Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

The First Spark of Life on Earth May Have Come from the Sun

Even early life preferred sunny days over stormy ones.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein remains one of the most influential and definitive pieces of science fiction, more than two centuries after it was first published. The Monster has appeared in more than 75 movie or television productions, including Universal’s 1931 feature film Frankenstein, the 1948 comedy starring Bud Abbot and Lou Costello, and a 2015 adaptation starring Xavier Samuel and Carrie-Anne Moss (now streaming on Peacock!) which reimagines Frankenstein in a modern context by trading graveyard butchery for genetic engineering.

In Shelley’s story, Victor Frankenstein endeavors to create life from scratch, using the biological building blocks (stolen corpses) available around him. But the pieces, having been assembled, remain inanimate until acted upon by a bolt of lightning. While much of Shelley’s tale remains blessedly impossible, she was onto something with that lightning strike.

REPLICATING DR. FRANKESTEIN IN THE LAB

In 1952, Stanley Miller and Harold Urey, both at the University of Chicago, conducted a now-famous experiment replicating the conditions of the early Earth. They simulated the atmosphere of the early Earth by filling a glass vessel with methane, water, ammonia, and hydrogen. It has since been determined that their chemical mixture may not accurately represent the early Earth, but we’ll let that slide for the moment.

RELATED: Life’s Peptide Building Blocks Could Have Originated In Space

Miller and Urey connected their vessel of “primordial soup” to another vessel half-filled with water and exposed to a heat source. The water vessel boiled, generating water vapor which was allowed to travel to the soup container. Lastly, but perhaps most importantly, Miller and Urey applied an electrical spark to the flask, which traveled through the water vapor and chemical soup, simulating lightning strikes hitting the Earth’s early atmosphere. The system was then allowed to cool so that the vapor condensed on the sides of the vessel where they dripped into a collection chamber at the bottom.

When Miller and Urey looked at the contents they had collected, they found half of the 22 amino acids which appear in DNA. They concluded that if you put the right ingredients under the right conditions, the building blocks of life will emerge, for lack of a better term, organically. Over the intervening decades, scientists all over the world have replicated and refined the experiments. We now know that the initial experiment likely had an incorrect chemical mixture and didn’t account for mineral contaminants from the vessel itself, but the overall premise remains sound. Ordinary chemical elements, when mixed together in the right ratios and exposed to a source of energy, will produce more complex organic chemistry.

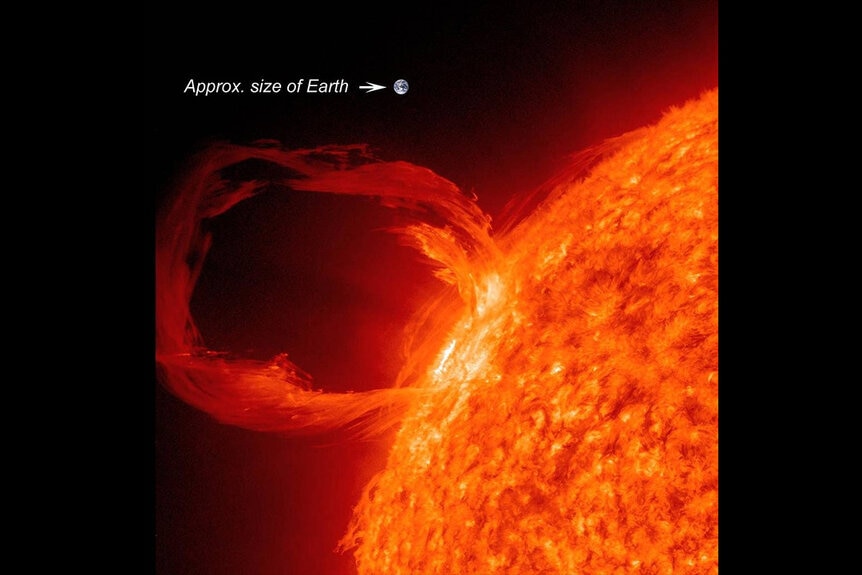

DID SOLAR FLARES HELP OR HINDER EARLY LIFE?

It’s long been believed that life emerged on Earth not because of solar activity, but in spite of it. Yes, solar energy was crucial for life, but the early Sun was overly fond of temper tantrums that might have made the early environment especially hostile. Constant bombardment by solar flares and coronal mass ejections (CMEs) might have blasted the Earth so fully that any life emerging would die in a cleansing fire. Or maybe not.

A recent study published in the journal Life suggests that those early solar outbursts were a crucial part of the recipe of life. You can put all of the ingredients of a cake together, but it’s only batter until it’s baked. The same might be true for life. A team of researchers led by Kensei Kobayashi, from the Department of Chemistry and Life Sciences at Yokohama National University, performed an updated version of the Miller-Urey experiment looking not just at lightning strikes but at a variety of energy sources.

While the original 1952 experiment attempted to replicate the conditions of the early Earth, the new experiment looked further afield to build a larger picture of how the solar system and even the galaxy might have impacted the emergence of life. Researchers conducted a number of “life in a bottle” experiments, simulating the impact of lightning strikes, UV radiation, galactic cosmic rays (GCRs), and solar energetic particles (SEPs), themselves the result of super flares during the Sun’s adolescence.

They then examined how much and how many types of organic molecules emerged from their artificial atmospheres. Researchers confirmed what Miller and Urey demonstrated more than 60 years ago: Lightning strikes will produce organic molecules. But it isn’t the most efficient way. Not by a long shot. Rather than constrain the production of organic molecules, like scientists long believed, SEPs generated even more amino acids and carboxylic acids than other methods. GCRs took second place, with lightning strikes trailing in third place, and UV radiation producing almost nothing.

According to scientists, SEPs generated by the young Sun appear to be the most effective energy source for forming prebiotic compounds. And given the overactive nature of the early Sun, there would have been a lot of SEPs cranking out amino acids like it’s their job.

In retrospect, Dr. Frankenstein could have avoided the gloomy castle and the pouring rain altogether if he’d just taken his creation outside on a sunny summer afternoon. Admittedly, it’s not quite as cinematic.

Catch Frankenstein, starring Xavier Samuel and Carrie-Anne Moss, streaming now on Peacock!