Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

How about 10% of the oil from Deepwater Horizon oil spill was eaten by the Sun

It's almost like it's burning the oil away, just really slowly.

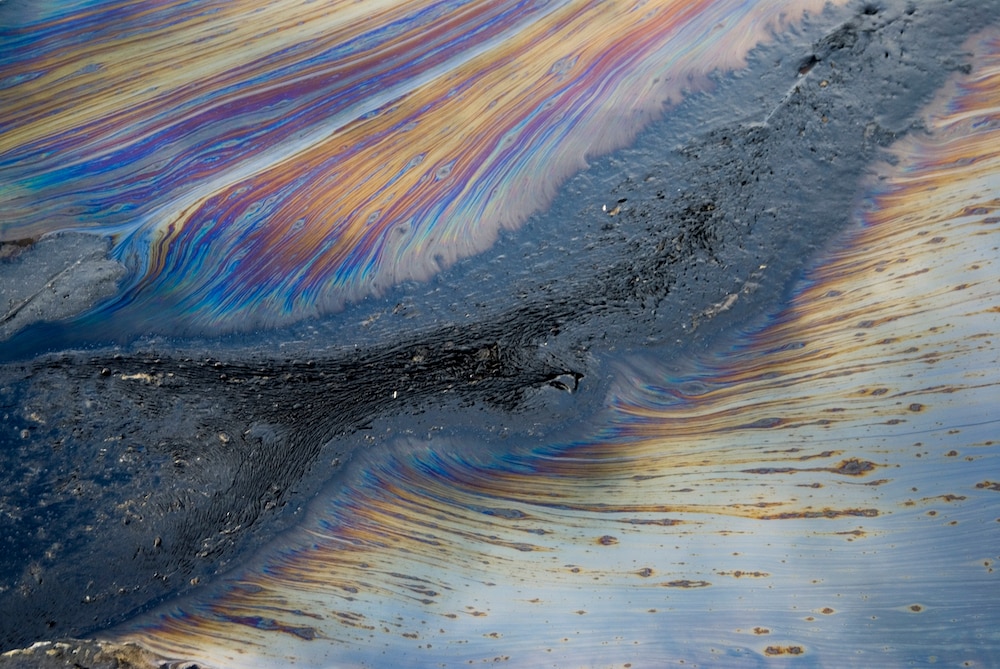

The Exxon Valdez oil spill was such a significant environmental event that its name has become synonymous with disaster. More recently, the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico introduced approximately 210 million gallons of crude oil into the environment.

These events result in considerable environmental harm and the efforts to clean them up can last years. Even then, it’s impossible to recover all of the oil which has been released. Interactions with the environment move the oil around in ways we don’t fully understand. Scientists expend considerable effort trying to understand where all that oil goes, a concept known as environmental fate, in an effort to understand the longstanding impacts of environmental disasters.

There are a number of common fates for unrecovered crude oil. Some of it is likely consumed by microorganisms, some of it evaporates into the air, and some of it ultimately finds its way to the shoreline where it is mixed in with the soil. Still, more often than not, we end up with a portion unaccounted for, a percentage of oil spills which vanishes into the environment we know not where.

A recent study carried out by Collin Ward and Danielle Haas Freeman from the Department of Marine Chemistry and Geochemistry at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute has closed some of the knowledge gap by reconciling interactions between surface oil and sunlight. Their findings were published in the journal Science Advances.

“Typically, oil and water do not mix, but the light energy absorbed by oil initiates a series of reactions that add oxygen to the compounds in oil,” Ward told SYFY WIRE. “The transformation products are more soluble and can dissolve into seawater.”

In essence, when sea surface oil absorbs sunlight, it generates reactive oxygen. That oxygen can then oxidize oil deeper down which doesn’t come into direct contact with sunlight. The process transforms oil into new compounds which can dissolve into sea water.

Precisely how much oil is converted through this process isn’t wholly clear, as the process happens largely outside of our ability to observe it directly. The quantity of converted oil is also dependent on a number of factors including the thickness of the surface oil, distribution over the water, as well as the time of year and global location. Oil spills at arctic latitudes or during winter months necessarily receive lower solar exposure and thus are less impacted by this process.

In order to estimate the impact of sunlight on the environmental fate of oil spills, scientists developed experiments using LEDs with variable wavelengths by which they could simulate sunlight-oil interactions under different conditions to see how much of it dissolves into the water.

“In total, hundreds of thousands of data points led to our estimate that nearly 10 percent of the floating oil in the Gulf of Mexico dissolved into seawater after sunlight exposure,” Ward said.

These findings are good news for cleanup efforts as they mitigate the amount of oil that must be burned or otherwise collected. On the other hand, it’s unclear what the downstream impact of dissolved oil is on the larger ecosystem. It’s possible that some or all of the products of these chemical interactions are detrimental to the plants and animals who live in marine ecosystems.

“The net balance of the potential impacts of photo-dissolution on ecosystem health remains an open question that should be explored,” Ward said.

There’s something satisfying about at least knowing where the oil ends up. Understanding that allows us to better explore the long-term impact of oil spills and, potentially, mitigate the negative consequences. Like a monster encountered in a dark forest, it’s best to at least be able to see the treat, in order that we might have a better chance at attacking it head on.

Preventing and addressing oil spills will continue to be a priority so long as our societies depend on fossil fuels. We need better systems for ensuring the risk to global ecosystems is limited as much as possible and more robust knowledge about what happens when things go wrong. In order to do that, we need to be able to bring the whole process out into the sun.