Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Problematic Faves: Sin City

"My city. She's always there for me. Every lonely night, she's there for me. She's not some tarted-up fraud all dressed up like a piece of jail bait. No, she's an old city, old and proud of her every pock and cracks and wrinkle."

This piece of highly questionable writing isn’t from Sin City. It’s part of the opening narration to The Spirit, the excruciatingly bad adaptation of the legendary Will Eisner's iconic comic series of the same name. Anyone familiar with the Spirit stories will know that the movie has basically nothing to do with Eisner's work. It's an incomprehensible, deeply robotic pile of noir tropes, misogyny, and genre pastiche that's utterly lacking in self-awareness. So, of course, it was written and directed by Frank Miller.

Three years prior to the release of The Spirit, Frank Miller received a new generation of fans and revival of critical acclaim when the cinematic adaptation of his Sin City graphic novels premiered to great success. Miller co-directed the movie with Robert Rodriguez, and even Quentin Tarantino dropped by to guest-direct a scene. Rodriguez, a die-hard fan of Miller's work, was so determined to give Miller a co-directing credit for the movie that he resigned from the Directors Guild of America, whose rules forbid such a call. Sin City was an undeniable success in almost every way: It had its worldwide premiere in competition at the Cannes Film Festival, it grossed four times its budget, and the reviews were strong across the board. In 2005, Sin City felt like a breath of fresh air, a dazzling and uncompromising visualization of Miller's hard-bitten pulp style. Made three years before Iron Man changed the game in terms of comic book movies, Sin City felt like a new peak for what the genre could do. It's a visually strange and hypnotic world of the unreal, a movie of visceral ecstasy that works entirely by its own rules.

I love it even more than I love graphic novels, and boy, that can be a difficult task when you’re trying to be a good feminist.

Frank Miller is one of the true undeniable icons of modern comic book fiction. His gritty, old-school pulp-inspired storytelling helped to drag the medium into the modern day with bleak, unabashedly political, and abrasive tales that made the great heroes of comic lore into something far darker and gritty. Sin City, first published by Dark Horse in 1991, gave Miller a chance to create his own worlds free of the DC and Marvel rulebooks. Part 1930s gangster movie, part Dick Tracy, part Taxi Driver, the world of Basin City was one straight out of a noir movie, albeit one not dictated by the constraints of the Hays Code. These are stories of the underworld of crime and its own bastardized form of justice, one where ideas of good and evil are indistinguishable from one another. If you, like me, have a great love for old-school noir movies, ones where black and white is shot in sharp contrasts and smoke fills every scene and the dialogue is near-baroque in its poetry, then Sin City feels designed for you.

Of course, loving Sin City is easier said than done sometimes.

There's a famous webcomic courtesy of Shortpacked! that shows Frank Miller flanked by two shadowy figures who challenge him to "write a story with a female character who is NOT a prostitute." After a few moments of silence, he immediately begins typing, "whoreswhoreswhoreswhores" and so on. It’s a hilarious and beautifully accurate summary of one of Miller’s biggest issues as a writer: He loves to write whores and dames, but when it comes to fully fleshed-out female characters, he straight-up sucks.

This is not exclusive to Sin City, where practically every female character is a hyper-sexualized sex worker defined entirely by their sexuality (and status as punching bags for men). After all, as evidenced by our opening paragraph, this is the man who can sexualize a city. His take on Wonder Woman reduced her to a bitter man-hating borderline-militaristic figure of mockery ("Out of my way, sperm bank!") who still needs a big strong man to force her into her place. A lot of his “re-imaginings” of iconic superhero women rely on making them sex workers who only ever talk about, think about, and live to be sex objects. Even Alan Moore famously called out Miller’s bigotry, describing Sin City as “unreconstructed misogyny” and describing his graphic novel 300 as "wildly ahistoric, homophobic and just completely misguided" (Miller's Islamophobia also came to the forefront with his work The Holy Terror, a comic about a costumed vigilante who takes on a group of Islamic terrorists, which Miller himself called a "piece of propaganda.")

