Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

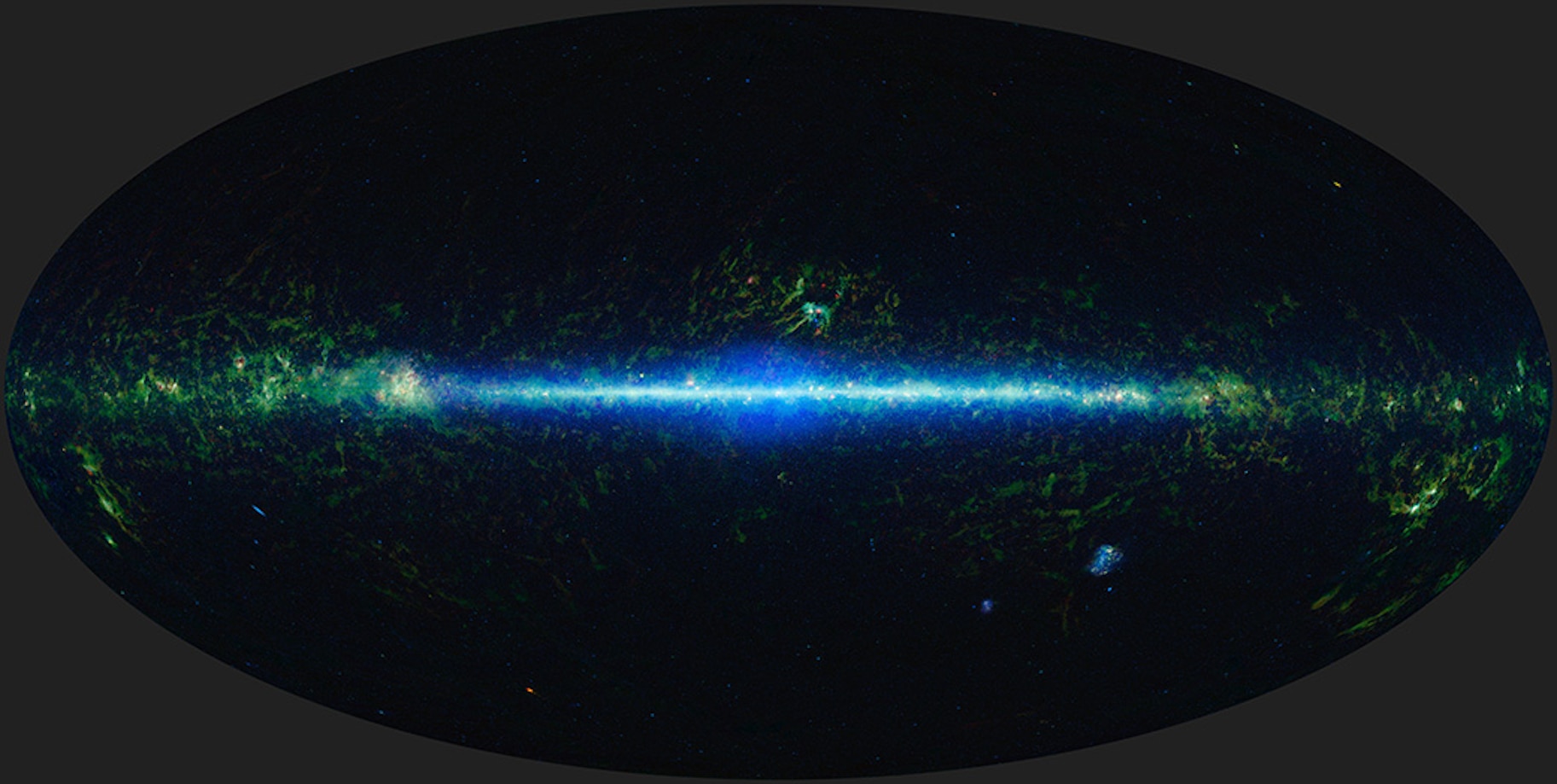

NASA captures the whole universe in illuminating decade-long timelapse

Play that again.

