Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

The star cluster that wasn't: How did M73 fool generations of astronomers?

I love a good coincidence, and this story has two. One is pedestrian, the other cosmic.

It starts with me pondering Gaia data. Gaia is a European Space Agency observatory that is revolutionizing astronomy. Its mission is to accurately map the positions, colors, distances, and motions of over a billion stars — yes, a billion, about 1% of all the stars in our galaxy — and create a massive database of the results, essentially a 3D map of the Milky Way galaxy.

Such surveys are incredibly useful. New objects can be found this way, like stellar streams. Sometimes hidden objects reveal themselves in the data. The shape of the galaxy can be found, as well as the distances to star clusters, the remains of cannibalized galaxies, and, importantly, the distances to some stars that are used to calibrate our distance scales to other galaxies, and from there the Universe.

And, sometimes, they can solve age-old mysteries. For example, the star Albireo is a close double star, but are the two stars physically related? Astronomers argued for a long time, but Gaia data easily showed that nope, they're not related, at two very different distances but just coincidentally aligned in the sky.

Which brings us to M73.

This is purportedly a small, loose cluster of stars in the constellation of Aquarius. The M in its name means it was catalogued by the famous French astronomer Charles Messier, who was a comet hunter in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. As he scanned the sky looking for these objects, he kept stumbling on fuzzy things that were easily mistaken for comets, and he got irritated enough by them that he listed them in his now-famous Messier Catalog, so that others might not be fooled.

Thing is, those are some of the brightest and best-known objects in the sky now. The Orion Nebula, the Andromeda galaxy, the Pleiades... all of these and 100 more sport M numbers.

And then there's M73. This is the object in question:

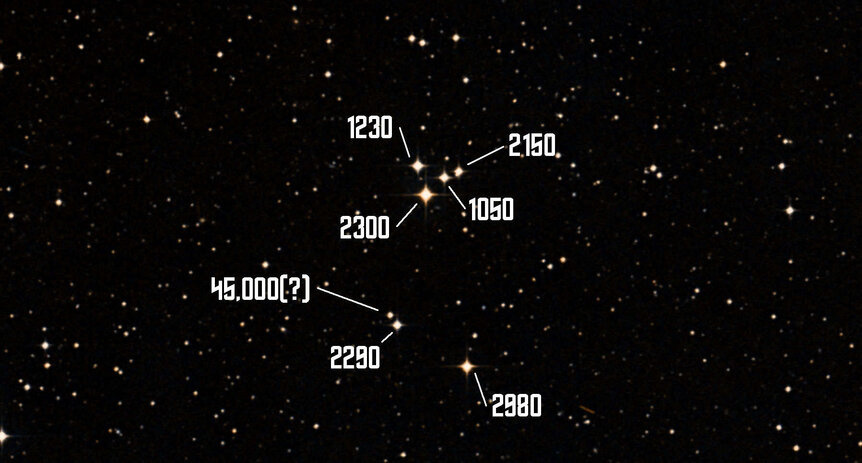

I know, right? Not much there. The cluster is composed of the four bright stars in the center, and the three slightly dimmer ones below. To Messier, in his small telescope, they looked a bit fuzzy so he listed them, claiming he saw nebulosity around them, what we now think of as clouds of gas and dust. Many clusters are still embedded in the material they were born from (see the aforementioned Pleiades), so fair enough.

Decades later, John Herschel was making his own, much larger catalog, called the General Catalogue of Nebulae and Clusters of Stars, and noted that M73 was listed by Messier. To him they just looked like stars (he notes it looks "very poor" and lists it as "Cl??" meaning "cluster??"). Years later, when John Lewis Emil Dreyer compiled the extensive (and still used) New General Catalog, he listed M73 in his catalog as NGC 6994, and while he copied Herschel's comments he took the question marks away, so it's listed as just "Cl, eP, vlC, no neb.": cluster, extremely poor, very little compressed, no nebulosity"*.

And that's the thing. Ever since then — over a century ago! — astronomers have argued over this collection of 7 stars. Is it a cluster or not?

It's a fair question. Clusters usually have dozens or hundreds of stars, but as they age stars get ejected, and at some point you're going to have just a few stars hanging out together. Is M73 one of those?

Two papers came out by professional astronomers at almost the same time tackling this issue. Although using different telescopes, they both looked at the colors of the stars — if plotted a certain way, that can be used to determine if stars belong in a cluster or not. And guess what? Go ahead, guess!

Yup. In one paper a researcher concluded the stars were not in a cluster, and in the other, they concluded they were. Hurray.

So which is it?

About a year later, another team of astronomers took spectra of the stars, breaking their light up into individual colors, in order to look for a Doppler shift which determines if the stars are moving toward or away from us, and how rapidly. If the stars are physically in a cluster, they should all have roughly the same velocities.

And... they don't. One, for example, is moving toward us at 53 kilometers per second, while another is moving away at 35 km/sec. The others are scattered all over the place in between those two values.

It's pretty clear, then, they're not in a cluster together.

But, maaaaaybe they recently underwent some big scattering event, sending them every which way. That's hugely unlikely, but it would be nice to know for sure.

... and that brings us back to Gaia. It measures the distances to stars via parallax, and is very accurate for stars like this. The conclusion?

Nope. The stars are at all different distances, ranging from about 1,000 to 3,000 light years (although one has a distance of 45,000 light years, which is far enough that Gaia has a harder time measuring parallax, so the distance is a bit uncertain). A cluster of stars is usually just a few dozen light years across at most, so these stars are clearly physically unassociated with each other.

Their apparent closeness in the sky is therefore a coincidence, an illusion. It's like seeing a bug on your window apparently next to a distant mountain. The Universe is tricksy that way.

In other words: M73 is not a cluster. Never was, never will be.

So that's the cosmic coincidence. What's the pedestrian one?

As I said, I've written about Gaia data debunking some astronomical objects like Albireo. As an amateur astronomer of many decades, I've done my share of scratching my head over M73 (though honestly I've always leaned toward it being an outcome of chance). So I've had a note to write about this for a couple of years, but just never got around to it.

Then out of the blue I got an email from reader Dean Lewis. He asked me if I had seen the Deep Sky Videos series, created by professional astronomers, that goes over (nearly) every object in Messier's catalog.

I hadn't, as it turns out, despite it being done by people like Dr. Becky Smethurst, a noted and wonderful science communicator. And amazingly — the second coincidence — the video he watched that made him want to contact me was on M73!

Well! That pushed me to finally write up this little tale. And Dr. Smethurst had some info in her video I was unaware of, and used as reference material in the article you're reading now, matter of fact. She did a great job, so give it a watch:

Lovely. I like how she talks about confirmation bias, and even how astronomers can be fooled, even when looking at almost essentially the same data. One reason we have so many rules in science when publishing is to avoid bias in our interpretation of data. It doesn't always work, but in the end here we are. We now know M73 is not a cluster, and we've learned — hopefully — to be a little more careful.

Gaia has been an amazing tool for this. And it's nowhere near finished, either. A new data release is scheduled for December 2020, and will have 1.5 billion stars in it. What new treasures are buried in the observations?

And what treasures do we hold now that it will show to be fool's gold? With open eyes and open minds, I guess we'll find out.

* Correction: I originally made some errors in this part of the article, saying William Herschel made the NGC; I conflated a couple of things there. William was John's father, and while he and his sister Caroline made a catalog, the NGC came later. My thanks to Larry Faltz, editor of Sky WAAtch, for pointing this out to me!