Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

This Week in Genre History: The Matrix red-pilled us 22 years ago and changed everything

Welcome to This Week in Genre History, where Tim Grierson and Will Leitch, the hosts of the Grierson & Leitch podcast, take turns looking back at the world's greatest, craziest, most infamous genre movies on the week that they were first released.

When budding screenwriters Lana and Lilly Wachowski were trying to break into Hollywood in the early 1990s, they worked on a script that was incredibly ambitious but also powerfully philosophical. "[We were thinking] about 'real worlds' and 'worlds within worlds' and the problem of virtual reality in movies," Lana later told The New Yorker, "and then it hit us: What if this world was the virtual world?"

We've lived in the Wachowskis' world ever since. On March 31, 1999, The Matrix opened in theaters, and it's not hyperbole to say that the sci-fi action film profoundly changed … well, everything.

The Matrix influenced Hollywood, of course, but the movie's legacy extends far beyond the industry, touching the very fiber of what we think of as reality. The writer-directors didn't invent the idea that we're living in a simulation — others, such as sci-fi author Philip K. Dick, got there first — but The Matrix popularized the notion, helping to make it a movement. And like every other significant piece of pop culture, The Matrix also ended up being blamed for a lot of terrible things, including real-life shootings. In fact, it's fair to say that there's just about no aspect of society — entertainment, fashion, online culture, politics, the legal system — that hasn't been impacted by Lana and Lilly's magnum opus.

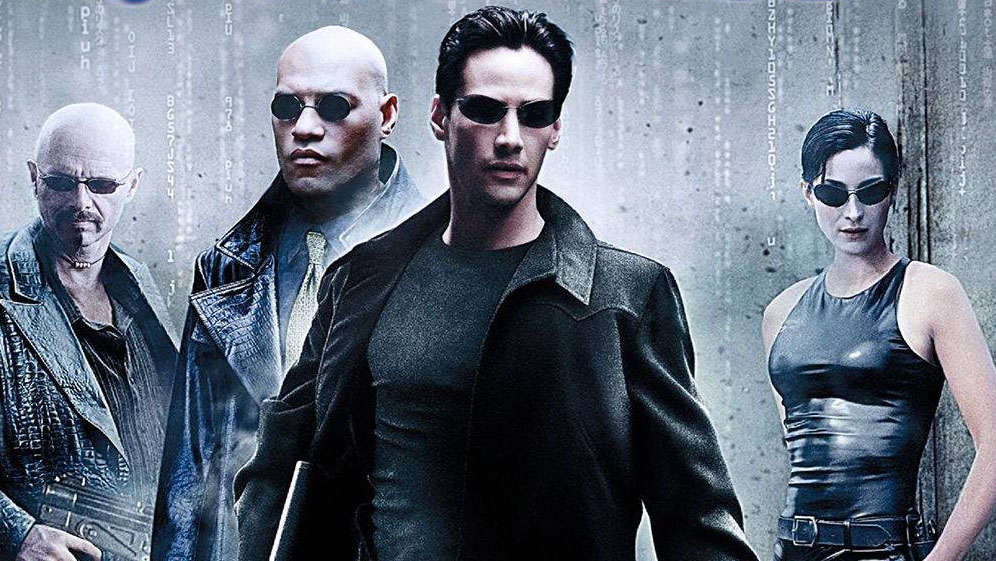

The Wachowskis crafted a classic hero's journey, giving it a pre-millennium jolt. In the film, Thomas Anderson (Keanu Reeves), an average-schmo hacker who goes by Neo online, is recruited by a man in sunglasses named Morpheus (Laurence Fishburne), who has shocking news for him: Humanity has been conquered by machines, which have created "The Matrix," a simulation of real life that keeps people blissfully unaware of the fact that they're actually slaves whose bodies are being harvested for fuel. After taking the red pill that reveals this horrifying reality, Neo joins Morpheus and Trinity (Carrie-Anne Moss) to bring down the machines. He is the one. He alone can free humanity.

The Matrix was only the second feature for the Wachowskis, who had previously written and directed the crime-thriller Bound, a stylish film but hardly indicative of the sci-fi blockbuster they were about to unleash. Four Oscars and nearly a half-billion dollars later, and The Matrix signaled a new way to think about event movies. In the process, the film cast a long shadow that the Wachowskis have struggled to escape ever since.

