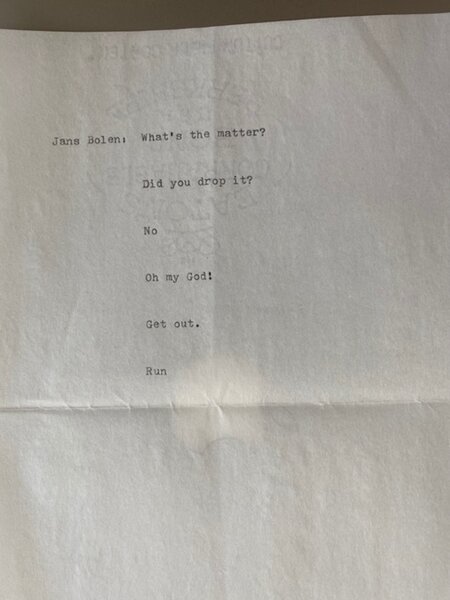

Beyond the main group of characters, Larry Franco and Norbert Weisser briefly co-star as the two Swedes...sorry, Norwegians, who try and fail to destroy the Dog-Thing before the infection cycle can begin anew. Weisser, a native German, got the meatier part as Jans Bolen (his name is revealed in a deleted scene), the ranting helicopter pilot attempting to warn the Americans about the dog's true nature before he's shot and killed by Garry. His warning translates into: “Get away from it! It’s not a dog! It’s some kind of Thing! It’s imitating a dog! It isn’t real! It’s the Devil! Move, you dumb f***s! Move! Don’t touch it!”

WEISSER: "I was invited to meet John. It was just him and me. We just sort of talked and shot the sh**. A few days later, I got another call to come in [because I’d gotten] the job, just by talking ... John gave me the English … and I had to figure out [how to say it in Norwegian]. It was essentially, 'Figure out how to get the language.' So I ended up going to a friend of mine who was a Russian teacher at UCLA, and he had a friend who was a Norwegian. I had him say it, I taped it, and then I wrote it down the way I heard it."

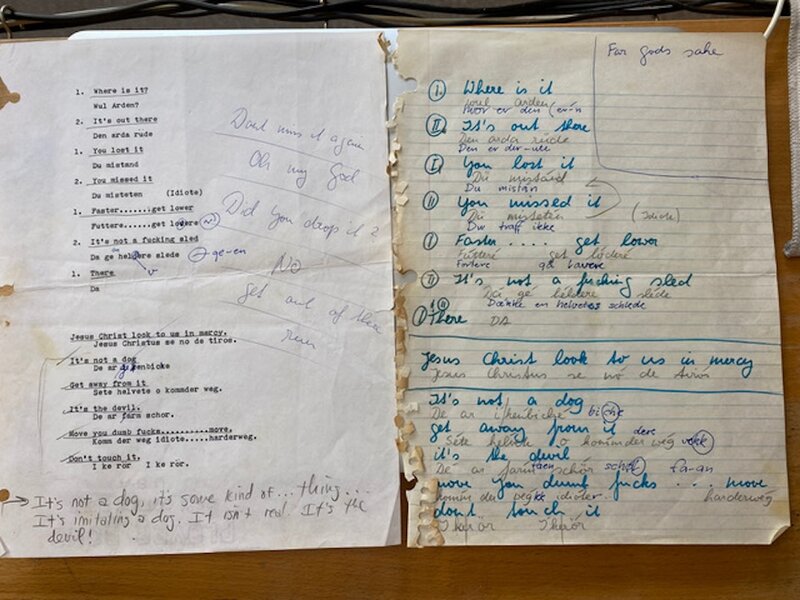

Interestingly, the script originally featured a brief bickering match between the two Norwegians throughout the helicopter chase, but the conversation was never shot. Weisser, who still has his original copy of the screenplay (no, he's not interested in selling it), was kind enough to share those lost pages of dialogue with us. The exchange is as follows:

LARRY: "Where is it?"

JANS: "It's out there."

LARRY: "You lost it."

JANS: "You lost it."

LARRY: "There"

JANS: "Don't miss it again"

LARRY: (shoots, misses)

JANS: You missed it (hits him)

LARRY: "Faster. Get lower!"

JANS: "It's not a f***ing sled."

Before production began in earnest, Carpenter insisted on two full weeks of rehearsals (a highly unusual occurrence for a big-budget studio movie like The Thing), which took place on an empty Universal soundstage. "It was just having the actors get comfortable with their roles and with each other," CARPENTER says. "It was very, very valuable. There really wasn't wasn't much more than, 'Let's go through this, fellas.' They worked out a couple things and they worked out their characters."

Cohen asserts the rehearsal process idea originated with him and was partly used as "a sales tool" to assuage skittish agents who didn't want their clients "playing second fiddle to a monster."

COHEN: "We had difficulty securing the people we wanted to initially meet and it was only when I got them to read the script that they began to understand what we were up to and how well the characters were developed. It’s a process John never repeated. I'm not sure he loved it at the time. I think he felt that it gave the actors too much power. But he did it and here it made sense."

POLIS: "We really established relationships with each other and I think that comes through in the film. When we finished filming, John famously said, 'I'll never rehearse actors again.' But 40 years later, I'm told — I don't know if it's true — but I think he thinks it was his best film. And I'm sure it's because of the relationships."

MALONEY: "[We'd] take the time to talk about the script and offer ideas [and] those of us who would like to do research did research, brought it in, and shared it with everyone. Then we wrote things on the board [and] learned a lot about what it's like to be in the Antarctic."

CLENNON states that the rehearsal period was marked by a number of "metaphysical" conversations about, 'Do you know when you have become the Thing?’ and stuff like that. I thought, ‘It doesn't matter. We're making a movie.’ What matters is that the audience doesn't know who’s the Thing. To speculate about whether Palmer knows he's the Thing after he's been absorbed by The Thing and how that’s going to affect his acting is metaphysical bullsh**."

"I Don't Know What the Hell's in There, But It's Weird and Pissed Off, Whatever It Is"

During this period, Masur spent a lot of time with the dog — a half-wolf mix named "Jed" trained by Clint Rowe — that gets chased to U.S. Outpost #31 by the Norwegian helicopter. "Jed was just remarkable," says MASUR, who practiced with the canine for hours until the two could walk "in this totally casual way" down the hall leading to the kennel. "I love dogs," he adds. "I always have." Shortly after the lights go down, the seemingly docile animal reveals its true nature and begins assimilating the other dogs, prompting Childs to burn it with a flamethrower.

