Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Nerdy Jobs: Storyboard artist Doug Lefler creates what you see on the big screen

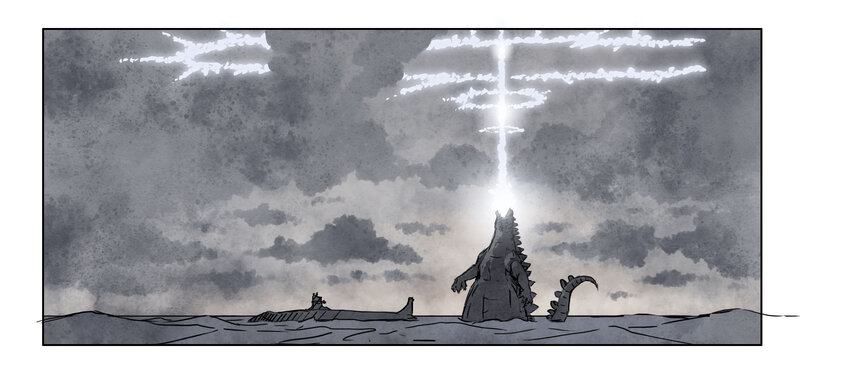

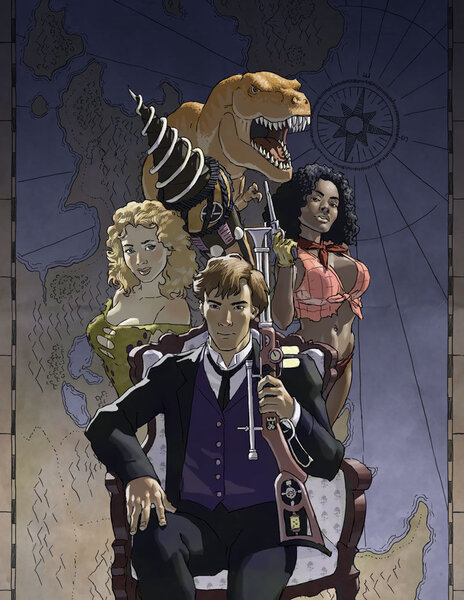

Before the stories you love end up on the big screen, storyboard artists take a script and translate the words into visual storytelling. Often the shots you see on the screen come first from the minds of the artists. Doug Lefler started back at the California Institute of the Arts, in their brand-new animation program, along with John Musker, Brad Bird, and Jerry Rees, a class that helped reshape the entire industry. In addition to being a writer, a comic book creator and a director, Lefler has been head of story for a number of films. He worked on Spider-Man, Army of Darkness, The Last Legion, Legendary's Godzilla, and Xena: Warrior Princess, to name just a few.

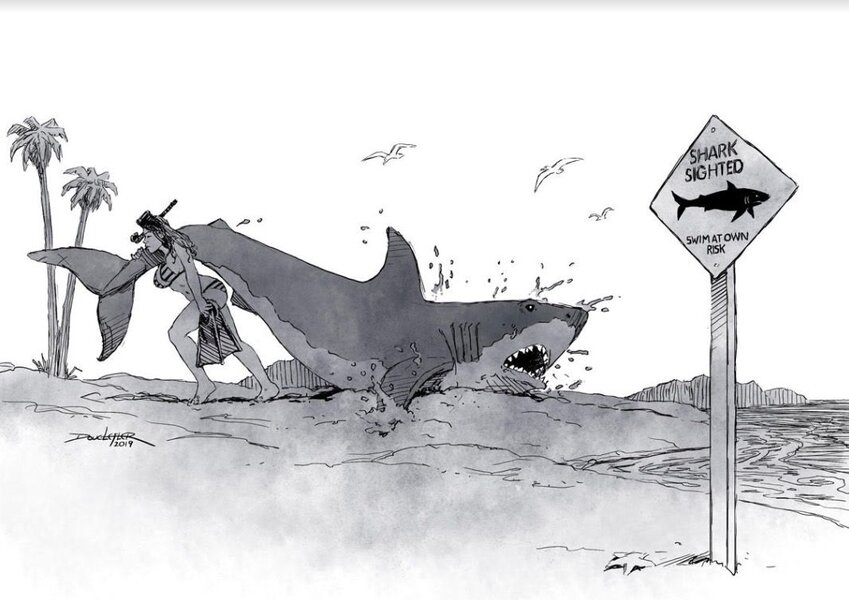

Lefler is the head of the story department at The Third Floor, a visualization company that does pre- and post-production on films from Marvel, Disney, and the Star Wars films. He is also the head of Story Attic, the original content division of The Third Floor. He also created Scrollon, an original digital comics platform that allows for comics to tell stories without borders, or what's known as an infinite canvas. He told SYFY WIRE all about his unusual entrance into the industry, what it's like to draw for a living, what he's looking for when he hires artists, and advice to anybody out there who wants this sort of nerdy job.

