Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Here's the version of James Cameron's 'Aliens' that you never saw

What started as one of the more disappointing meetings in James Cameron’s career led to him making Aliens, one of the greatest sci-fi blockbusters ever released — although even after that initial, history-making meeting, Aliens didn’t burst from the chest fully formed. It would take some time for this action-horror classic to find its family drama heart.

In 1983, Cameron met Alien producers Walter Hill and the late David Giler to talk about another project that wasn’t related to the sci-fi horror classic. They had read Cameron’s The Terminator script and wanted to find something to work on together, but, as Cameron recalled on the Aliens Blu-ray commentary, his pitch was not going very well. Cameron could tell by the producers’ facial expressions that “they didn’t like any of my ideas.”

However, Cameron instantly perked up when Hill and Giler tossed off a pitch of their own. Before Cameron left the meeting, Giler piped up with a comment that would forever change the director’s career and impact Hollywood history: “Well, we do have this other thing… Alien II.”

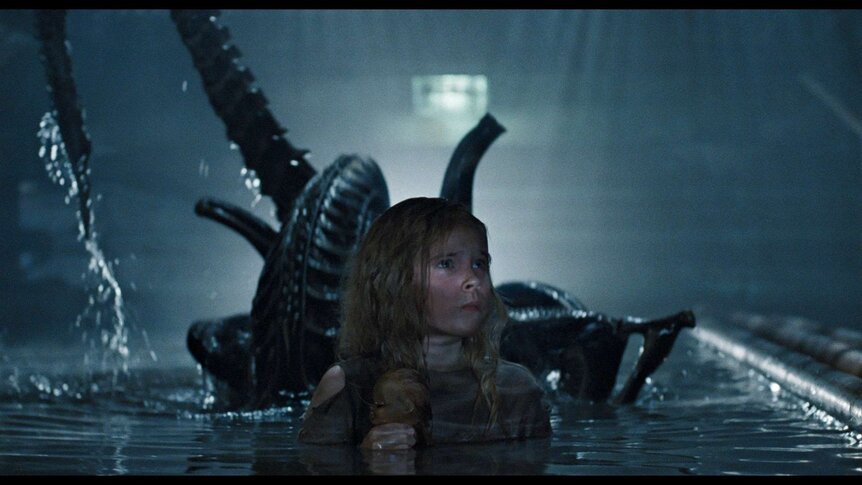

After three long days and eight pots of coffee, Cameron churned out a 50-page treatment for what would become Aliens, the first action-horror hybrid of its kind, released 35 years ago this week on July 18, 1986. For more than three decades, Aliens has reigned as one of the best sequels ever made, thanks in large part to the way Cameron wraps the thrilling and scary roller coaster ride around a surprisingly heartfelt and moving family drama centered on Ellen Ripley (Sigourney Weaver), an orphaned girl, Newt (Carrie Henn), and a grizzled space marine, Hicks (Michael Biehn). The dynamic between the traumatized Ripley and Newt forms the beating heart of the film that bloody chestbursters threaten to destroy. That relationship is one of the key reasons why Aliens is so rewatchable. But, in looking back at Cameron’s original treatment, it’s surprising to see how much of that dynamic was originally missing.

While Newt is still in this early draft of the story, dated Sept. 21, 1983, the emotional journey she and Ripley share on the way to becoming surrogate mother and daughter is slightly more than threadbare. Unlike in the Aliens director’s cut — where we learn that not only has Ripley lost 57 years of her life while floating through space in cryosleep, but she has also lost a daughter — Ripley’s child is alive (albeit very old) in this treatment. But, she hates her mother and tells Ripley so via a FaceTime-like call. Ripley’s painful realization, that she would have been better off dying than surviving only to come back to a home and family that wants nothing to do with her, helps set up the void in Ripley’s life that will soon be filled by a rescue mission to LV-426.

Ripley still meets Newt on her mission to the colony, which is located on the same planet where she and her crew aboard the Nostromo first (and fatally) encountered the xenomorph in 1979’s Alien. But missing from that encounter are small, but essential, character-building moments like the one Ripley and Newt share in the med bay. In the theatrical version, confined in this cold, sterile room, Ripley’s warm maternal side shines as she cleans up Newt’s dirty face and lays with her for a nap before they are attacked by skittering facehuggers. That’s not the case in the original treatment, which also denies Ripley one of her most necessary scenes: Finding Newt on the colony herself. In the original draft, Ripley is still aboard the dropship, so it is the Marines who locate the lost and frightened girl when they sweep the colony for survivors.

From this point onwards in the treatment, while the general narrative structure largely mirrors that of the final product, many of the details and key scenes are radically different. The Marines spend a considerable time outside the “shake ‘n bake” colony’s terraforming Atmosphere Processor, on the planet’s surface, to defend the complex from would-be alien intruders. Hicks and his unit park the armored vehicle (the APC) that Ripley drives in the film outside the complex’s main entrance and use its turret guns to sweep for approaching hostiles, as opposed to confining themselves inside the complex as they do in the final film.