DAVID: "Everybody always thinks it's so sexy and exciting. It was scary. It wasn't napalm, but it was real gasoline coming through a real pump and a real gun [producing] real fire. A slip of the finger could cost somebody their life or certainly lots and lots of damage. So, it was a little scary. I was excited and glad to be doing it, but it was a little scary."

BABASIN constructed a small corner of the kennel ("everybody was so busy at Hartland at one point, that they actually bumped me up to prop maker," he recalls), which can be glimpsed in the 4-second shot where one of the poor, half-melted canines gets wrapped up in tentacles. "We mounted the dog there, we wrapped him up in tentacles, and just K-Y’d the heck out of him. K-Y Jelly was everywhere. And on ‘Action!’ everybody grabbed a tentacle and ran with it. They were hard rubber tentacles; as they stretch, they got smaller. By the time they really stretched, the tentacles all slipped away and let go of the dog. You reverse the photography and the tentacles just dive into this dog and wrap him up. Every time I see that, I go, ‘That’s my corner of the kennel!’"

FRANCO: "I can remember ... that dog's mouth splitting open and the mechanics that went into that; watching those people spend hours trying to figure out how they were going to do that. You really had to pull stuff out of your butt to make it work. At the end of the day, people might look at this and say, ‘That was the last great makeup special effects [movie].’ Forget visual effects, because there weren't any. There was nothing in that movie that was touched by a computer to fix later. It was either there or it wasn't."

The iconic scene was initially conceptualized by artists Mike Ploog (best-known for co-creating Ghost Rider and Werewolf by Night at Marvel) and Mentor Huebner (whose cinematic work included Forbidden Planet and Blade Runner). "[Huebner's] conceptual art actually more closely matched what we finally saw on screen than almost any other conceptual drawing I saw," notes BABASIN.

This set piece was so convincing, in fact, that it caught the attention of The Humane Society, which thought the crew was "doing terrible things to real dogs," says CRAIG MILLER, a publicity consultant who worked on The Thing, The Hitcher, and The Last Starfighter. "We had to bring them in and show them the mechanisms, so that they would get it wasn’t real."

MALONEY, who had a terrible fear of dogs at the time, also needed to spend time with Jed in order to feel comfortable enough to let the dog jump up and try to lick his face near the start of the film. "When Jed stood up and put his paws on my shoulder and licked my face, he was taller than me, I think. I was pretty freaked out by having to do that."

Clark's hunting knife, which makes an appearance during the scene where Garry cedes command to MacReady, was completely Masur's idea. He went to pick it up on one of his lunch breaks and accidentally cut his thumb.

MASUR: "It just started bleeding like a stuck pig. I was in my costume and I take my hat off and I'm holding it against my thumb. I drive like this over to this emergency room, which was not too far away. I walk in, I'm sitting and I'm like, ‘I have to have somebody look at this right now. I gotta get back to work.’ And they said, ‘Well, you gotta wait’ and I said, ‘I’m bleeding like a pig here!’ So the guy looked at it, he put a butterfly [bandage] on it — it didn't need a stitch — and he got it to stop bleeding. I went back to work and forget what I told wardrobe. I [I think I] told them I dropped it in a puddle or something [like that] because it had blood on it, but it was dark cap, so you couldn't really see it."

Principal Photography on The Thing

Once rehearsals were over, the shoot finally commenced, with Carpenter's trusty cinematographer — the legendary DEAN CUNDEY — back at his side after Halloween, The Fog, and Escape from New York.

CUNDEY: "We didn't remove walls from the set, so we could back the camera up and get wider shots. We shot everything as if we were actually there and I think that gave a sense of reality to the environment. I made sure that the lighting came from the practical lights that hung overhead in the set ... I also think it was because the creature, in its various forms, was on the set. It was not a tennis ball on a stick, as so often it is nowadays. It was, in fact, something the actors could see, touch, feel. I think all of those authentic touches created an atmosphere — not only for the actors, but also for the crew."

The biggest challenge was shooting Bottin's creations in such a way that they felt alive and took "advantage of textures and gooey slime and all of the stuff we used to give a sense of weirdness to the creature," the DP explains. "So it was all carefully done. Rob [would] set up the creature, would point and say, 'Okay, I hate this area, let's not look at that too much. This [area] came out okay.' And so, I would very carefully light with little pools of light and darkness for the creatures that he built in an effort to show off their best aspects, their strengths. Rather than the audience looking at something too big and saying, 'Oh, well, that looks like a blob of rubber to me.'"

CARPENTER: "We didn't go to computers because they didn't really have them back then. They didn’t have it perfected and I'm happy with the way it looks. It's fine as it is. I don't see why you’d change anything."

MASUR: "We are the last of the great rubber movies. After us, things started going pretty much all CGI for these kinds of effects. But Rob Bottin got to do the Mona Lisa/Sistine Chapel of rubber. And it's pretty impressive, I gotta say."

TURNER: "It's an important film for being one of the last films that was made with all the old techniques."

COHEN: "The Thing is one of the last great analog films, made on the cusp of the sea change from chemical to electronic. It was made the old-fashioned way with no video assist or electronic monitoring to aid its director. You processed the film and showed up the next day to see the results. Sometimes, in the case of the opening chase on the Juneau Icefield — which was filmed with a small second unit — the film was sent down the coast for processing. Incredible? Not really. There was no choice. It's simply how things were done. Same with all of Rob’s stuff. We'd shoot it and show up the next day to see if it worked. Sometimes it did."

FRANCO: "Nowadays, you can just go in and fix anything. Back then, there was nothing you could do. Once it was there, it was there. And if it worked, it worked and if it didn’t, you had to do it again. Sometimes that was two or three hours later. So there was always the challenge of ‘Okay, what are we gonna do when this breaks down?’"

Before the shoot kicked off in earnest, though, the crew attempted to get some early helicopter footage for the movie's famous opening (where a pair of members from the Norwegian camp attempt to kill the Dog-Thing) with an approximation of the desolate Antarctic tundra on the Universal backlot. Per Babasin, Stuart Cohen refers to this as "The $40,000 Mistake."

Over the course of three-and-a-half weeks, the crew converted "this hill above the dump in the backlot" into a wintry biome via "white sheets of muslin, and 100-pound bags of gypsum," as well as "fiberglass rocks," BABASIN reveals. A trio of "miniature" remote-control helicopters 10-15 feet in length were constructed to fly across the phony landscape, except all three of them encountered problems. One bumped into a rock and crashed; the second exploded by accident; and the third simply "didn't fly right." About a month of work and $40K went down the drain in just a single day.