Why was it a big deal at the time? It was a franchise that started with a question: "What is the Matrix?" That query appeared in the 1999 Super Bowl commercial that teased the prospect of the forthcoming film — and it was the URL where intrigued viewers could log on to see what this strange movie was all about. In those initial TV spots and trailers, audiences got their first glimpse of the bullet-time technology that would be a game-changer, but the plot was kept under wraps. The marketing strategy was meant to make people wonder, well, what exactly was this mysterious Matrix?

The late 1990s were a period of high anxiety — was this Y2K thing real or just a hoax? — and the trepidation of entering a new millennium could be felt in that decade's movies, whether it was 1998's double-shot of asteroid-destroys-Earth dramas (Armageddon, Deep Impact) or in cyberpunk thrillers such as Johnny Mnemonic or Ghost in the Shell, which focused on a scary, dehumanized future. (And that's not even considering how epochal 1991's Terminator 2: Judgment Day had been in its imagining of a not-too-far-off time in which technology would enslave us.)

The Wachowskis synthesized these worries into one compelling package. In a statement that accompanied the release of The Matrix, the filmmakers said, "We began with the premise that every single thing we believe in today and every single physical item is actually a total fabrication created by an electronic universe."

This, too, was an idea already being felt in the culture: A year before the film's release, The Truman Show (a movie about a seemingly ordinary man who discovers he's the subject of a 24-hour-a-day reality show) was one of 1998's biggest hits, seizing on a universal fear that we can't trust what we see around us.

Lana and Lilly, who had worked in construction and written for Marvel Comics before making the leap to filmmaking, merged martial-arts action with the language of revolution and rebellion. (The movie ends with "Wake Up," from the fiery, politically-conscious rap-rock group Rage Against the Machine.) The Matrix was meant to engage the mind as well as dazzle the eye, and so the filmmakers found the best people to execute their vision, including Yuen Woo-ping, the legendary fight choreographer, who helped bring the balletic action scenes to life.

"The Wachowskis had been trying to get in touch with me for a while," Yuen told SYFY WIRE two years ago. "Eventually, they were able to find a Hong Kong producer who found me and told me about the project. I flew to America to meet them. I had so many questions, because at that time no one had seen a film like The Matrix. Nothing like it had been made in Hong Kong or America."

Such was the originality and daring of The Matrix that the filmmakers insisted their cast spend four months learning kung fu as part of their preparation. "The training was one of the things I had to consider," Reeves admitted at the time when asked about the challenges of signing up for the movie. "I said, 'I'm tired and I just want to do Chekhov.' And they said, 'You can do Chekhov when you're older.'"

Action movies weren't out of character for Reeves, who'd been a hit in Speed (and also starred in Johnny Mnemonic), but it took a while for Neo to be his. Everyone from Will Smith to Nicolas Cage to (remarkably) Speed co-star Sandra Bullock had been considered before Reeves came aboard, joined by Moss, Fishburne, and Hugo Weaving, who would portray the menacing, sardonic program Agent Smith. "At first I had reservations," Weaving recalled about signing on as the movie's principal villain, "but the more I read the script and as soon as I met [the filmmakers], I started to actually think the character was something that would be really fun to play."

Despite the hype around The Matrix, though, the year's biggest sci-fi extravaganza was sure to be the much-anticipated Star Wars: The Phantom Menace, the first installment in the George Lucas space opera in 16 years, which was due to open two months later. However, that spotlight being placed elsewhere only benefited The Matrix. Audiences went in wondering what the Matrix was — and they weren't prepared for what hit them.

What was the impact? The Matrix was the No. 1 movie in America for three of its first four weekends of release. Eight weeks into its run, when The Phantom Menace hit theaters, it was still the country's fourth-biggest movie. Buoyed by strong reviews and glowing word-of-mouth, the film quickly became a sensation, and even those who groused that the film's vision wasn't that original had to admit the Wachowskis had come up with something stirring.

Writing in the Los Angeles Times shortly after the movie's debut, journalist Eric Harrison noted, "Borrowing from everything from Greek myth to Alice in Wonderland, from the Bible to The Terminator (not to mention kung fu movies and comic books), The Matrix is so promiscuously allusive that it almost seems new." The Phantom Menace made more money — $924 million worldwide versus The Matrix's $464 million — but there was no question which film was cooler and in some ways more successful. Not to mention that The Matrix actually beat Phantom Menace for Best VFX at the 2000 Oscars.

