Create a free profile to get unlimited access to exclusive videos, sweepstakes, and more!

The wild history of Walt Disney's animal obsession and the kingdom he built

Walt Disney liked to say that it all started with a mouse, but his affection extended to all animals. That deep affection has informed much of what the studio has produced over the last nine decades, from animated films to the invention of the nature documentary to an animal-filled theme park. This obsession with the natural world would ultimately culminate in this summer's The Lion King remake (now available on home video), which uncannily brought the African Sahara to life using cutting-edge digital technology. Even Simba's latest coronation, however, bears the influence of the founder's obsession with wildlife.

When Walt Disney was mounting his fifth animated feature, Bambi, he insisted the animators actually study animals. They couldn't be cartoony and shapeless, like they were in his early animated short films or in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, his groundbreaking, Oscar-winning original animated feature. (One animator compared those animals to "bags of flour.") For this new feature, Walt didn't want the animators relying on photographs — or worse yet their fuzzy memories — so he brought the animals to the animators.

"We found ourselves in a place where they had stacked with cages of all the animals that would be in the picture." Mel Shaw, Disney Legend and longtime animator, remembers on the special features for the Bambi home video release. In the same documentary, Joe Grant, who worked on character design and story for Bambi, remembered so many "live deer running around the studio."

They studied the animals meticulously, noting their physiology and the way their muscles moved. Those drawings would then be handed off to animators like Marc Davis, perhaps best remembered for his work at the Disney Parks (a new, two-volume collection of his work for those projects, co-authored by Up filmmaker Pete Docter, was just released and is incredible), who were tasked with giving these incredibly lifelike animals human expressions and relatable movements. "I was looking at a book of human psychology and every face is a human baby, interpreted onto the head of a deer," Davis recounted in that same documentary.

The results were breathtaking. The realistic animals, still emotive, sprung to life, especially when animated against Tyrus Wong's dreamily impressionistic watercolor backgrounds. Walt was widely regarded for his ability to "cast" animators for a certain project, and the animators he put on Bambi, including Milt Kahl and Frank Thomas, exceeded at every opportunity. Andreas Deja, a more recent Disney animator responsible for Gaston in Beauty and the Beast and the title character in Hercules, summed it up in the Bambi extras: "Walt wanted some poetry and some realism." And Walt got it.

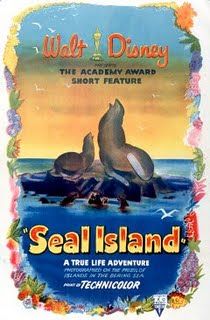

Inspired by his experience with the live animals on Bambi, Walt launched an ambitious project in 1948: the nature documentary. Already concerned with environmental conservation, his idea was to show animals and landscapes as they were, with the hopes that audiences, so captured with the images and stories, would fight to protect these natural wonders. Walt tasked a husband-and-wife team of photographers (Alfred and Elma Milotte) with traveling to Alaska and capturing footage of the "last frontier." Quickly Walt realized that the footage of seals was the most captivating aspect of the footage that was being returned and fashioned a film around it.

The resulting film, Seal Island, which Walt cannily labeled a "True-Life Adventure," made Disney's then-distributor RKO so nervous that it refused to release it. Walt took matters into his own hand, renting a theater in Pasadena so the movie could play (to packed audiences) for Academy Award consideration. When it took home the Oscar for Best Documentary, Walt told his brother Roy, "Here, Roy. Take this over to RKO and bang them over the head with it." (This according to the Walt Disney Family Museum.)