BABASIN: "John just turns around to the crew, leans against the bar and says, ‘Okay, folks, that's a wrap!’ And that was it. From what I understand, they actually did get a few frames of Number Three. But like I said, Stuart Cohen does not like to relate that story. People rarely like to relate stories of failures, but there's a lot of that in filmmaking. It's trial and error. Even the greatest effects guys of all time have tried things that have failed."

Most of the chase ended up being a practical set piece, with around a dozen crew members (including Carpenter, Franco, Cundey, Bryan, Cohen, Clint Rowe, and Jed) shooting it on the Juneau Icefield in June 1981.

BRYAN: "We shot it in the summer before we even started production ... that's why you see a few pictures of everybody shirtless on the ice field because it would warm up to like 60 degrees and was too hot to wear all the clothes we had on."

FRANCO: We were in a geological camp and there was only room for 12 of us ... In the one week that we were there, we had the most fun. I swear, it was one of those things where [you've got] 12 guys out there, plus I think we had three or four camp people to help make sure we didn't fall through the ice. But the 12 crew people were really grinding it out in the snow and just having a blast."

Filming then moved to Universal's soundstages that were constantly kept refrigerated in an effort (the exact temperature varies on who you ask) to simulate the Antarctic setting. In addition, the crew needed to figure out a way to create visible breath when the actors spoke their lines.

FRANCO: "Our guys calculated that at 42 degrees, with enough humidity in the air, we could create the breath. So the sound stages were air conditioned down to 40-something degrees. [We had] these big burlap sacks hanging from the ceiling that had water dripping on them, so [we] could create the humidity in the air. And when we got there every morning, it was right on the money. By the time all the lights came on and we started shooting…before we broke for lunch, we had no breath anymore because the stage had heated up to the point where it wasn't working."

He continues: "When they come upon the block of ice with the Thing in it [at the Norwegian camp], that was a very challenging thing, too, because that ice kept melting. We couldn't keep it cold enough. When you think about the practicality of pull something like that off... but in the end, it all worked great."

POLIS: "It was cold in there and so, I had the costume designer make a woolen neck warmer, which I wore in the movie. And in a week's time, the whole crew was wearing neck warmers."

BABASIN: "We had to try to make the stages as cold as we possibly could with air conditioning units and spraying misters in the air to try to get the visual of the breath coming out of the mouth. We would be all dressed up in these parkas and looking like we were in Antarctica then walk off of the stage to go outside, and it was 100-degree weather. The Universal [studio] tour trams would drive by and they'd go, ‘My god!’ We must have looked crazy walking off the stage in all these these jackets and everything in the middle of a summer in L.A."

MILLER: "It was very hot in the San Fernando Valley and, of course, the stages were being chilled down to where frost could be seen coming out of the actors’ mouths ... so many people were getting sick on the production, being on the stage at — I don't know — it must have been down in the 30s, certainly no more than the 40s. It was over 100 degrees outside at the studio. So going in and out between the two took its toll on a lot of people."

COHEN: "The first day I got sick. It was 37 degrees inside and 106 outside. The crew inside, wearing parkas all day, was okay. I was going in and out, throwing my jacket off and then throwing it back by going inside and I came down with the flu by the end of the first day. I was not the only one. The crew ended up trading colds and the flu back and forth ever since Day One."

FRANCO: "The physical part of [having] 100-degree weather outside and walking into a 40-degree soundstage and putting all the gear on that you needed to have inside and then taking it all off to go outside...going to the bathroom became more than we wanted it to be."

WEISSER spent his first day of work on the backlot pretending to be a corpse. "I had all day just talking to people, cast and crew," he remembers. "By the time I'm on to play dead, I am jacked up on — I don't know — 50 cups of coffee. I could barely keep my body still. I walked away from that feeling devastated. I told myself, ‘You can't even act a dead guy?’ It was really a matter of keeping my entire body still. I now know what I should have done is just relax. Playing dead is not easy. In any case, I pulled it off, because it's in the in the movie. But I remember driving away from Universal Studios feeling like a schmuck."

Exteriors were then filmed on the Salmon Glacier up in Stewart, British Columbia (near the Alaskan border), where a life-sized research station was erected. The crew then allowed the snow to accumulate for several months before making the journey north. "We bit off more than we could chew, but we did pull it off," FRANCO says. "That’s one of the things that lives with me, is, ‘Man, oh man. How do we go up to British Columbia and end up on a glacier and build a set and actually shoot the movie?’" It was a breathtaking spot, alright, but the weather never stayed consistent. White-outs, overcast skies, and below-freezing temperatures never failed to wreak havoc, especially with regards to visual continuity.

CARPENTER: "Once you get a cloud or clouds overhead, then everything goes white. And we had to match the skies, which were clear and beautiful, so it was a pain. It was a mountain that we had to go up. We were down by the bottom of the mountain and then we had to travel up every day. We'd get up there, the weather would be sh**, we'd have to wait all day long, get nothing done, and then go all the way back down ... We all were in it together. It was not an easy film to make. We had to fight the elements. It was rough. And since we were all in it together, we all bonded. Everybody bonded."

FRANCO: "We all had these wardrobe-issued parkas with hoods on them and big furry things in the front. I got onto the set, turned around, and everybody looked exactly the same. There was no way [to] tell who everybody was, so we ended up putting name tags on the back of the jackets."

WEISSER was only supposed to fly up for a couple of days to film his Norwegian rant (and subsequent death), but ended up staying for the duration of the shoot. "The establishing shots were done in sunshine and then the sun went and never came back. So I stayed through the entire outside shooting ... And then, on the last day, they finally had to say, ‘Okay, we'll shoot it without the sun.’" Mistaking the crazed Norwegian for a homicidal madman, Garry neutralizes him with a direct shot to the eye. "You saw the mask that I have on," he adds. "They had a piece of metal underneath, and then an explosive with chicken guts [and a fake eyeball] above it. The explosive then blew the ball and the chicken guts out of my eye."

POLIS: "I've backpacked all over the United States and so, I love the outdoors. I was in heaven. It was an adventure. "T.K. Carter hated it. He was used to LA, he had never been in that kind of cold. And some other people didn't like it very much. But man, it was so beautiful up there and we had all these great toys: helicopters, flame-throwers, and all this sh**. It was like a kid's dream come true."

Another unforeseen roadblock was the fact that the weather atop the mountain was too dry, which meant the actors' breaths would not show up on-camera. "It's really, really cold, but it's not humid," explains BRYAN. "And so, there was a lot of drinking of hot beverages and stuff to make breath on some of the scenes."