How did you get started in the industry?

When I was a kid, I'd love to draw, but I was never interested in drawing landscapes, or portraits, or still lifes. I was always interested in what would happen if you put two or more images together in a sequence to tell a story. I was interested in either working in comic books or in movies, and because I lived in Southern California, Hollywood was closer than New York. So I decided I should try to go into the film industry.

I focused my efforts on that. I was lucky enough to get accepted into California Institute of the Arts, into their fledgling character animation program. I was brought into that the first year that it was in existence and was there for two years, until 1977, when I was hired at Disney along with John Musker, Jerry Rees, and Brad Bird.

It was the year Star Wars came out. It was a very exciting time to be beginning your career in the film industry. I focused on writing and drawing in the story department, and the great thing about being at Disney was that the animated feature films were written in the storyboard process. So I had good training on how to write with pictures, working on The Fox and the Hound and The Black Cauldron while I was there. Then I did some work on The Little Mermaid after I left Disney in the early '80s.

When I was at Disney, I never actually intended to be in animation. I'd loved animation, but I had always wanted to work in live-action films. Like when I was younger I wanted to be Ray Harryhausen, and I thought if I could work on films like he made that I would die happy.

When I was trying to figure out how I could get out of, or transition from, feature animation into live action, I thought at the time that storyboarding would be a good way to do it, since I was drawing storyboards anyways. I learned at the time there was a guy who was storyboarding a feature film at Disney. That film was Herbie Goes Bananas. It's probably one of the least admirable films in the Herbie franchise. I asked him if I could come talk to him about going live-action storyboards, and he was gracious enough to give me some time and answered all my questions.

What he told me at that time was that storyboarding was a dead-end job. He said it paid fairly well, but he had to warn me that if I went down that road, there was no turning back and I would never be able to do anything but draw a storyboard, so I wouldn't do production design or any art dragging or anything else. When you became a storyboard artist, that's all you did, and you can't ever escape it. After that, he also gave me a lot of really practical advice on how to draw storyboards, but when I left his office, I remember thinking how lucky I was that I talked to him before I made a horrible mistake and became a storyboard artist after leaving Disney.

So I focused on writing and on illustrating and doing other things, and I avoided storyboards for many years. And then, eventually, I ran out of money and a good friend of mine, Bill Kroyer, offered me a storyboarding job on a music video. At that time, I thought, "This may be a terrible mistake, but I need the money, so hopefully this won't ruin my career." I accepted this job and I was storyboarding a music video for Chicago called "Stay the Night."

I had never storyboarded a live-action film before, but I found that from the first day that I did that job, I had a completely different experience than the veteran storyboard artist who had advised me years before had warned me about. I found that I was having a substantial influence on the outcome of the product, that people were listening to my ideas. And, for me, being a storyboard artist led to a lot of other things, including writing and directing and occasionally producing.

I don't think that that veteran storyboard artist lied to me when he told me what the restrictions of the job were. That was just his truth. And I had a different truth. It may have been because the industry had changed, times had changed, and it probably had something to do with what I was bringing to the job. I think that one of the reasons I was able to excel as a storyboard artist was because I loved drawing, I loved storytelling, and I loved filmmaking. And those are the three component parts of being a good storyboard artist. And they served me well, and it led to a lot of other opportunities.

For somebody who isn't really that familiar with storyboarding, how would you explain the job?

Our job is not to illustrate the script. Our job is to translate the script from a written language into a visual language. That's something that not all storyboard artists grasp, but a language teacher once summed it up well for me while I was trying to explain it to her what I did. "It sounds like translating poetry, where if you do a word-for-word translation, you'll kill the poetry," she said. "You need to be true to the ideas, not to the specific details that are in the script."

And that's very true, that the language of writing a script is different than the language of looking at a film. If you actually wrote a script the way you are going to film it, it would be unreadable. You have to condense things, you have to abbreviate things, and you have to convey them in a language that's accessible and not too fraught with detail.