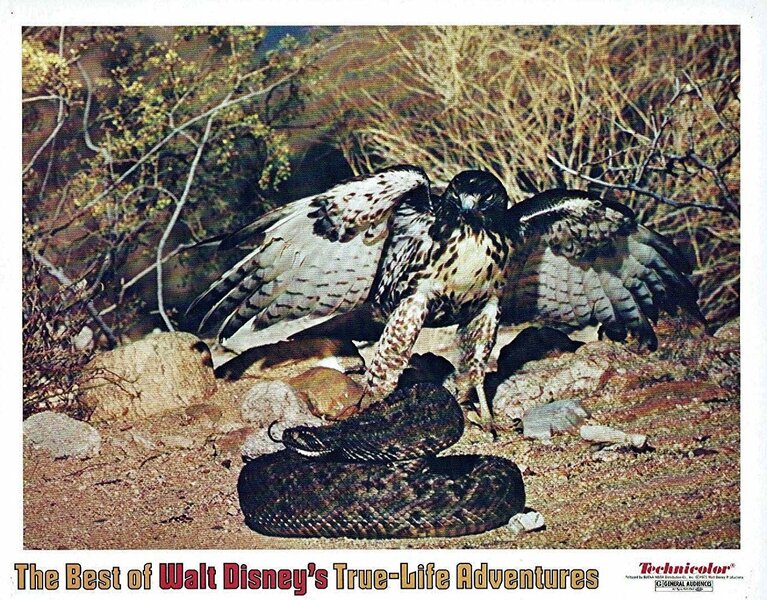

The series of films that followed in the True-Life Adventures series (dubbed "Walt's continuing chronicle of ecology") ended up winning eight Academy Awards. It inspired books and comic strips and were instrumental, for young audiences, in acclimating them with the wild world beyond their television or movie screen. Criticisms have been lobbed at the films over the years, for so-called staging of certain sequences, emphatic narration, and dramatic musical choices, but re-watching the footage now, those criticisms drop away.

The loosely framed "narrative" works and works well and the footage is genuinely wild, occasionally far scarier than anything that could be found in Walt's animated or live-action works. For instance, a wasp stings a tarantula to death while the narrator ponders how the wasp is going to drag the spider's corpse to a safe location. Damn, Walt.

And Walt strove for that realism again while putting together Disneyland, his next-level amusement park out amongst the orange groves in Anaheim, California. Various sections of the land served purely synergistic purposes — the castle was meant to prep visitors for Sleeping Beauty (which wouldn't end up opening until four years after Disneyland swung open its gates) and Frontierland felt very much inspired by the Disney-produced Davy Crockett miniseries starring Fess Parker.

For Adventureland, Walt wanted some of that True-Life Adventure spirit, so when brainstorming the Jungle Cruise, he had the idea to include real-life animals, to really give your river voyage a sense of danger. When this was deemed impractical, he came up with the idea to sell exotic animals in the attraction's accompanying gift shop. Can you imagine coming home from your family vacation to Disneyland with a python or Capuchin monkey? (Thankfully, this idea didn't get very far either.)

Walt Disney died in 1966, but his obsession with animals and conservatism carries on to this day.

In 1986, as part of the second phase of EPCOT Center, The Living Seas pavilion opened. At the time, it was home to the largest saltwater tank in the world (5.7 million gallons, later usurped by the massive Georgia Aquarium) and a number of aquatic animal species (including dolphins). Like Walt's original dream for the Jungle Cruise, it featured a somewhat fantastical storyline interwoven with your trip through the aquarium (you visited Sea Base Alpha, a futuristic research facility, and learned about the oceans).

Like the True-Life Adventures before it, it was a mixture of entertainment and education, meant to enlighten and expand awareness of guests who were probably just looking to get out of the Florida heat. In 2006 it was hastily re-themed with Finding Nemo characters but the core of the pavilion, and its emphasis on conservation, remained the same.

Two years after the Living Seas opened, an idea for a new animated feature began to germinate. It would be a spiritual successor to Bambi, only this time set in Africa. Originally titled King of the Jungle, The Lion King would formally enter development in 1990. During pre-production in late 1991, the filmmaking team went to Africa for two-and-a-half weeks. "It was the most amazing place I've ever been," recounted head of story Brenda Chapman on the home video special features.