At the end of many rough, yet rewarding, work days, the gang would unwind in the Alaskan town of Hyder (right next to Stewart) with plenty of free-flowing Everclear to keep them warm. "That became a hazing or a ritual that we put ourselves through," remembers WAITES, who is now a recovered alcoholic. "We did a lot of drinking and a lot of partying. It was burning the candle at both ends — staying up all night and having to shoot all day. It was the ‘80s, man. It was a different time."

WEISSER: "We drank way too much, we went on sled rides, we did all kinds of crazy sh**. There was a place where you got 'Hyderized' in Hyder. It was a bar and in order to get hide 'Hyderized,' you had to drink a shot of pure, grain alcohol. Not a couple of sips, but down [in one go] and then you got a little card that said, 'You are now Hyderized.'"

BRYAN: "Pretty much everybody in the cast got 'Hyderized.'"

Of course, not everyone partook in the merriment. "Donald was a family man and [became] upset when we would come in at three in the morning, drunk from the bar and wake him up," states POLIS. "But he was a good man and a wonderful actor."

While the cast and crew often frequented Hyder to get their party on, the main lodgings were in Stewart, though not everyone got to stay in the comfort of a hotel. "There wasn't enough housing ... we ended up bringing in these big logging barges" FRANCO says. "I think we had two of them and these barges were no-frills, trust me on that. We had crew living in there. The cast, John, myself, and a few other people lived in this hotel called the King Edward. It was also no-frills, but at least it was dry and warm."

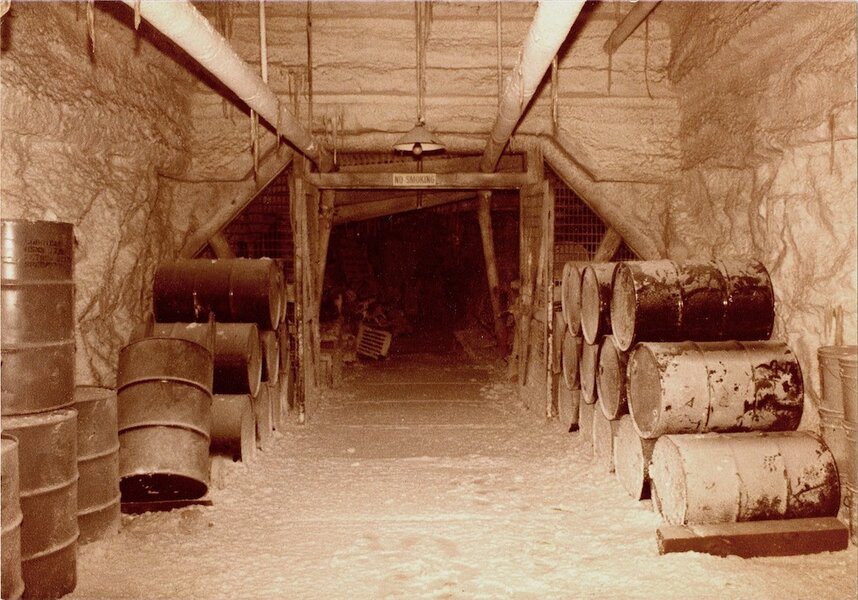

Getting cast and crew from Stewart to the glacier — and back again — proved to be "one of the most difficult" aspects for FRANCO, who mostly dealt with logistics. In the end, the production settled on a mixture of on-road vehicles and helicopters, the former of which required the filmmakers to establish radio communication with a copper mine operating on the same mountain.

FRANCO: "They had these ore trucks going back and forth up the hill. When they're coming down the hill, they have a full load and they're very heavy. You have got to stay out of the way of the trucks coming down the hill. We would be riding up in a van and you would hear over the radio, 'K-55, south at 14,' which meant a K-55, a heavy loaded dump truck, was headed down the hill. There were mile markers everywhere and there were only a few places that you could pull out. So if you heard 'K-55, south at 14,' and you were at South 15, then you knew in one mile, there was gonna be a truck coming down doing 20-30 miles an hour. But there's no way it's going to stop on this one-lane road really, except for these pull-outs ... That was kind of exciting and challenging, because it was always in the dark. We’re going up in the morning, in the dark, and we're coming back in the evening. Coming back wasn't so treacherous, because the trucks were empty coming up the hill. We knew that they were coming north and we were going south. We always knew where these trucks were all the time. There were a few people who got a bit scared of that whole thing, but we managed that."

WEISSER: "I'd fly in [to the set] with a helicopter. Some other times, I would drive in. It was maybe 50-50. We flew between two steep mountain walls and there was a glacier. We flew high enough not to hit the glacier. One evening, we flew back. There was still sunlight and we were joking, being funny. All of a sudden, we hit a white-out. We flew right into the fog. The helicopter is now between these two walls, we’re still joking around, and the helicopter pilot said, ‘Silence! Be quiet!’ We realized, ‘Oh sh**.’ He was trying to get above the fog without hitting the wall on either side. It was quite a moment."

Despite the glacier's uncooperative climate, Carpenter wanted to make full use of the location and went so far as to move a number of scenes outside, "which, to my mind, just defied the whole premise of the story, which was, 'We can't go outside unless it's an absolute emergency,'" argues MASUR. "After I saw the film, I thought John had made a good decision. So that big scene at night where Kurt's going, 'I know I'm human' and burning the blood bags and everything. We [originally] shot that all inside in the rec room and it was a great scene — it was really tense and crazy. Then John moved it outside and we're standing there in a line in the cold."

POLIS: "Originally, he had me killed on the set indoors. I've got a great picture of me hanging from the door with a shovel in my chest. He took a look at it and went, 'No, no — this isn't a slasher movie.' And so, he devised [a new and ambitious death]. He actually gave me like five or six extra scenes when we went up to [Canada]. He wrote them for me, because I became the bridge to the science."

