Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

This Week in Genre History: Jurassic Park welcomed us all to a new era of blockbusters

Welcome to This Week in Genre History, where Tim Grierson and Will Leitch, the hosts of the Grierson & Leitch podcast, take turns looking back at the world's greatest, craziest, most infamous genre movies on the week that they were first released.

By the late 1980s, Michael Crichton was one of the most popular novelists in the world. The author of The Andromeda Strain and Sphere, he'd also made a few films, including Westworld and Coma, showing an ability to capture an audience with a killer sci-fi premise. He next wanted to write a book about dinosaurs, but he couldn't figure out the angle. "The problem always with these creatures is that once you have them, then what do you do with them?" he would say later, finally hitting on the idea that they should be part of a fantastical theme park. But although those ancient beasts fascinated him, he also had misgivings about a world in which his farfetched premise could potentially come true.

"It seems to me that we live in a society in which technology is continuously presented as wonderful," he said. "We were less exposed to the negative aspects of technology which were inevitably there. One of my interests is to provide that kind of balance to these notions that cell phones and faxes are all wonderful and great. Isn't it fabulous that we all have computers? Well, yes and no is my response."

Out of these preoccupations came his 1990 novel Jurassic Park, which imagined what would happen if cloned dinosaurs were raised on a remote island. Spoiler alert: Things don't go well.