So the job of storyboarding, it's kind of like drawing a comic book for a movie, but you're focusing on the mechanics of how you actually will shoot something, how the camera will be incorporated into the shots. You solve problems for safety and for cost reasons, how you can shoot stuff safely, how you can shoot visual effects effectively, and you are there to service a story and you're there to serve as the director and make his or her job easier when they walk on the set.

What would you consider the best part of the job?

Being paid well to draw for a living. One of the greatest things, I think for those of us who love to draw, it that storyboarding is a good way to make a living. I should actually amend that — it depends on what you like to draw. I know there are a lot of illustrators who've gotten into storyboards who have been frustrating because they feel they never have enough time to finish an image and make it look as pretty as he wanted to. And that's true when you're storyboarding, you have to think of each frame as a brushstroke and not as a complete work of art. And that the total composition is a sequence or ultimately a completed film.

What would you say are the biggest challenges?

Well, as I said, there are three component parts of the job. You need to understand drawing, you need to understand filmmaking, and you need to understand writing. Most people don't bring all three of those disciplines. In some ways, they're contradictory to one another, because drawing is thinking spatially, and writing is thinking linearly. So whatever your weakness, and you just need to focus on that more than the others. As I said, I think I was going to bark for the job because I always liked all three of those, and I love the problem-solving aspect of filmmaking and I loved the writing aspect of storyboarding. A lot of what we are doing is a visual rewrite of the script.

When you're hiring a storyboard artist, what do you look for?

Well, interestingly enough, drawing ability is important, but it's only, it's most important up to the extent that you have the skill to convey your thoughts clearly. Beyond that, most of what we do we can do with stick figures and arrows. So the ability to draw anatomy and perspective is the thing that you use to get a job, but it's not always the most important thing that you need to do the job.

I really look at whether or not artists can convey a dramatic idea and, you know, sequences of images and get the audience emotionally engaged. A lot of the process of getting the audience emotionally engaged, for the storyboard artist, is similar to what it is for the writer. You need to ask compelling questions with your imagery that makes people want to know the answers to how something is going to be resolved, what a character might be thinking when the specific event occurs. The job is to get the viewer engaged. So I look for that ability when I'm looking to hire another artist.

What sort of advice would you give somebody who would like to get into this?

Oh, learn to draw, learn to write, and learn the mechanics of filmmaking. Yeah, you can kind of break storyboarding down to "make it read," "make it engage," and "make it work," which really come down to drawing, writing, and filmmaking, respectively. And drawing is important. It helps if you do enjoy it, but mostly you need to understand how to tell a story with pictures, how to engage an audience with a sequence of images, and how to ask or pose compelling questions with your pictures.

Tell us about the work you do at The Third Floor.

I am head of the story department at The Third Floor, which is the largest visualization company in the world at this point. We work on most of the Marvel films, a lot of other Disney films, and Star Wars movies. A lot of big visual effects, complicated films, but we also get to work on smaller films. I just recently was drawing storyboards for a low-budget horror-suspense film, which was really fun. A lot of times it's fun to solve small problems as well as big problems. You have to be smarter with the smaller budgets than you are with the big budgets.

You also created a comic format called Scrollon. Can you tell us about that?

Scrollon is a digital comic format I invented some years ago when I was interested in doing my own digital comic and I didn't like any of the formats that I saw that were currently available. Scrollon was designed to be native to the digital world. So it is designed to work on tablets, phones, and laptops, but particularly on phones and tablets. Scrollon has no pages or borders, yet it is like an infinite canvas idea, where you scroll through the image and the process of moving through the image is part of the storytelling language.

It was inspired by an idea that I had had when I was in art school in the mid-'70s. One of my professors took us to the art museum and showed us a Chinese scroll painting that was just one very long landscape on this scroll, but it was uninterrupted by any breaks and pages or borders with the edge of the canvas. You just kept rolling through it, and it was such an immersive experience to look at a story this way. To look at an image this way, at that time, it occurred to me, would be a great way to tell this story, but at that time in the mid-'70s, I couldn't think of any way to publish something. A drawing that would be, like, six inches high by 50 feet long. So I tabled the idea for a few decades. And then when I was looking for an idea on how to do digital comics, I remembered this experience of seeing this Chinese scroll painting and I developed Scrollon based on the experience I had looking at that painting.