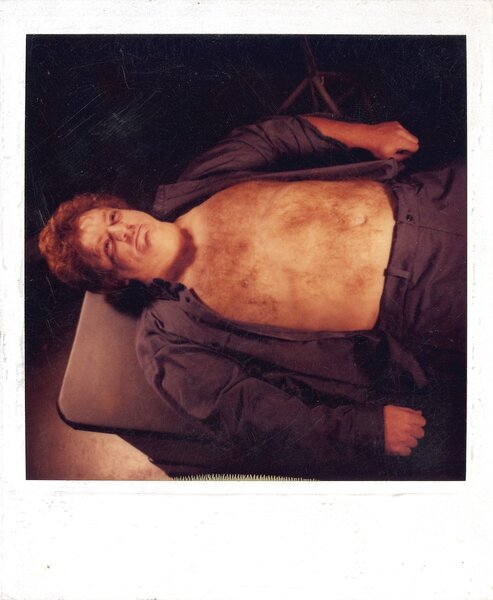

Another memorable sequence shot in the blistering cold was the death of Bennings, the first member of the group to be assimilated onscreen when he's briefly left alone in the storeroom with thawed-out Thing remains. "If you see the movie and you see anybody with a beard like me, then you know that that person is not going to transform in the face," MALONEY says. "Because with with facial hair, it’s too difficult to make the [special effects] cast. The creature barely gets to finish the absorption process when Windows returns, forcing the Thing masquerading as the meteorologist to make a run for it. The monster doesn't get very far when it's burned to death by MacReady.

"I had no shirt on, my coat was wide open, and with the wind-chill, it was 103 degrees below zero," MALONEY recalls, adding that the only source of warmth came from a pair of hand warmers stuck inside the false arms. "John said, 'Well, look, the cameras are going to maybe slow down here [because] it is so cold. I'm putting you in charge. If you feel that it's dangerous or it's too uncomfortable, you just tell me and we'll go back inside and warm up.' I don't remember asking him to do that. Actors want to please the director and sometimes, they can put their lives in danger because they want to do what the director wants. And we all want the movie to be terrific. We don't want to chicken out and deprive the movie of a scene that might be terribly thrilling to the audience."

The subsequent scene where Garry laments the death of his friend, Bennings, was the result of the aforementioned rehearsal process.

MALONEY: "I remember Donald saying, ‘Well, you know, Bennings is my friend. Why in the story do I not express my anguish at what we've just done to Bennings?’ Which was see this man overcome, the first one in our group, to shown signs of infection from this terrible virus. Then we we kill him, we soak him with gasoline, we light a flare and we stand around and watch him burn, like a Tibetan monk protesting the war or something. It’s a horrific ending. Even though I’m half-monster, half-human, I plead not to be killed with that strange bellow that comes out of me as I turn to look at Kurt before he throws the torch. Donald didn't know why his character was not expressing the human emotion that one would express if a good friend suddenly was killed ... And so, there was something written in there. Bill and John were very attentive, John especially, to what we needed."

CLENNON expresses a similar sentiment about Carpenter: "If an ad-lib worked, he’d use it. He wasn't real strict about sticking to the script." For example, Palmer's "Thanks for thinking about it, though" line was not in the screenplay, but an eleventh hour suggestion from Clennon's friend, the late Don Calfa. "I say, 'I'll take you up there, to the Norwegian camp, Doc! I'll fly up there!' And our captain, Garry, says, ‘Forget it, Palmer!’ Don Calfa said, ‘When he says that, try saying: Hey, thanks for thinking about it, though.’ He's a little out of touch and Garry just sternly, scornfully dismisses his idea. ‘Hey, thanks for thinking about it, though.’ Like, as if the guy had actually thought about it. And that line stayed in the film. It was ad-libbed and it was a gift from the late Don Calfa."

Another bit of improvisation can be found in the scene where Palmer and Childs smoke a joint and watch pre-recorded episodes of Let's Make a Deal. This brief, slice-of-life moment may seem irrelevant to the larger story, but it really hammers home the profound isolation and monotony these men face every single day.

CLENNON: "I thought, ‘Look at the level of boredom that these guys have to contend with.' ... I thought, ‘Palmer, in his stoned orientation to the world, maybe sees these game shows as dramatic structures.’ It's like you're watching a movie and you're stoned, you’re loving it, and you're watching this thing unfold before your eyes. It's a drama, they create this drama around a game — partly a game of chance and [partly] a game of guesswork. And so, he sees it in those in dramatic terms.’ I thought, ‘I’m going to put one in the player and then I'm going to reject it, saying, Nah, I know how this one ends.’ I thought, ‘Well, that's a stoner approach to life. I don't want to watch this game show again because I remember how it ends. Give me a few months, maybe a few weeks, and I'll forget it [and] it'll all be new to me and I'll be surprised by the way it plays out.'"

To compensate for the freezing environment, CUNDEY had the cameras "winterized," a process by which the manufacturer (in this case, Panavision) replaced the usual lubricant with an anti-freezing agent. "We [also] had a warming system for the the magazine on top of the camera that held all the film to keep the film from freezing and cracking and buckling. Keeping everything warm was an important thing." However, if the cameras were brought inside during breaks, the lenses would fog up with condensation from the temperature differential. "Pretty quickly, we decided that the room with the camera work always had to stay the same temperature as outside, below freezing. So the poor camera assistants never got a break to go into the warmth while they were working. They would go into the below-freezing camera room and they would work in their big parkas and their gloves and everything."

BRYAN: "I had to prepare all the camera gear to work in the cold. It was it was a quite a chore to get those lenses to work in the freezing cold. The oil inside the lenses that lubes the focus and stops had to be changed because the stuff they generally used would freeze. We also made homemade heaters around the lenses because they would be so tight, that you literally sometimes couldn't pull focus. We were fortunate to work with Panavision in Vancouver. They they had battery eliminators, which were a way to run the cameras on an electrical current instead of a battery because, as we all know, batteries don't like cold weather. They would have about a quarter of the life that they normally had. But we were able to tap into an AC current and run the cameras through that with an inverter."

With regards to color, CUNDEY leaned into the idea of contrasts: "[For] the interior of the of the camp, I would tend to light it with a slightly warm light, implying that where they were living and working was kept warm compared to the exterior [which] tended to be blue. Sometimes, light coming from the camp would be warm so that we could say, ‘Oh yeah, that's warmth and safety over there' ... Blue tends to be something we associate with cold and freezing, as opposed to warm light that we associate with fires and sunny days."

BRYAN: Dean’s lighting of The Thing in all of its renditions is pretty masterful in the fact that you have to see it, but you don't you can't see too much. You can't see too little either. Rob was always saying, ‘You can't see it!’ And Dean was saying, ‘Yeah, but I see too much. Because if I see too much, I know what it is. It's a rubber model that's not real. But if we hide enough of it, the audience is going to believe it's real.' Eventually they think came to terms and figured that out. I just saw it a little over a year ago in a theater for the first time since it first came out … I had forgotten that John employed so many close-ups in the making of that movie, because it's really about what's happening in everybody's heads."

