Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

Study: Playing Pokémon as a kid may have helped your brain…evolve

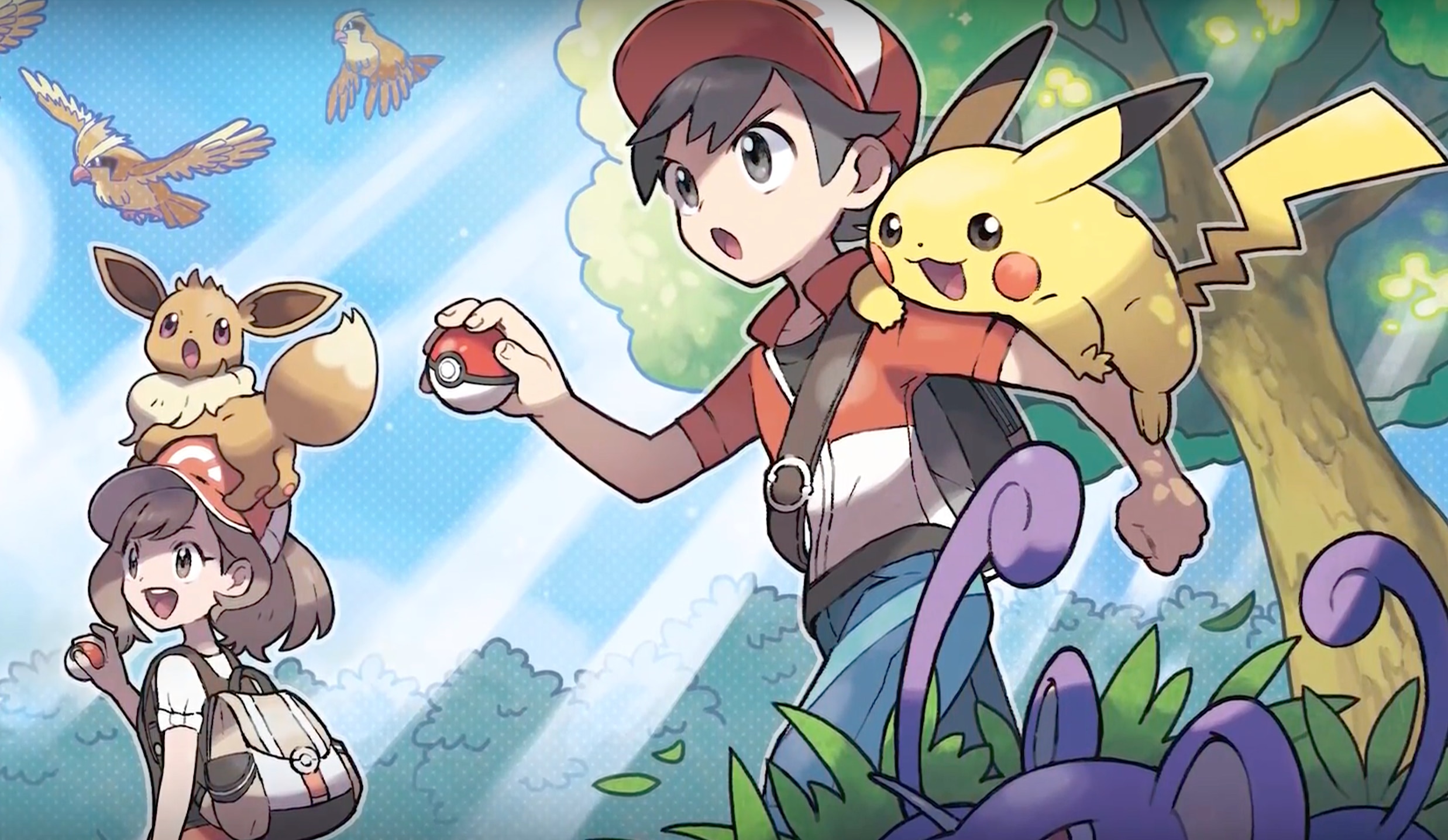

We just knew we were doing something right all those years ago when we couldn’t put our Game Boys down. Thanks to science, anyone who was ever accused of rotting their brain playing Pokémon (and for our purposes, we’ll accept any color variant) can now whip out a new Stanford study that shows all those hours with Pikachu and pals may have actually helped our minds … evolve.

In part the work of self-confessed childhood Pokémon fan and present-day neuroscience researcher Jesse Gomez, the study compared the brain scans of adults who were avid Pokémon players as children with a control group of grown-ups who didn’t know their Pikachu from their Poliwag. (Duh! One’s electric; the other’s water!)

By mixing in images of original 1990s-era Pokémon characters with standard, everyday pictures of objects like animals and cars, Gomez and research partner Michael Barnett put 11 confirmed childhood Pokémon aficionados through a series of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scans and compared what they saw with scans from the non-Pokémon control group.

The result? “[T]heir brains responded more to the images compared to a control group who had not played the videogame as children,” Stanford reported in announcing the finding. “… The site of the brain activations for Pokémon was also consistent across individuals. It was located in the same anatomical structure — a brain fold located just behind our ears called the occipitotemporal sulcus. As best the researchers can tell, this region typically responds to images of animals (which Pokémon characters resemble).”

While discovering a “Pokémon region” in the brain mainly confirms previous research that suggests childhood is the prime time for our ability for sophisticated visual pattern recognition to develop, the thing that surprised the researchers — and especially Stanford’s Kalanit Grill-Spector, who helped secure funding for the study — was just how tailor-made Nintendo’s original gameplay formula turned out to be at serving up a rigidly consistent set of variables.

“I thought, ‘This is never going to work,’” Grill-Spector confessed, before realizing that Nintendo’s handheld platform offered up a lot of consistency from one test subject to the next: the same imagery, presented in the same format, to people who encountered the images at around the same time of life — and always viewed at an arm’s-length distance from the players’ faces.

But what you really want to know, we’re guessing, is whether running down your Game Boy battery all those times, just to put the final touches on your immaculately curated Pokédex, actually had the unintended consequence of turning you into a smarter, happier, more successful grown-up — and whether today’s moms and dads should fret over all the screen time their kids may still be spending.

“I would say to those parents that the people who were scanned here all have their Ph.D.s,” Gomez noted in the study summary. “They’re all doing very well.” Are we guilty of confirmation bias if we wholeheartedly agree?