Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

When Marvel Comics had to go beyond The Empire Strikes Back (but not too far)

Imagine an ongoing comic-book series in which the main hero can never battle the main villain, and can have no romantic involvement with the female lead — the only woman in the regular cast; one of the most popular characters becomes unavailable for years; and the immensely talented writer/editor who has been at the helm for most of the run decides to leave. You might think that series was doomed. In many cases, you’d be right. But in 1980, when the monthly Star Wars title published by Marvel Comics ended up in that very situation, not only did it confront those significant creative challenges successfully, it actually thrived.

The series had been around since early 1977, launched by writer/editor Roy Thomas and artist Howard Chaykin with a six-issue adaptation of the original movie. Thomas and Chaykin then crafted a new storyline focusing on Han Solo and Chewbacca that ran in Issues #7-10, after which both men departed. Writer/editor Archie Goodwin and artist Carmine Infantino took over with Issue #11.

Goodwin, who died in 1998, was unquestionably one of the best writers and editors ever to work in the comic book industry. He guided Marvel’s Star Wars series through a long run of stories that expanded the universe, introduced new characters and concepts, and planted seeds for the then-upcoming second movie, The Empire Strikes Back. For example, Goodwin and Infantino showed, in Issue #35, how Darth Vader learned of Luke Skywalker’s existence.

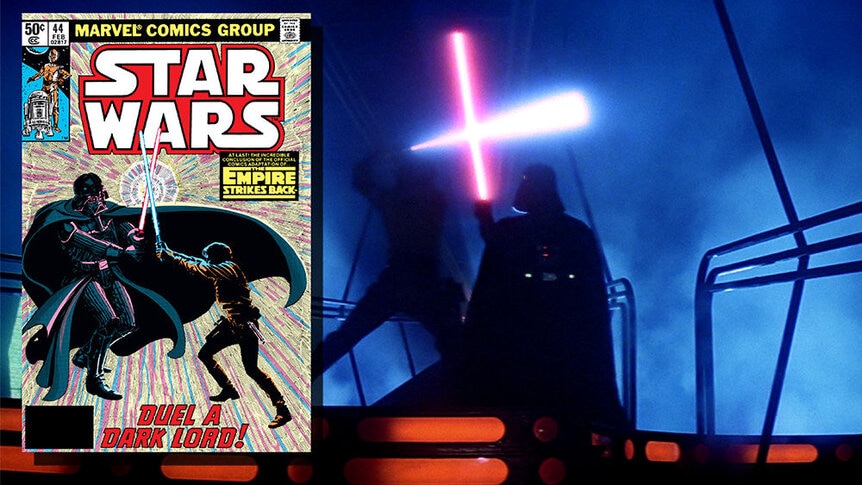

Once the series reached its 45th issue, however, it had to deal with the aftermath of the second movie. The Marvel adaptation of Empire, written and edited by Goodwin and illustrated by Al Williamson and Carlos Garzon, ran in Issues #39-44. Like the movie, the comic version left the characters — not to mention the audience — reeling, what with Vader declaring that he is Luke’s father, Han frozen in carbonite and taken away by Boba Fett for delivery to Jabba the Hutt, Luke losing his hand and getting a cybernetic replacement, and Leia professing her love for Han (does she really love him, or will she end up with Skywalker after all?). The comic was left in a unique — and unenviable — place. It couldn’t resolve any of those dangling plot threads, as the next movie would do that. But the comic couldn’t just spin its wheels for the next three years, either. Goodwin was the ideal person to write the series during this uncertain time.

But that was the moment Goodwin stepped down, to focus on his duties as editor of Marvel’s brand-new magazine, Epic Illustrated. Incoming editor Louise Simonson (Louise Jones at the time) had her work cut out for her. Goodwin stuck around for a little while, contributing a handful of stories over the next six months, including the special double-sized 50th issue. During this period, he presented a Luke Skywalker who was just as unsure as the audience was about whether Vader was telling the truth about his father. As Luke himself noted in Issue #45, the idea that Ben Kenobi had misled him was “unthinkable.” (In that same issue, Goodwin also inserted something of a continuity conundrum: He showed Luke somehow reunited with his lightsaber, which of course Skywalker lost when Vader chopped off his hand. Luke would continue to use this lightsaber in subsequent issues.)

During this time, J.M. DeMatteis, Larry Hama, and Mike W. Barr each contributed a one-shot tale to keep the series going as editor Simonson looked for a new regular writer. The one constant was Infantino, whose storytelling was always beyond reproach — though to Star Wars purists, he never drew the characters to look like the actors who played them, and never depicted the ships, weapons, and technology the way they appeared on film. When Williamson and Garzon produced the Empire adaptation, they made a concerted effort to capture the look and feel of the live-action incarnation, marking a major shift in the art style of the comic. A new standard had been set, and Louise Simonson made it a priority to meet that standard regularly.