That Time The Thing Cast Nearly Went Over a Cliff

Tragedy nearly derailed production when a bus carrying the entire cast, all of whom had just arrived in British Columbia, almost fell off the the side of a mountain somewhere between Prince Rupert and Stewart (approximately a six-hour trip), where the actors stayed for the real-world leg of principal photography. As Polis recalls in this 2016 interview with the Halloween Love blog, they were originally supposed to fly between the two locations, but due to inclement weather, they took a bus instead. This didn't turn out to be such a good idea either once a whiteout suddenly hit in the middle of the night. His co-stars share more details with SYFY WIRE below...

WAITES: "I’m back there, drinking beer and smoking pot and partying, because we’ve got a six-hour bus drive, man. And we hit a whiteout. Kurt goes to the front of the bus and he's like, ‘Are you going to be able to get through this?’ The guy’s like, ‘I don't know. I don't know.’ And all of a sudden, we skid and the f***ing left back axle is hanging off [the edge]. I don't want to tell you what was down below because it was thousands of feet of ice and rock. All of a sudden, we realize we're in f***in' serious trouble."

WEISSER: "One wheel was hanging over the [edge]. If we had gone down there, we would have been dead ... That would have been the end of the movie."

DAVID: I do remember sort of waking up. Even if I wasn't really asleep, it was nighttime. So we were sort of in a daze and got out of the bus. It was like, ‘Wow! If this isn’t maneuvered exactly right, this bus is going over.’"

Proving himself worthy of the MacReady role, however, Kurt Russell immediately assumed control of the situation.

WAITES: "Kurt became Mac. Kurt goes, 'Okay, nobody move. Who's in the seat farthest from the door?' I said, 'I am.' He goes, 'Alright, Tommy — get on your hands and knees and crawl to the front.' Slowly, I did it [and] got off the bus. One at a time, he got us all off the bus. Then the weight shifted, we got behind the bus, pushed it back on [the road], and drove [on] safely ... We arrived at 5:30 a.m. as the sun was coming up and there was John Carpenter at the bus stop, waiting for his men. He shook each one of our hands as we got off the bus, not knowing the peril we had just been through."

WEISSER: "Kurt has that quality. He’s sort of a natural leader. That’s his nature."

MALONEY: "Kurt Russell was our captain. He was hilarious and with us all the time. There was no separation of him and us the way there sometimes is with the star of a movie and the rest of the cast. We seemed to be all equals, except in the billing. At the end, of course, Kurt gets his [name] separately because he is the star."

Despite having worked with Carpenter on Elvis and Escape From New York, Russell was not immediately cast as the lead. In fact, he was the very last actor to join the ensemble. Cohen reveals that the studio suggested a young Kevin Kline for MacReady "late in the game" and Carpenter went so far as to meet with the up-and-comer at the now-defunct Tail 'O The Cock restaurant. "Our go-to watering hole," Cohen adds.

In another instance, life imitated art with a bit of dissent amongst the ranks when Carpenter decided to cut a short exchange between Windows and Palmer. "It was sort of like a build-up to us fighting. But let's say it was three-quarters of a page of dialogue. That's a lot of lines for an actor trying to get work," WAITES adds. "He and Clennon had already gone over the scene together when it was suddenly axed. The two weren't very happy about this and spent the next 10 minutes or so verbally abusing their director — completely unaware that they were mic'd up. "John sticks his head around the corner [and] he goes, 'Hey, guys, I just heard every word you said.' And he wasn't laughing. It took me a while to dig myself out of that one. We were both mortified. And Clennon's like, 'Oh, come on, John! A little mutiny is perfectly normal on every set!' I think I wrote him a note to apologize, but I felt so terrible."

Clennon remembers the moment a little differently. According to him, the altercation was not over cut dialogue, but over the efficacy of trying to reinforce the outpost doors with two-by-fours shortly before MacReady — left for dead by Nauls — forces his way inside and threatens to blow up the whole complex.

CLENNON: "I said, ‘This would never work. This is this is silly. This is bullish**.’ And what I meant was, in engineering terms, this ain’t gonna work. Any carpenter’s apprentice could tell you that what you're doing with these two-by-fours is not going to secure these doors. It's silly. John had his headphones on and my mic was on. John came tearing across the set and started screaming at me, 'It is not bullsh**!’ He was just furious with me and I was I was kind of taken aback. I was shocked that I had been overheard and he didn't persuade me that I was wrong. But I figured, ‘Okay, well, we'll just try to fake it here and maybe nobody will notice.’ I think that was the case, I don't think anybody noticed that what we were doing was, at best, a fanciful way of preventing the monster from coming through the doors."

With that said, Clennon does touch on a number of early character moments that he wishes hadn't ended up on the cutting room floor. He points to the critical and box office success of Ridley Scott's Alien, which opened three years before The Thing, and followed a similar narrative about a collection of blue-collar workers battling a seemingly unstoppable beast from outer space.

CLENNON: "One of the things that made it work for me, is that I got to know every single one of those characters. So when they were threatened, I knew who they were and I had a set of feelings about them. I thought that Bill succeeded in doing that. It was there on the page and it was there when we shot the film. When the film was released and I saw it for the first time, I thought that John had cut too much of the introductory material for each individual character ... I got lucky because he didn't cut a significant amount of my material. So by the eighth minute into the picture, you know who Palmer is. He’s an oddball, he's funny, he’s silly, and you kind of like him. You don't want him to be absorbed by Thing."

The actor goes on to claim one of the assistant editors gave him a heads up about this prior to the film's theatrical release. "She kind of warned me that John wanted to get to the first manifestation of the monster as quickly as he could. And so, he dispensed with a lot of the character stuff because he wanted to wow people with the monster. He was impatient, he was in a hurry to get there and he didn't want to linger over establishing a character."

"You Gotta Be F***ing Kidding..."

We'd be remiss if we didn't talk about the most iconic scene in the film: the big reveal that Norris (Charles Hallahan) has been assimilated. In fact, Carpenter's favorite alien design is the Norris head that splits away from the man's body (like a TGI Friday's patron pulling apart a fresh mozzarella stick) during the iconic defibrillator sequence with Dr. Copper (Richard Dysart).

CARPENTER: "The most fun was the head coming off, sprouting legs, and crawling away. It was ridiculous, that's why. At this point, the creature was designed after the script [was written]. I read Bill Lancaster's description of this scene and he came up with the line, 'You gotta be f***ing kidding,' which I just think is perfect."