About Time follows the story of Tim Lake, played by Domhnall Gleeson, as he navigates his family’s unusual talent. All of the men in his family have the ability to travel backward in time and relive moments they have experienced before. Tim uses this ability in an attempt to improve his relationships, viewing his life as a movie which could be recast or reshot with the clarity of seeing a lifetime in time lapse.

Those of us in the real world don’t have the benefit of seeing our lives that way. Instead, moments pass rapidly across a comparatively static planetary tapestry. Those same challenges are present at a much larger scale in the field of astronomy, as scientists attempt to understand the immense complexity of the universe with momentary glimpses through telescopes.

Despite the incredible beauty of images from Hubble and the JWST, they are limited in what they can tell us because they see the universe in still life. Those snapshots, startling in their detail, are only brief moments within a complex set of interactions tracing back nearly 14 billion years. Often, astronomy is like watching a movie but instead of a cohesive moving picture, you get a few dozen stills out of a two hour runtime. You might be able to infer the broad strokes of what’s going on, but the story would be necessarily incomplete.

To get the full picture of what’s really happening, whether in a movie or in the universe, you need to see those stills put together to see how things move and interact with one another over time. Getting a movie of the entire cosmos is no easy endeavor, we can’t really get all of reality onto a soundstage, we can’t offer stage directions, and we can’t yell cut. There are no do overs and no second takes, but that hasn’t stopped us from trying.

NASA’s Near-Earth Object Wide Field Infrared Survey Explorer, otherwise known as NEOWISE, was initially intended as a tool for tracking distant objects outside of our solar system. It used cryogenically cooled detectors to search the skies for infrared light. Then, in 2011, the onboard coolant ran out and its initial mission ended. Some of the tools aboard the craft were still operational, however, and NASA re-tasked it with scanning the skies in all directions and keeping an eye out for movement against the background. The primary goal of this new mission is to detect near-Earth objects and provide us with an early warning of any potential impactors. It’s the sort of information which might come in handy if we ever need to send something like DART out into the void to save us from certain doom.

While doing that, the craft’s infrared telescope has continued to scan deep space as NEOWISE slowly orbits the Sun. The craft follows Earth around its orbit and takes pictures in every direction. Every six months, those slices are stitched together into a map of the entire sky. Over the last decade, NEOWISE has taken 18 of these all-sky maps, each one capturing millions of individual objects. Now, scientists have taken all 18 of those cosmic maps and stitched them together into a brief timelapse movie.

Those maps, even taken individually, provide important information for scientists studying the stars, but when taken together they reveal parts of our universe which might otherwise have been missed. In the process of its extended mission, NEOWISE has revealed the quiet motions of countless celestial objects in incredible detail.

Using only the first two all-sky maps, astronomers identified roughly 200 brown dwarf stars within just 65 lightyears from the Sun. The trick to those discoveries is the difference in apparent motion between objects which are near and objects which are farther away.

Imagine that you’re standing in a field and watching two people walk perpendicular to your point of view. One of them is 10 feet away while another is 1000 feet away. Even while they’re walking the same speed, the person closer to you appears to be crossing the distance more quickly. The same thing happens with stars.

When we look up at the night sky at any given moment, the stars appear to be mostly static. Any motion you see is most likely caused by the rotation of the Earth, not the motion of the stars themselves. When you watch the sky in time lapse though, some objects make themselves known by their rapid motion across the sky. In many cases, those objects are brown dwarfs, objects more massive than giant gas planets, but not large enough to fuse material and become a star. They don’t emit much visible light, but they do shine in infrared, which makes them perfect for an instrument like NEOWISE.

According to NASA, many brown dwarfs are nomadic, drifting across the sky alone without planetary or stellar companions. And that drifting can be seen when we view the sky in time lapse. Brown dwarfs weren’t the only things the time lapse reveals. Astronomers have also identified nearly 1,000 protostars, still in the process of being born inside star-forming nebulae. As the stars pull material into themselves, they flicker and fade in brightness. Watching them evolve over time could provide astronomers with new information about what happens in the earliest parts of a star’s life.

The universe is so vast, and its machinations so complex, that even a decade-long movie feels like the blink of an eye. But if NEOWISE, or other crafts like it, keep taking pictures and keep stitching them together, our view to the cosmos and our understanding of our place within it, will only become clearer.