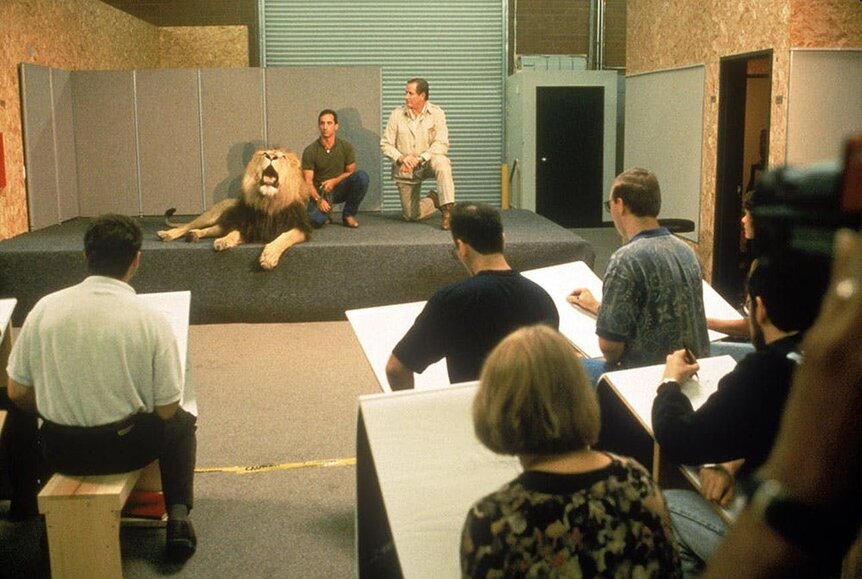

They saw predators and prey, side by side, hunting and being hunted. When the project finally reached the animation stage, nature documentaries were screened for the artists (including, undoubtedly, the 1955 True-Life Adventure The African Lion) and, just like with Bambi, live animals were again brought into the studio, accompanied by Jim Fowler, the noted zoologist and host of Mutual of Omaha's Wild Kingdom. Fowler brought a full-scale lion that looks a lot like Mufasa, as well as lion cubs that informed the design of young Simba.

The meticulous research that went into The Lion King led it a naturalistic feel that was far beyond what they had accomplished on Bambi. These animals moved and behaved in startlingly realistic ways that complimented the movie's unusually complex themes about life and death, the "Circle of Life" that we're all a part of. And the movie was a smash. At the time it was the most successful animated feature of all time and a watershed moment for the so-called Disney Renaissance, the creative rebirth that accompanied the arrival of Michael Eisner in a key leadership role at the company. The Lion King became the apex of that rebirth.

So it made sense that, when Eisner announced a new theme park for their Walt Disney World resort in Florida a year after The Lion King's release (almost to the day), it would be centered around animals. First announced as Disney's Wild Animal Kingdom, later shortened to just Disney's Animal Kingdom, it was a park that would feature live animals (including lions) but also animals from the distant past (dinosaurs) and, in a later expansion, mythical creatures as well (hence the dragon in the official Animal Kingdom logo).

"The imagination of Disney… gone wild" is how early commercials, accompanied by a blast of "Circle of Life," would describe the new park. And while some confusion followed (see their infamous "Nahtazu" advertising campaign), Disney's Animal Kingdom has blossomed into one of the most unique destinations in the Disney empire; Walt's original dream of conservation and entertainment that he was attempting in the True-Life Adventures and on projects like Jungle Cruise, writ large. Even while waiting in line for Flight of Passage, an immersive new attraction based on James Cameron's Avatar (in a parcel of land originally intended for the Beastly Kingdom expansion), you learn about the importance of "cornerstone" species in local environments.