FRANCO: "Charlie was laying in this bed, kind of at a 45-degree angle. His head’s back, so his whole body is, of course, a makeup effect. He was there for like two or three hours, just waiting for everything to happen. And when it does happen, you go, ‘Oh my God! We pulled that off!’ ... We did it all in one with multiple cameras because once that thing broke, it was gonna be forever to do it again. It was one of those things where everybody was applauding."

WAITES: "[My favorite scene] definitely has to be when Dick Dysart gets his his arms bitten off. No one ever expected that. The camera's underneath, from the patient's point-of-view, and he reaches in to see what's in there and he comes out with no arms. They got a real double amputee to play [Dysart in the wide shot]. I gasped."

CUNDEY: "That had been storyboarded and when I do a film class, I show the storyboards as drawn and the actual images we shot. It's surprising how much they coordinate exactly. Because the storyboards were drawn very carefully to say, ‘Okay, here's the moment, here's the action we want to see, here’s the specific dramatic thing.’ I think the fact that it was so carefully conceived was a big help. Having these storyboards and drawings of moments also gave Rob the inspiration to say, ‘Okay, the head has to stretch like this, and it has to crawl like this.’ And rather than just building stuff, he fitted all of the stuff into the moments that had been been conceived."

BABASIN: "Every time we shot something like that, everybody grabbed something. We were all controlling some aspect of some creature. The duct monster [for example], there was a guy in the duct because that was a hand puppet. He's inside there, controlling this guy while the crew is down below with fire extinguishers. Some of us are doing fire control, some of us are actually initiating the sequence of events. Everything is done so methodically."

MacReady torches the Norris-Thing laid out on the operating table, but misses the head, which breaks away from the body and attempts to crawl off. Palmer catches sight of the arachnoid noggin and utters the piece of dialogue that perfectly sums up The Thing: "You gotta be f***ing kidding." It's a line that has echoed across generations and inspired contemporary filmmakers like Andy Muschietti, who included little homage to Norris's scuttling head in IT: Chapter Two.

CLENNON: "At some point, I think they came to the conclusion that this gag was going to be so spectacular — almost operatic. The ultimate Fourth of July fireworks display. It was gonna be so outrageous. The ideas that Rob Bottin was bringing to the table were just fantastic, and outrageous and unbelievable. I guess John and Bill came to the conclusion that the audience was going to be so blown away by this and they might even doubt what they had seen. There had to be some acknowledgement on the screen that what [the audience] had just seen was truly outrageous and spectacular. And somehow, they came up with, with that line. Maybe John or Bill just blurted it out ... It’s like a humorous affirmation of what the audience is already thinking and feeling. And if they suspend their disbelief and buy the effects, it is truly horrifying. But it is also outlandish and outrageous and pushing the limits of credibility in a very realistic way. And so, you’re giving voice to what the audience is thinking. I think that's why that line is such a classic."

DAVID: "That was some funny sh** … Clennon, he was just funny as hell."

MASUR: "The first time I saw it, I just laughed my ass of. I thought it was so great."

HOWARTH: "It’s so iconic. You could say that it’s derivative of Alien with the thing popping out of the guy, but this was on 10x. It was just so much more unexpected ... the gooey thing coming off the table and sprouting legs. It’s a holy f*** moment."

When we ask BRYAN what he remembers from that day, he replies: "Just that the flamethrowers were really hot."

"Now I'll Show You What I Already Know"

For the infamous and tension-filled blood test sequence, CUNDEY devised an ingenious system for hinting at the identity of the imposter: "I took a certain liberty that when the guy we're most suspicious of is seen, I didn't put the eye light in his eyes. I didn't put that little sparkle that we use most of the time on characters to create the sense of life, of intelligence. I kept the light out of his eyes, so his eyes were dark and dead. I think, just subconsciously, the audience sensed that. It wasn't until years later that I said, ‘Okay, well, let me tell you what I did.’ And people said, ‘Oh yeah, now I notice.’ But it wasn't so much noticing as feeling, sensing, adding to the suspense. I think it paid off because it built that suspense as we went down the line from character-to-character and he was always lurking and waiting."

BRYAN: "Everybody has an eye-light, except David [Clennon]. And it was discussed at the time, ‘We don't want to put an eye -light there because he's not human and it'll be so subtle that people really won't pick up on it' ... I've always thought that was a really clever way to psychologically telegraph to the audience that there's something wrong here."

To achieve the effect of Palmer's blood running away after it's been touched by the hot wire, the crew built a custom section of flooring attached to a gimbal that could move in any direction. "Then we attached the camera to the floor, so it stayed stationary, looking at this floor," CUNDEY explains. "No matter what direction we we moved the floor, the camera was always looking at the same spot. And then we put the blood on the floor and moved it around. As it would run in a particular direction, the camera would only see it as crossing the frame. I think it was pretty effective."

FRANCO: "Today, it would just be, ‘Okay, we’re just gonna have the petri dish there. Okay, rolling…cut!’ And then later here comes the blood and the Thing [via CGI]. It would probably be way more spectacular and more stupid. It wouldn't make any sense, but it would be a bigger jolt. Also, John was a master of of musical stingers. It'd be very quiet and something would go off and there would be this big, loud, musical note or something that would blow you right out of the chair. He knew how to do those things. It's brilliant filmmaking."

DAVID: "I remember watching the behind-the-scenes process that you do to make the film moment work. Where the blood was being pumped from and how it was going to look. The most remarkable thing was the hand and the petri dish. The hand is a mold of Kurt's hand, but it wasn't his [actual] hand."

CLENNON: "When you stick a needle in a human body, graphically in close-up, the audience is going to have reaction. When you cut somebody's thumb with a scalpel, I'm going to have a major [visceral] reaction … So my theory is that a horror film director can use needles and scalpels and fake blood to make an audience anxious and apprehensive and vulnerable to what's going to happen next ... having been softened up and made apprehensive and anxious and vulnerable, the effect of what you show them next — which is not real — is is going to enhance the effectiveness of the gag that you're springing on them."

Once exposed, Palmer starts to transform and ends up attacking poor Windows, who fails to burn the creature in time. "I believe I did my own stunts [for that]," WAITES says. "They put me on some machine [and] that's me shaking around. I think I did a few takes of it and then they said, 'Okay, let's do it with the stunt guy.' I seem to remember John letting me do it because I was in quite good physical shape at that time."