“I knew what Lucasfilm liked, and what they really liked more than anything else in the world was Al Williamson’s artwork,” she says. “But it was impossible for us to get Al [as the regular artist] because he was very slow — there was just no way. So I did the best I could to make the book look that good.”

To that end, with Issue #49 she brought on penciler Walter Simonson, her husband, who was then well on his way to becoming one of the most popular artists in the industry, and paired him with inker Tom Palmer. With his photorealistic inking style and talent for capturing likenesses and technical accuracy, Palmer played a key role in helping Louise Simonson achieve her vision for the series. “Tom was great,” she says. “You could have done stick figures and he would have turned it into something genius.”

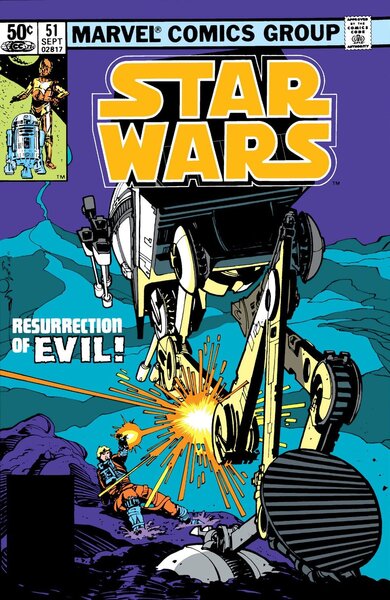

With Issue #51, the series had a new regular writer, David Michelinie. “I was a huge Star Wars fan,” he says. But coming aboard turned out to be a bigger challenge than he had anticipated. Given the end of Empire, the Marvel team was faced with the following rules from Lucasfilm: Luke and Vader could never come face to face; Luke and Leia’s relationship could not progress in any way; Han, Boba Fett, and Jabba were off limits (though Han did appear, via flashback, in Issue #50 and 1982’s Star Wars Annual #2); Luke could not further his Jedi training; and Yoda and Kenobi could not appear (aside from a dream sequence in Issue #50).

Nevertheless, the new team aimed to start off with an ambitious two-parter — only to cause Marvel to get a rare rejection notice from Lucasfilm. The proposed storyline involved the Empire building a second Death Star, without the design flaw that allowed Luke to destroy the original. According to Louise Simonson, Lucasfilm’s response was “You can’t do that. We can’t tell you why, but you can’t do it.”

Michelinie saw the rejection as a major clue. “When the idea of creating a second Death Star was bumped, I was kind of like, ‘Cool! Guess what’s going to happen in the next movie?’ I kind of enjoyed that,” he says.

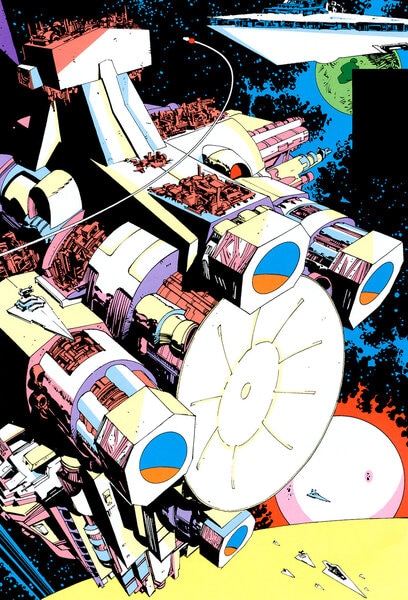

The team’s solution: Have the Empire build what was basically a giant cannon in space that could blow up planets. Lucasfilm approved. “We did exactly the same story we would have done, except we called it the Tarkin — it was really a Death Star, without a circular cover,” Walter Simonson says.

One of the main highlights of the Tarkin story was a sequence in which Luke and Vader almost cross paths and Vader displays just how powerful he is when an airlock opens behind him and he is nearly sucked out into space. The airlock, incidentally, was opened intentionally by one of Vader’s own men, in retaliation for all of the Imperial officers Vader executed during The Empire Strikes Back.

Under Michelinie and Simonson, the series moved forward and gained momentum, as it had under Goodwin. “It was kind of like going on side streets,” Michelinie says. “I figured, as long as all the streets came back into the main drive when the next movie came out, I could move a little bit to the side as we were going along the road.”

The creative restrictions drove them to be more original and innovative. With Vader limited to rare appearances — he only showed up twice during the 18 months that Michelinie served as writer — there was an emphasis on introducing new villains and threats. The Rebels faced a variety of ambitious Imperial officers, strange malevolent alien creatures, and merciless slavers. The search for Han was put on hold, under the rationale that the Rebels needed all available personnel (and ships) as they searched for a new location for their main base of operations. That brought Lando Calrissian and Chewie back into the fold on a regular basis, allowing Lando to develop a relationship with each of the original cast members. When the search for Han finally resumed (in Issue #68), bounty hunters — including the ones seen briefly in Empire — became a recurring threat. Leia even encountered someone who at first appeared to be Boba Fett, but turned out to be an old colleague of his, named Fenn Shysa.