In 2008, just before Earth Day, Disney announced something remarkable: they were embarking on an ambitious slate of documentaries in the mold of the True-Life Adventures. These new films, with their own label (Disneynature), would explore different animal species and environments and would carry over some of the filmmaking tenants that made the True-Life Adventures so successful, namely housing the films in a loose narrative, giving the animals character and audiences an emotional throughline.

African Cats is as much a story about family as anything else, and Chimpanzee is a coming-of-age story. Oftentimes these films would tackle somewhat bizarre subjects (Wings of Life is about the relationship between flowering plants and insects and it's one of the very best Disneynature films) and contain some startlingly fatalistic warnings about the precarious position the earth is in now. All of them are beautiful and involving and most have a chunk of their opening weekend grosses deferred to a conservationist cause associated with the movie's subject matter. And what's more — they keep making them. Penguins was released earlier this year and at least two more are coming, with Dolphin Reef (narrated by Natalie Portman) hitting the Disney+ streaming service sometime next year.

But the king of the jungle is still the king of the jungle and after 2016's astronomically successful The Jungle Book, Disney and that film's director, Jon Favreau, turned their attention to Pride Rock. And when the team finally embarked on this lavish, computer-generated remake of The Lion King, they headed straight to Disney's Animal Kingdom. This was a necessity since Rob Logato, the visual effects supervisor on the new Lion King, said that you can't really bring animals into your animation studio anymore.

"We can't bring an exotic animal and photograph it. I don't know if it's a Disney rule. It's sort of the #MeToo movement for animals," Logato explained to SYFY WIRE. Still, the alternative was preferred.

"We came to Animal Kingdom and were able to film them. But we weren't able to make them do things, like walk over from point A to point B. We just photographed and observed them," Logato said. This footage they used as a "guide." Since the production didn't want "exaggerated performances," they would often reference the footage they shot at Disney's Animal Kingdom. "It's here's what we did, why doesn't this look real?" Logato explained. And we look at the footage."

Jon Ross, from Disney's Animals in Film and TV program, said that he worked with getting the filmmakers "unprecedented access" to the animals at Animal Kingdom and that the production was at Animal Kingdom for about six weeks. "The idea being that they were really looking to film animals in a natural environment while minimizing the impact to the animals," he told SYFY WIRE. "The animals were living their-day-to-day lives and we just helped to get the filmmakers get as close as possible to the animals without impacting the animals' lives."

The Lion King team also referenced Bambi, with Walt's intentions for that film guiding the new production.

"We listened to the sweatbox, where Walt would be in this little room and go over everything with the animators. And they were trying to, even though it was animated, do realistic depictions of animals, not cartoon-y. So Bambi was an evolution. And we're going down that same path with what he wanted to do," Logato said. "We're just doing it with the technology that we have. The idea was that it was going to be photo-real and we believe that that's what he would have wanted to do if he'd had the technology to do it. We felt like we were doing the right thing."

Logato so believes in the accomplishment of The Lion King that he still refers to it as a live-action movie, not an animated film, even though none of it is actually live-action as we know it. "We were not making an animated movie. We were making a live-action movie. But we used animation tools to create it," Logato said. "If no one knew what we did, you would assume that we went to Africa and somehow got these animals to talk."

He said that animated movies look like Toy Story and that everybody knew Toy Story was an animated movie. But with The Lion King, the line is more blurry.

"It's an aesthetic label and the name belies what it looks like," Logato said.

And, true to form, the new Lion King offers an element of Walt's message of conservation and mindfulness. Claire Martin, who works with the Disney Conservation Fund (they've given out $86 million since the initiative was first developed), understands that getting the message out about the real-life animals is critically important. "

We know there is a huge awareness gap. We've lost half of the lions in Africa since the first film came out," she said. "When you have the opportunity to combine this great team of conservationists out there saving wildlife and tell those stories through an opportunity like The Lion King coming back again, it really gives us this unique chance to reach millions of people with the hopes of trying to inspire them to take action and join us." In other words: Walt would be proud.