CLENNON: "I think maybe there were two or three grips, perhaps, just out of frame, who were shaking the sofa. I don't know if I was trying to amplify the shaking myself, I don't remember," Clennon says of Palmer's horrific convulsions just before the man's head splits open. "What strikes me about that scene, is that my face is expressionless. There's nothing going on with my face. I'm not grimacing or mugging for the camera. That’s a good thing, I think it's kind of striking that it's almost like Palmer’s not there anymore, it’s just his body vibrating as the Thing emerges. It’s almost like he's a corpse ... That's a very effective moment that the editors found and used to good effect."

For Clennon, the sequence works so well because Carpenter and Lancaster chose "the most unlikely character to be the Thing ... he is the least likely candidate. It can’t be Palmer, he's too flaky, he's silly, he's harmless, and he's funny. The Thing is not going to inhabit him! It's just not right. And lo and behold, that’s what you get ... I don't think anybody's ready for it to be Palmer. There’s nothing sinister about Palmer and then all of a sudden, [it turns out] he fooled you."

According to BABASIN, Palmer's transformation was also set to include slime oozing out a pair of fake arms "that had like a thousand pinholes in them and there was a pipe down each arm that pumped in K-Y Jelly. The K-Y was supposed to ooze out of all these individual holes and look really creepy. They needed someone who had a similar body as Palmer at Hartland, so they came running up to me. ‘Hey, you want to sit in for Palmer?!’ I was like, ‘Yeah, sure!’ So I sat on the famous couch, had my arms back, and had these fake arms come out. I guess the visual just didn't look good. It was another one of those trial and error things. I think as the ooze came out, it would just become one mass [of] ooze. It didn't have those individual little squiggles, which I think they were looking for from each one of those little pinholes. So that was axed."

The scene ends with one of the biggest laughs in the movie. Still tied up, a weary and beleaguered Garry explodes at his comrades: "I know you gentlemen have been through a lot, but when you find the time, I'd rather not spend the rest of this winter TIED TO THIS F—ING COUCH!"

WAITES: "We burst into laughter, it was really hard to keep it in. John's sets are really fun."

"Yeah, Well F*** You, Too!"

In addition to the UFO model that opens the movie, FRANK also found herself tasked with creating a miniature version of the outpost generator room for the movie's explosive climax. “I went over and measured everything, took a big chunk of foam, cut it out, and figured out how to do all the different cans and that stuff."

The effect of the alien destroying the floor was achieved with what BABASIN calls "the tortoise shell," a battering-ram like device that moved along and track, forcing "this hard, fiberglass tortoise shell through the floorboards. That was a very elaborate mechanical effect."

That same artifice was applied to the scene where MacReady lobs Molotov cocktails into each room out of the outpost in an effort to deprive the alien from any sense of shelter. "We we had to rig gas mortars up in each individual room," says BABASIN. "And as he walks down the line, lighting fake Molotov cocktails and throwing them in, we're blowing the heck out of the set. That's all interior. So you'll see an interior blow up and then they'll go [to an exterior shot] of British Columbia and you'll see a big bomb go off. Then you'll go back inside and you'll throw a couple more Molotov cocktails. It's all edited together, obviously, and it looks quite impressive when it's done."

MacReady’s final standoff with the Blair-Thing was originally supposed to feature an extensive amount of stop-motion work by Randy Cook — only a fraction of which made it into the finished cut. “It was some great stuff," CARPENTER says. "The creature comes up out of the floorboards and you see these tentacles. The problem is that everything we'd done was live-action [and] it just didn't fit. It just looked like a different movie and that was troublesome. So we just used the bare minimum.”

BABASIN: "I know there's a picture out there of the miniature that Randy Cook did. It's got the dog creature [and] he's grown out and away from the original Blair monster. I have to say, it almost looked too good. It was so meticulously done and the creature in the movie, they never really developed him that way. The dog came out, but he didn't grow across the entire compound like it appears in the miniature. The miniature looked great, but I just don't think it really meshed well, continuity-wise, with the the full-size creature."

CUNDEY: “Stop-motion at the time was still very stuttery and so, they decided to eliminate what had been designed in the storyboards and keep it down to one shot."

The Thing's ultimate form — an amalgam of man dog, and cosmic horrors beyond our feeble comprehension — was a Bottin-created puppet. "I remember there were over 40 guys on the final [Blair] monster. We were all just crammed underneath," BABASIN remembers. "This thing was built on a stanchion that was six feet off the ground. There were like 40 guys underneath it, all of them controlling something and bringing the dog forward and, oh my gosh, it was insane."

COHEN: "We were running out of money. Rob's shop was like a boulder rolling downhill, picking up labor costs. John had to go hat in hand to Universal for the last $100,000 in order to make the monster, otherwise there wasn't going to be one. A lot of it didn't work quite the way we wanted it to. Nauls was supposed to pop out of it, the dog was supposed to move much faster. There were a lot of things going on that we couldn’t do."

Since Cundey had to move on to another project (most likely Halloween III: Season of the Witch), BRYAN was tasked with overseeing a number of special effects shots, which included the Blair-Thing. "I went in and shot about two weeks of the rubber work that Rob was doing," says the first assistant cameraman. "I got to do the Blair Monster at the end with the dog coming out of it, Clennon’s head breaking apart and becoming jaws [during the blood test scene], and several other things."

Indeed, a lot of supplemental material was shot once filming had already wrapped on the main actors as FRANCO reveals: "I played every single one of those characters in some kind of insert. We’d do a hand opening a drawer to get something out and I had the outfit of the person. Or we’re going over the shoulder on to this mechanical effect and I’d be the shoulder. It was just a few of us [shooting] the isolated stuff with the mechanical effects and [everything that wasn't] tied to actors or the big set. Just little two-walled sets and things like that. There were only 10 or 12 of us around doing those kinds of things. Rob had his army, but the filming company was just the camera and a couple of crew members."

BRYAN: "There were a couple of times when we were on the clock for more than 24 hours because something went wrong with one of the effects and it had to be redone, which meant that they had to be re-sculpted and the rubber had to be done. Instead of going home and coming back another day at that point, we were really up against the gun. John knew exactly what shots he needed and as we would finish them, they would literally go to the lab, send them to the editors, and cut them into the picture. There was a few times when there would be an eight-hour break or a nine-hour break in between one take of something and the second take."

Multiple cameras were used to capture the total destruction of the camp once MacReady lobs the stick of dynamite at the Blair-Thing. "They blew up the set, which was gorgeous at night," POLIS recalls.

FRANCO: "The whole inside of that thing was scored with chainsaws ... Everything that was holding it together was cut almost right to the bone, so that when the bombs did go off it, it really did explode."