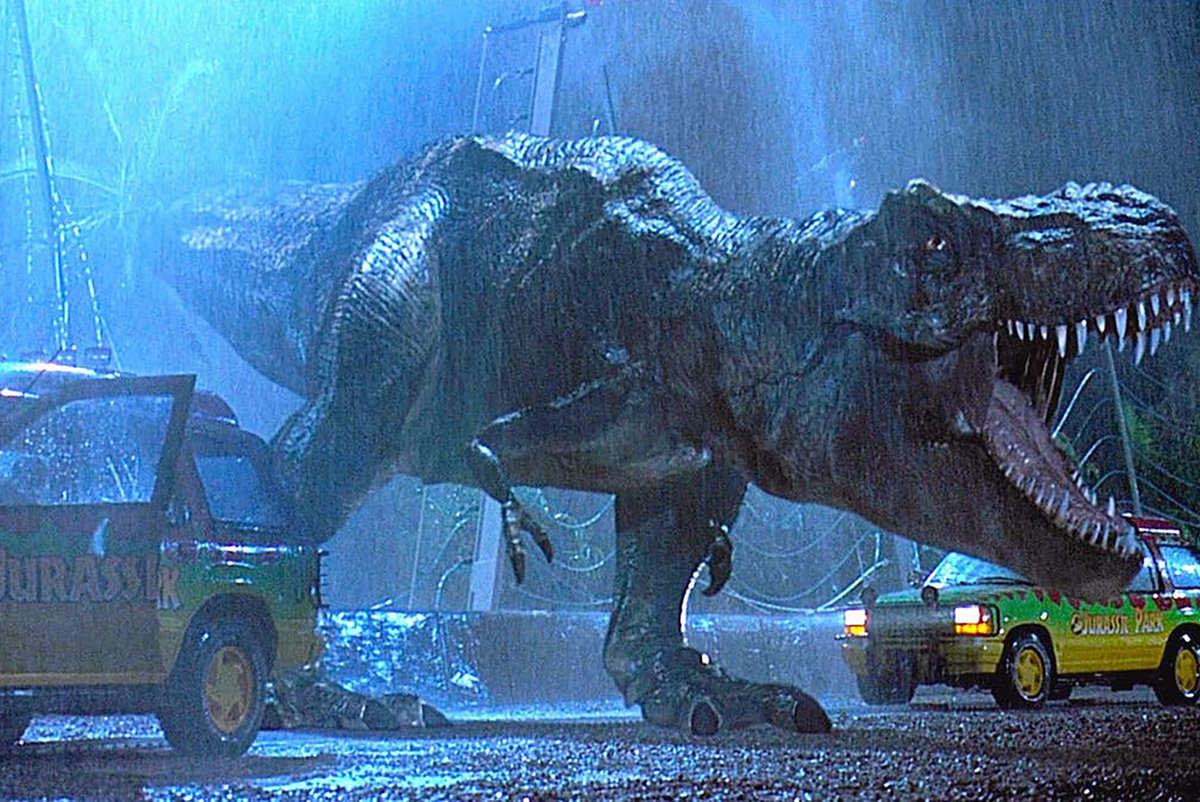

On June 11, 1993, a movie based on that book hit theaters. You could make the argument that no film in the last 30 years is more pivotal than Steven Spielberg's Jurassic Park, which is not to say it's the best or the most memorable or the greatest money-maker. But in terms of its importance in Hollywood, Jurassic Park had a brontosaurus-sized impact. The story of a group of scientists (Sam Neill, Laura Dern, Jeff Goldblum) trying not to become Jurassic lunch once the island's dinosaurs get loose was thrilling, funny, the ultimate popcorn movie. But, ironically, it was its use of technology — those very same computers that filled Crichton with such apprehension — that made the film a landmark. Special effects had been used for decades before Jurassic Park, but never quite like this, never quite so thoroughly and convincingly. "Welcome ... to Jurassic Park," Richard Attenborough's visionary entrepreneur John Hammond says famously in the movie. It was also our welcome to the CGI age.

Why was it a big deal at the time? Crichton's novel was a hit, but it wasn't necessarily a runaway blockbuster. That said, an action movie built around runaway dinosaurs was kind of a no-brainer, especially when somebody like Steven Spielberg wants to do it. After all, Jurassic Park was in his wheelhouse.

"[W]hen I read Michael Crichton's book, I flashed back to Jaws and I flashed back to Duel," Spielberg said in a 2006 interview. "Look, I'd wanted to make a dinosaur picture all my life because I was a huge fan of Ray Harryhausen." Like Crichton, he had a fascination with dinosaurs — really, who doesn't? — but he also knew that this was going to be a tricky proposition.

"The very first CGI ever used in a commercial movie was in a film that I produced and Barry Levinson directed, called Young Sherlock Holmes," Spielberg said in that same interview. "[Industrial Light and Magic] had generated a stained glass window of a knight that comes to life, jumps out of the stained glass window, and threatens our cast. That was maybe the first commercial use ever of a digital effect. Of course, the second effective use was when Jim Cameron made The Abyss and he had the water tendril and that was an extraordinary digital effect. But a digital dinosaur, a main character, had never been done before for the movies. So, in a way, Jurassic Park was the first movie where the entire success or failure of the story was dependent on these digital characters."

To be clear, the dinosaurs weren't all digital: Spielberg recruited legendary effects man Stan Winston to construct animatronic versions of the creatures. But companies would have to amp up the CGI technology in a way never seen before in a film. (The closest comparison might have been 1991's Terminator 2: Judgment Day with its shape-shifting liquid metal killing machine.) Certainly, Spielberg was at the forefront of blockbuster cinema thanks to Close Encounters of the Third Kind, E.T., and the Indiana Jones pictures, but even he had to deal with a learning curve. "My own technical proficiency is knowing how to use the yellow pages when something breaks," he told the Los Angeles Times in late 1993. "But for Jurassic Park, I practically had to take night classes so I could direct the dinosaurs. I had to learn a whole new vocabulary in computer graphic imaging."

Dreaming up what these dinosaurs would look like and how they would move consumed Spielberg's time, but when it came to casting the movie, he didn't fret over getting big stars. Sam Neill was an acclaimed Australian actor who'd dipped his toe into blockbusters with The Hunt for Red October. Jeff Goldblum had been in successful pictures, like David Cronenberg's brilliant remake of The Fly. As for Laura Dern, she had been acting since she was a kid, making a name for herself in provocative arthouse films like Blue Velvet and earning an Oscar nomination for 1991's Rambling Rose. So, Jurassic Park was a bit of a departure. "In some ways, I thought, 'I'll just go and have a good time,'" Dern said, "which, for the most part, it was. I forgot that I had to be emoting, half the time terrified, crying, screaming. You think of it as a dinosaur movie, which sounds fun."

