Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

So Earth might have once had a cousin, and it left behind a piece of itself

While everything else was burning up in the garbage inferno that was 2020, a lone meteorite fell to Earth in the Sahara Desert. Gasps would ensue when scientists found out what this unassuming piece of rock really was.

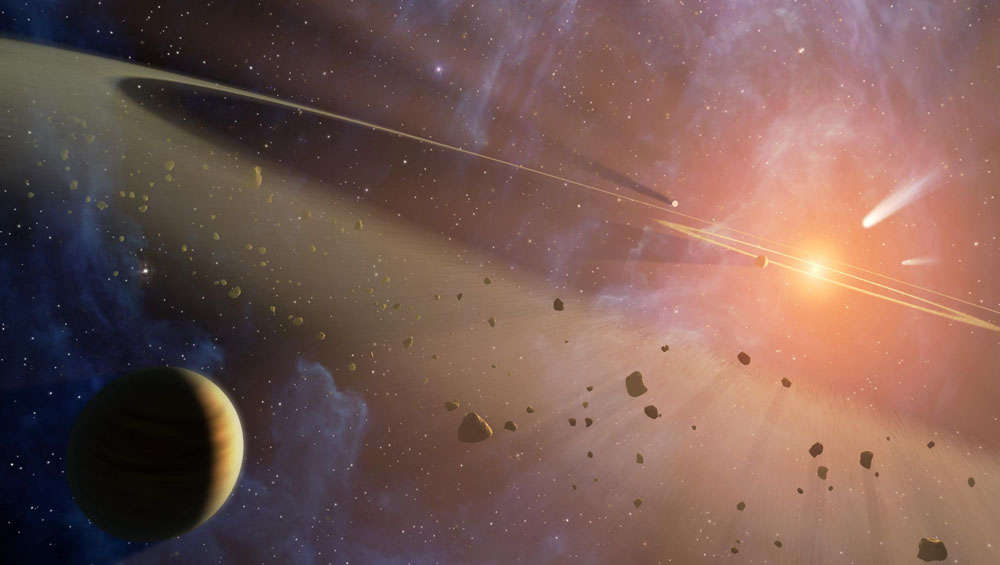

Even older than Earth, the fragments of a 4.6 billion-year-old meteorite otherwise known as Erg Chech 002 (EC 002) are actually the oldest specimens of space magma (which has obviously long since cooled off and solidified) ever found. Now scientists believe it might also be a relic of a protoplanet that could have been our planet’s long-lost cousin. Whatever primordial planet it came from must have been smashed to pieces or long since accreted into a rocky planet that was forming back then.

Besides possibly being a cosmic relative, EC 002 has a strange mineral composition that has never been seen in any asteroid or meteorite, even after being compared to more than 10,000 of them. It may reveal more about how the oldest planets in the universe formed.

“The formation and nature of the primordial crust generated during the early stages of melting is poorly understood, due in part to the scarcity of available samples,” said the team of scientists who peered into the past through EC 002 and recently published a study in PNAS.

What makes this meteorite such a find is that it is made of andesite. Most protoplanetary crusts are thought to have been made of this volcanic rock, which is also found on Earth. Andesite is coarse-grained and usually ranges from a light to dark gray flecked with greenish crystals. It is rich in silica and feldspar, while basalt is much darker, fine-grained and made mostly of iron and magnesium. Basaltic crusts were rare almost 5 billion years ago.

EC 002 is achondritic — missing the tiny spherical grains, or chondrules, embedded in most meteorites. It probably formed from partly molten magma on a larger chondritic asteroid. The amount of aluminum and magnesium isotopes observed by the team seem to suggest that it EC 002 started out as a blob of thick magma that took several hundred thousand years to harden. Objects like it might have broken off larger bodies from a collision or failed to stick to a developing young planet.

“Protoplanets covered by andesitic crusts were probably frequent. However, no asteroid shares the spectral features of EC 002, indicating that almost all of these bodies have disappeared, either because they went on to form the building blocks of larger bodies or planets or were simply destroyed,” the scientists said.

You can find out at least some of a meteorite’s chemical composition by aiming a laser at it. Reactions depend on what kind of light is being aimed at the rock. Short wavelengths of invisible light, like UV light, will be absorbed and then emitted as visible light. Long wavelengths like infrared will do the opposite, with the mineral absorbing visible light and emitting invisible light. Andesite is high in feldspar, which can be identified with an infrared laser beam.

Finding out the age of iron meteorites has shown that the earliest planets most likely formed during the nascent solar system’s first few million years of existence. At the dawn of the solar system, protoplanets had such different chemical compositions because decay of an aluminum isotope gave off massive amounts of heat, which melted an ocean of magma. The surface of that ocean would cool into andesite similar to EC 002.

We may never know what happened to the rest of the body EC 002 came from and whether it really formed close to, or even broke off from, Earth. Maybe the rest of it is hiding deep underground somewhere.