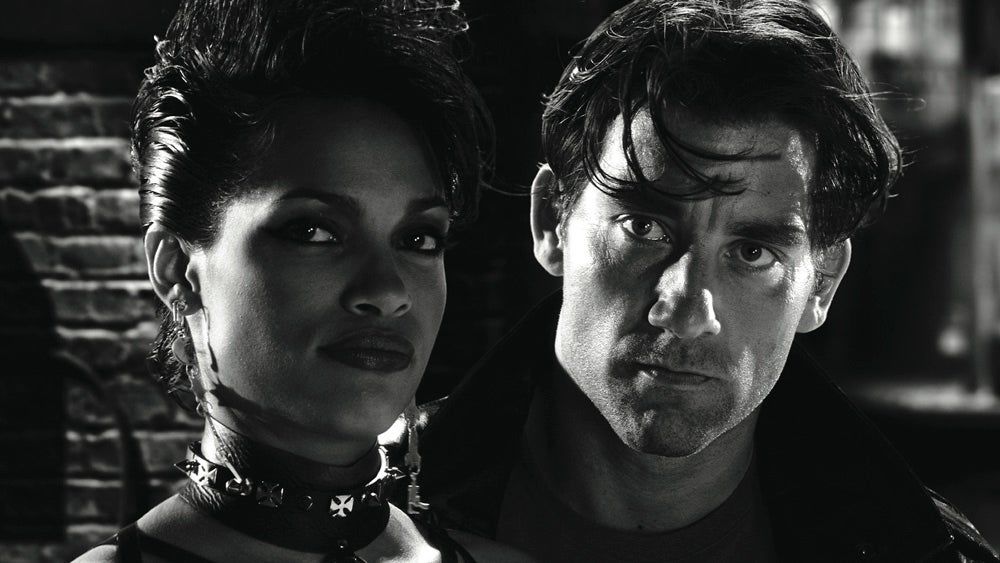

Watching and reading Sin City as pieces of pure fantasy make for a more enjoyable and less emotionally draining read. The women of this world are full-on Strong Female Characters, the kind of kickass fighting f**k toys that men love to call the true embodiment of empowerment. They’re almost always scantily clad in ways that defy the conventions of mere fabric. Their interactions with men are given the thinnest sheen of independence right until they’re beaten in the face or assaulted or crumble to the feet of those who demand submission. Rosario Dawson as Gail, the leader of the Old Town's sex workers and the on-off lover of Dwight (played by Clive Owen), is a prime example of this. She demands allegiance and loyalty from her girls (who are always girls and never women) and kills a hell of a lot of men in deeply violent manners. Still, when Dwight slaps her, she doesn't fight back: She kisses him. There’s an easy-to-enjoy fantasy right there, where the women are all gun-toting and hot as hell. It’s power in a way that doesn’t challenge entrenched structures or assumptions, but the visceral pleasure of it is undeniable.

The women of classic noir are often alluring, morally ambiguous, and two steps ahead of the men in the story. These were prime roles in the golden age of Hollywood, a chance for actresses to be something other than ingenues and housewives. There are subtleties and layers at play, even in the most stock stories. Miller’s work is far starker by design, which has its appeal, but when it comes to creating female characters who are more than one quality, Miller doesn’t even bother. In his world, men are men and women are broads. It’s not so much retro sexism as it is a near-parodic version of that concept, only without the jokes. Sin City, like a lot of Miller’s later work, took a noticeable downturn in quality as his stories became more like self-parody. The blunt noir-style dialogue became incoherent, the characters rooted more in pantomime than reality, and the artwork near-indecipherable. Miller himself has only gotten more politically right-wing, and his work is often deeply laughable when it’s not outright unnerving in its bigotry.

So, why do I still like Sin City? Why do I keep returning to it, even as increasingly large swaths of the comics and movie make me uncomfortable beyond reason? There’s something about the sheer gut thrill of it all that I find hard to ignore. Basin City is a world of horrors where everyone seems delighted to be rolling around in the filth of it all, albeit a kind of grime that looks stunning thanks to the obsessively detailed work done by Rodriguez and Miller to painstakingly recreate the panels of the graphic novels. This feels like a world just removed enough from ours to give me a kind of comforting shield from reality when I engage with it. The aesthetic is inherently distancing in a helpful manner. Real life doesn’t look that black and white, so it’s easier to consume. Truthfully, I like a lot of those female characters too, especially Gail. Are they ridiculous parodies rooted in misogyny? Of course, but we women are used to extracting good qualities from bad work. Not even Frank Miller can stop that.