Ultimately, the cast — which included Seinfeld's Wayne Knight and a pre-Pulp Fiction Samuel L. Jackson — was picked more for their acting ability than for their star power. This wasn't a film that needed huge names: Really, it was Spielberg and the dinosaurs that were the main attraction.

That set Jurassic Park apart from its main competition that summer: Last Action Hero, which featured the most dominant action hero on the planet, Arnold Schwarzenegger. Fresh off Terminator 2, the former bodybuilder was on a hit streak thanks to that sequel, Total Recall and two smash comedies, Twins and Kindergarten Cop. The summer of 1993 featured several potential hit films — everything from Sleepless in Seattle to In the Line of Fire to The Fugitive to The Firm — but Jurassic Park vs. Last Action Hero was the big showdown everybody wanted to see, especially because they opened a week apart in June. Who was going to come out on top?

What was the impact? Jurassic Park was No. 1 on its opening weekend, No. 1 the following weekend when Last Action Hero came out, and then No. 1 the weekend after that. It was the phenomenon of that summer, staying in the Top 5 at the box office through mid-August. It was still on more than 1,000 screens in the U.S. in late September. People simply couldn't get enough of that movie.

Jurassic Park grossed more than $900 million worldwide, a mind-boggling amount of money at that time. And it inspired a breathless piece from industry observer Anne Thompson in Entertainment Weekly, who nicely encapsulated just what a sensation the movie was. "Jurassic Park is bigger than its stats," she wrote. "It's bigger than its record-breaking opening weekend ($47 million). It's bigger than its record pace in reaching $100 million (9 days) and $200 million (23 days, 14 days faster than Batman, the previous record-holder). And it's bigger than its potential to reach $330 million (the industry's current best guess), which alone would make it the second most successful film of all time, ahead of Star Wars ($322 million, including rereleases) and behind E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial ($399 million, from its two releases)." She estimated that Spielberg could himself make $100 million off the film. "[H]ow big is Jurassic Park? Try this on for size: It's the future," she predicted. "It has changed moviemaking in Hollywood forever — or at least until the next Jurassic comes along."

Summer-movie sensations were nothing new back then, but Jurassic Park indeed felt different. Like Jaws or Star Wars or Batman, it seemed like the heralding of something new in event movies. If Terminator 2 had demonstrated CGI's promise, Jurassic Park cemented the technology's importance. Suddenly, anything — even realistic dinosaurs — were possible on the big screen. Filmmakers who had previously balked at pursuing certain projects because they weren't feasible suddenly saw that they were possible. (Perhaps the most famous example was Stanley Kubrick's decision to go forward with his long-simmering A.I. Artificial Intelligence after seeing what Spielberg had achieved.) But the film also encouraged audiences to accept no substitutes: If a potential blockbuster didn't have this cutting-edge CGI, why even bother making it?

Of course, that mindset has had its downsides over the last 30 years. Now, even the most mediocre sci-fi film is lathered with CGI, inundating audiences with phony environments and digital characters that can give a movie a distancing feeling of utter unreality. People in movies can now do just about anything because of the technology, which inherently makes movies less magical. (If everything is possible, how do you wow an audience?)

But Jurassic Park's success also created the next era of amusement-park cinema. To be sure, people have always complained that movies were pointless spectacles. (Spielberg had to endure a lot of this blowback when he made Jaws.) But Thompson's article, written during the summer of 1993, anticipated what was to come. She spoke with box-office tracker Michael Mahern about Jurassic Park's commercial prospects, and he made this surprising comment: "What if Jurassic had the childish wonder of E.T. or the mythopoetic elements of Star Wars, or the sheer dramatic craft of Jaws? What if it weren't just a roller-coaster ride? Old ladies went to see E.T. They're not going to Jurassic Park." Even Kathleen Kennedy, who had produced E.T. and Jurassic Park, admitted, "I'm not sure I want it to pass E.T. [on the box-office charts]. E.T. is a special little movie to me."