Soon after, the filmmakers produced two blockbuster sequels, The Matrix Reloaded and The Matrix Revolutions, and laid claim to having masterminded the young century's most vibrant new franchise.

Everything about The Matrix became iconic. The characters' dark shades and black trench coats turned into the unofficial wardrobe for a lot of young fans. And Neo and his cohorts' sleek duds, which were meant to make them seem like superheroes, unconsciously anticipated the wave of comic-based movies to come. "They can move in an almost gravity-defying way. They can jump across buildings; they can almost fly," costume designer Kym Barrett said recently. "I wanted to find a modern version of something that could move like a cape, so that's where the coats were born."

For decades, sci-fi writers had speculated about alternate realities. (In 1977, Philip K. Dick gave a lecture in which he said, "We are living in a computer-programmed reality, and the only clue we have to it is when some variable is changed, and some alteration in our reality occurs.") And philosophers occasionally pondered the iffy certainty we had about the world around us.

"When I first read The Matrix," the Wachowskis' manager Lawrence Mattis once said, "I called them all excited because they'd written a script about [René] Descartes," a reference to the 17th-century thinker who famously declared, "If you would be a real seeker after truth, it is necessary that at least once in your life you doubt, as far as possible, all things." But after The Matrix, the notion that we might be living in a simulation grew in popularity — with entrepreneurs such as Elon Musk confidently espousing the theory in public. In fact, earlier this year, Room 237 documentarian Rodney Ascher released A Glitch in the Matrix, which explores the growing belief in simulation theory — as well as the advent of the so-called Matrix defense, a legal strategy used by defense attorneys claiming that their clients committed their terrible crimes because they didn't think they lived in the real world.

That wasn't the only negative effect of The Matrix, unfortunately. Shortly after the film's release, the Columbine shootings occurred, with the killers supposedly evoking Neo's trench-coated look. Later shootings were also blamed on the franchise, which featured bravura, prolonged shootouts that became an easy target for parental watchdogs and political conservatives. More recently, Neo's decision to take the red pill so that he can learn the truth about the Matrix has become an expression for misogynists expressing their toxic worldviews online: Getting red-pilled now means something far different than what the Wachowskis intended.

But the cultural reaction to The Matrix could also be quite cheering. Last year, Lilly (who, like Lana, is a transgender woman) acknowledged that Neo's journey was always meant to be a metaphor for being transgender. "That was the original intention but the world wasn't quite ready," Lilly said, later adding, "The Matrix stuff was all about the desire for transformation but it was all coming from a closeted point of view." As a result, the film has been inspirational to a community that doesn't often see their stories represented on screen.

"I love how meaningful those films are to trans people," Lilly said, "and the way they come up to me and say, 'These movies saved my life.'" If The Matrix has unwillingly been associated with hatred over the years, it's worth pointing out how much the movie has also inspired hope.

Has it held up? Not unlike Star Wars, The Matrix is now so ubiquitous in our society that it can be hard to appreciate it as just, y'know, a movie. There's so much baggage associated with the film that the cinematic innovation and astounding ideas are easily taken for granted. And yet, what endures is the pure kick of two up-and-coming filmmakers buzzing on their ingenious premise — and also the thrill of Reeves' performance as Neo, a regular guy who begins to grasp his grand destiny.

Plus, it's a really funny film, partly because of the script's quips and partly because of the endless cleverness of the world the Wachowskis conceived. Agent Smith is such a terrific villain — who doesn't do an impression of Weaving saying, "Misterrrrr Anderrrsonnn"? — and the story digs into the eternal pleasures of the hero's journey, encouraging us to cheer along with Neo's battle with the machines. It remains a first-class action film.

Maybe the sequels weren't quite as good. And maybe the Wachowskis haven't made a film since that's nearly as captivating. But it's hard not to get excited about the sequel, directed solely by Lana, that's headed our way at the end of the year. Neil Patrick Harris, who will be appearing in The Matrix 4, said recently, "I'm a big Lana Wachowski fan; I think she's a great person; I think she has a great inclusive energy. And her style has shifted visually from what she had done, to what she is currently doing. It's changed in an evolved way, and she's such a bright light."

Twenty-two years ago, she and Lilly shifted the whole way Hollywood thought about blockbusters. The Wachowskis failed to top The Matrix but, then again, nobody else could, either.

Tim Grierson is the co-host of The Grierson & Leitch Podcast, where he and Will Leitch review films old and new. Follow them on Twitter or visit their site. His new book, This Is How You Make a Movie, is out now.