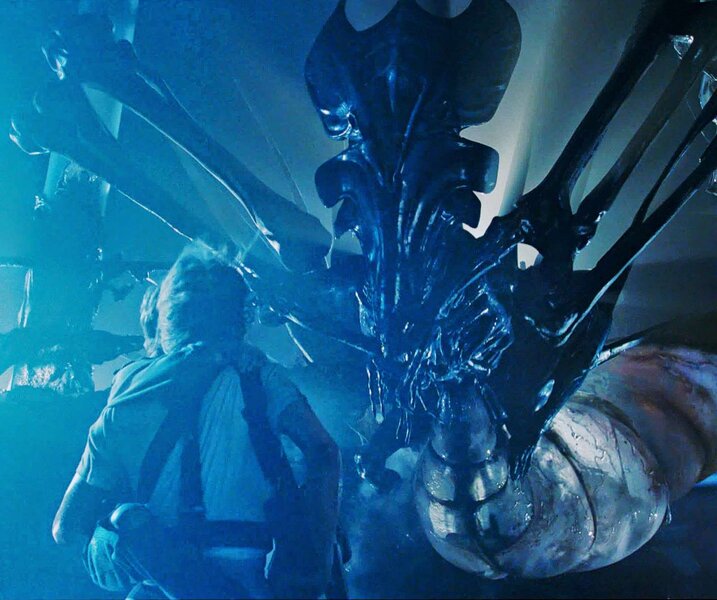

The original treatment also pushes Bishop, who is a noble and good android in the final film, in a somewhat darker direction, one that validates Ripley’s belief that his kind cannot be trusted. In the earlier version, Bishop pilots the Sulaco, not another dropship, to rescue Ripley and the others. Once Ripley arrives at the landing zone, Bishop radios her with bad news: He won’t pick her up. The risk of aliens getting off the planet is too great, and Bishop’s programming won’t let him save a few lives if it means potentially killing thousands. Ripley curses him and he departs, leaving them stranded.

The growing bond between Newt and Ripley, with Hicks becoming a father figure, is also somewhat sidelined in favor of expanding the world of the aliens and their biology. The alien drones in this version of the story have a stinger on their tails, like a scorpion’s, that can incapacitate their victims before bringing them back to the alien hive to be cocooned. With the clock ticking on when the complex threatens to explode, Ripley, Newt, and Hicks let themselves be stung by the aliens in order to be taken back to their nest, where our heroes’ only hope of escape awaits: A shuttle.

Once in the nest, the original story seems to plant the seeds for a creature we would eventually see in 1997’s Alien: Resurrection — an albino alien. Instead of the bone-white, alien-human hybrid like we saw in Resurrection, this beast is pure xenomorph — and is a carpenter of sorts (yup), with a probe that excretes a resin used to build the Hive that other aliens attempt to evacuate by removing eggs laid by the Queen. Cameron also introduces a caste of alien warrior drones; they are armed with tubules that allow them to bypass the facehugger stage and directly implant chestbursters into reluctant hosts.

One of those would-be hosts is Hudson (the late Bill Paxton), who, during an earlier incursion with the aliens, was kidnapped and taken back to the hive. It is here where Hudson dies — denied the heroic “last stand” that the final movie gives him. Instead, that sacrifice of sorts is given to Hicks. Cocooned to the hive wall and impregnated with an alien, Hicks orders Ripley to get to the ship and leave him behind. Reluctantly, Ripley goes, flies away in the shuttle, and uses the craft’s exhaust burners to incinerate the Queen’s egg chamber.

Once Ripley pilots the shuttle back to the Sulaco in orbit of LV-426, she battles and defeats the Alien Queen. Newt, for some reason, is unconscious during this epic fight. But she awakens in time to call Ripley “mommy”, just as she does in the film, before Ripley and her new child drift into cryosleep.

While Cameron’s original take had most of the key ingredients in place, it took the filmmaker and his team some time to find the right alchemy between action and character drama to make Aliens the masterpiece it is considered to be today. The process to find what the film really wanted to be involved developing the screenplay (obviously), implementing Weaver’s suggestions on the set in regards to exploring the most emotionally honest moments for her character, and fine-tuning the film in post-production. A pivotal moment in Aliens' development came after an early test screening revealed where this roller coaster ride dipped in pacing or veered off thematic course.

With the release date fast approaching, and Cameron struggling to honor Fox’s mandate to have the film clock in at 120 minutes, Aliens producer (and Cameron’s then-wife) Gale Anne Hurd made a suggestion that would save the movie: Cut the entire third reel. That reel consisted of our initial introduction to Newt and her family’s fatal encounter with the alien spacecraft home to the remains of the Space Jockey and a cargo hold full of alien eggs. (Fans have since dissected this footage with its inclusion in Cameron’s director’s cut, which was first released in 1991 on Laserdisc.) By removing that third reel, along with some redundant lines of dialogue, Hurd and Cameron discovered that Aliens works best the more it spends time with Ripley and the Marines struggling to put aside their friction-inducing differences and try to survive an ordeal that Ripley barely made it out of on her own the first time. The faster the movie put emphasis on the characters and the bond between survivors Newt and Ripley, the faster the movie could deliver its considerable emotional payload to audiences.

The action in Aliens is incredible, of course, but the film’s emotional storyline is why we still celebrate it 35 Julys since its release. Aliens is a story about what parents would do to protect their children, both human and the acid-bleeding, slimy egg-laying kind. It is also a story about family, the one you share by blood and the one that bleeds with and for you. On paper, Ripley, Newt, and Hicks — they shouldn’t work. These individuals, united by a shared trauma, shouldn’t be in the same room let alone on the same team. But, as the movie argues, is the definition of family. You find it where you can, and fight for it. And if you all lose that fight, well, then you do that together, too.

Those big emotional ideas have found their way into every film James Cameron has made. For better or worse, and with varying degrees of success, he builds his films around a love story — romantic or platonic — and tells that story using characters we laugh with but never at. Characters we can’t help but invest in for the long haul. If you take out all of Aliens’ action-packed set pieces and cool sci-fi touches — lose the Power Loader fight, Vasquez’s SmartGun, everything — what you’re left with is the reason why the film’s legacy endures: The characters.

Cameron doubles down on the emotional toll our characters endure throughout their thrilling story, the living nightmare they barely escape and come out the other side better — and more whole — than when they started. He knows that audiences can’t get this dynamic anywhere else, and that’s why Aliens still resonates long after the end credits have rolled.