Micheline and Simonson created the illusion of change — things seemed to happen, the characters appeared to grow in new ways, but nothing was done that could interfere with or contradict anything in the next movie. For example, Luke and Leia appeared to grow closer and more affectionate, but there was nothing romantic about it unless a reader really wanted to see it that way. The Rebels established a new base on the planet Arbra, where they joined forces with small, telepathic, rabbit-like creatures called hoojibs.

Most significantly, Luke began a relationship with a female Rebel pilot named Shira Brie, which aroused misgivings in Leia and ultimately led to disaster when Shira’s ship was blasted to pieces. And Luke, guided by the Force, was the one who fired the shot. This launched the popular “Luke Skywalker: Pariah” saga that ran through Issues #60–63. Believed by a growing number of Rebels to have killed Shira out of carelessness or even malice, Luke found himself essentially shunned, and began to doubt himself and the Force. The disaster even tested the strong bond between him and Leia. So Skywalker began a personal quest to learn the truth and determine if he could ever trust in the Force again, leading him to seemingly fall right into the clutches of Darth Vader.

“That storyline really played with the characters,” Michelinie says. “Did the Force really betray Luke? I was able to stretch the subplots over several issues, and I think it paid off well.”

Walter Simonson also considers the storyline a high point. “I wanted to push the ‘Pariah’ story at least an issue or two longer!” he says.

The series experienced another major shakeup when Walter Simonson left with Issue #66 to focus on other projects. Michelinie departed three issues later. Louise Simonson turned to Jo Duffy, who had previously written Issue #24 — a tale of Obi-Wan Kenobi in the days of the Old Republic — to take over as writer. Duffy was paired with artist Ron Frenz, a relative newcomer at the time, who had already penciled Issue #67. Palmer remained as the inker to help maintain the distinctive, rich, cinematic look and visual accuracy that the series had achieved.

Issue #71 began a long storyline that planted the seeds for Return of the Jedi but also took the series in new directions. One of Duffy’s first accomplishments was to kick the search for Han into high gear, sending Luke, Leia, Lando, Chewie, and the droids across the galaxy to investigate various leads. This coincided with the search for a pair of missing Bothan spies who disappeared while trying to bring to the Rebels stolen information about the Empire’s latest super-weapon. (Guess what it is.)

In a bit of déjà vu for the series, Duffy and Frenz had the same experience on one of their first stories that Michelinie and Simonson had with their “second Death Star” tale. For Issue #73, the cast was supposed to visit a world populated by small, furry creatures, called Lahsbees, who used primitive hang gliders for transportation. Lucasfilm demanded extensive changes to the creatures, but wouldn’t say why. Of course, Duffy and Frenz had inadvertently anticipated the Ewoks. “I couldn’t figure out why Lucasfilm gave me such a hard time about the Lahsbees — until I saw the script for Return of the Jedi,” Duffy says.

“In the initial design of the Lahsbees, they were sort of gremlin-like, with really wide eyes,” Frenz recalls. “They ended up being very feline-like in the printed book. It was funny — Lucasfilm had to tell us how to fix them without giving too much away, because they didn’t want information to get out about the Ewoks. And they freaked out about the hang gliders.”

Duffy, like Michelinie before her, also seized the opportunity to further develop Lando, far more than the movies ever did. Despite his superficial similarities to Han, Calrissian was shown to be more egotistical, more stylish, and possessing an even greater potential for comedic moments.

“Lando was a riot,” Duffy says. “Heroic, tough, dedicated — and also kind of conceited, and that makes it really fun to set him up and knock him down a peg. I had a great time with him.”

Duffy could also adopt a darker, more serious tone, as she did in Issue #80, in which Luke, Leia, and C-3PO search for one of the missing Bothan spies at an Imperial stronghold. There they encounter the spy’s droid, LE-914, with whom C-3PO establishes something of an emotional bond before the story comes to a tragic conclusion — one that demonstrates the depths of Darth Vader’s cruelty and leads directly into Return of the Jedi.

With that issue, the post-Empire Strikes Back era of the comic series was officially over. Despite the creative restrictions placed upon them, the Marvel team managed to produce a satisfying body of work that stands as the connective tissue for two of the most beloved movies of all time.

“It was difficult trying to maintain interesting stories that tied in with the movies without actually moving either the characters or the situations any way but sideways,” Michelinie says. “But it was a fun challenge.”

-------

Marvel’s complete 1977-1986 run of Star Wars comics is currently being reprinted in the trade paperback series Star Wars Legends Epic Collection: The Original Marvel Years.

This article is dedicated to the memory of Charles Lippincott (1939-2020), who brought Star Wars to Marvel in the first place.