Her reservation spoke to a collective reaction to Jurassic Park: Sure, it's a lot of fun and looked amazing … but it's not special like Spielberg's best popcorn films. It was an astounding technical achievement but also a little mechanical. It was Spielberg, his generation's most fabulous commercial filmmaker, doing his old tricks one more time, but without the same level of surprise or giddy delight as before.

Not that any of that mattered: The film generated two sequels, and then the 2015 reboot/sequel Jurassic World and its sequel. Spielberg created a mammoth franchise around not a human actor but a concept: Dinosaurs are scary and rad. (A few years ago, I actually argued that any of us could be the star of one of these movies and they'd still be a massive hit. As long as they have T. rexes in them, people will buy tickets.) Jurassic Park was a phenomenon, and it still casts a long shadow. Spielberg's film drew inspiration from the old King Kong and Godzilla pictures, but those modern monster movies are now taking their cues from what Spielberg concocted. Jurassic Park is now part of every big film you see. By comparison, nobody has talked about Last Action Hero for decades — unless it's in connection to how much it got trounced by Jurassic Park.

Has it held up? The film won three Oscars, in effects and sound categories, and all of that actually still plays really well. Sure, the CGI technology has improved exponentially since 1993, but it holds up nicely. And the movie remains an enjoyable, imperfect blockbuster — and certainly better than the sequels that came in its wake.

But as much as Last Action Hero will be associated with Jurassic Park, unfortunately for Schwarzenegger, there's another movie whose legacy will also always be tied to that dinosaur spectacle. After completing 1991's Hook, Spielberg wanted to make a serious movie about the Holocaust, but was persuaded by Universal to do Jurassic Park first. After that, he got the go-ahead to direct Schindler's List, which came out about six months after Jurassic Park. (In fact, Spielberg was overseeing the editing of Jurassic Park while filming the drama.) And for all of us who feel that Jurassic Park seemed to lack the heart of Spielberg's best blockbusters, well, Spielberg probably agreed. His mind was on Schindler's List, a movie far more important to him.

"Films like Color Purple, Empire of the Sun, and Schindler's List quadruple my satisfaction," he said around Schindler's List's release. "Jurassic Park didn't challenge me a tenth as much as Schindler's List did. And even though I sometimes look upon that as selfishly indulgent, those are the kinds of subjects I am now finding fill me up the most."

That same Oscar where Jurassic Park took home three awards, Schindler's List won seven, including Best Picture and Best Director, permanently establishing Spielberg's bona fides as a "serious" filmmaker and not just an expert pop craftsman who made Jaws and Jurassic Park. Sid Sheinberg, the head of Universal, told the Los Angeles Times back in '93, "Schindler's List is a masterpiece and I have never said this before, I assure you, on any motion picture. It will be in my memory long after the gross of Jurassic Park has faded."

In subsequent years, Spielberg has continued to go between spectacle and seriousness — for every War of the Worlds, there's a Munich — but, in some ways, Jurassic Park doesn't even feel like his movie anymore. It now belongs to the dozens of memes it produced, and the deathless Jeff Goldblum impressions that people do mimicking his character Ian Malcolm's odd, ironic speaking style. It's been absorbed into the culture, its every element now known by heart. When Crichton conceived the original book, he wanted to sound a warning about technological advancement. He couldn't have known what his prose would help unleash upon the world.

Tim Grierson is the co-host of The Grierson & Leitch Podcast, where he and Will Leitch review films old and new. Follow them on Twitter or visit their site. His new book, This Is How You Make a Movie, is out now.